This years iteration of the Ariadne@Brussels workshop series took place in Brussels EU Quarter from 8 to 10 December 2025. Researchers from the Ariadne project presented their latest findings on EU climate and energy policy and discussed them in an informal, focused setting with policy makers and stakeholders. The three days covered different thematic focuses, ranging from the integration of CDR in the EU ETS over to justice considerations of the net-zero transition to industrial policy and sector specific topics.

More than 200 participants attended the event both in person and online, representing national ministries of EU Member States, the European Commission and European Parliament, think tanks, consultancies, private businesses, business associations, and NGOs. Geographical representation among the registered participants was broad, with a strong presence from Belgium and Germany, alongside contributions from a wide range of other European countries including Poland, the Netherlands, France, Norway, the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain, Switzerland, Luxembourg and Romania.

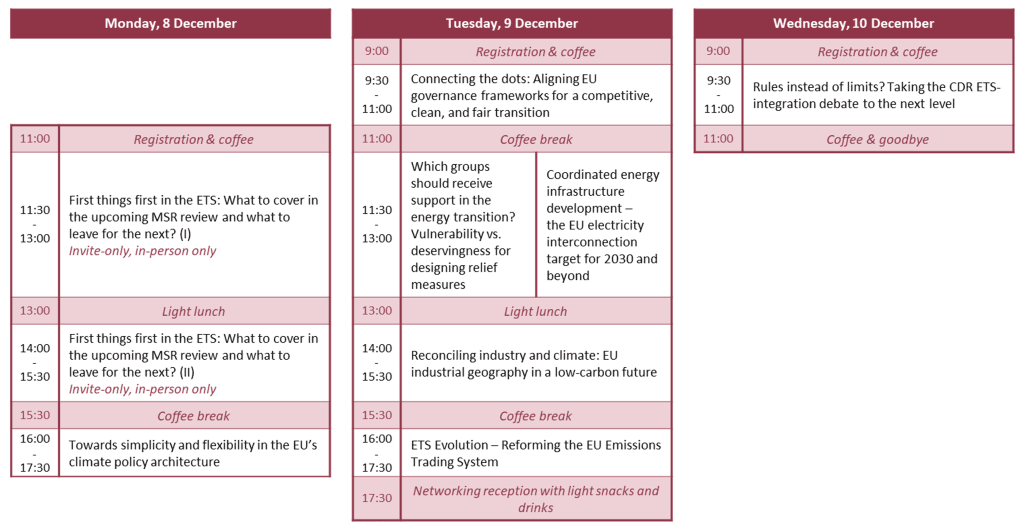

Agenda

Day 1:

First things first in the ETS: What to cover in the upcoming MSR review and what to leave for the next?

Any changes of the MSR rules following the 2026 review were expected to remain in place at least until the next review scheduled for 2031. A key challenge for the upcoming review was thus to anticipate how the market and its (in)stability would evolve in the coming five years. As things stood, a number of tipping points were looming over the further evolution of the ETS, including adjustments in the context of the 2040 target discussion and the Clean Industrial Deal, growing scarcity in the market and industrials increasingly dominating the market in terms of regulated emissions. Against this background, this workshop discussed two questions: (1) Could fundamental liquidity and volatility changes be expected for the next five years, what would drive them and could they endanger the functioning of the market? (2) Should potential major post-2030 reforms to the ETS (CDR integration, linking to ETS2, integration of international credits…) be left for the next MSR review when there was more clarity, or was it essential to prepare the long term through the short term and how so?

Speakers, interventions and inputs: Jos Delbeke (EUI/KU Leuven), Robert Jeszke (KOBiZE), Ottmar Edenhofer (PIK), Ingvild Sørhus (Veyt), Rosy Finlayson (BloombergNEF), Julien Mazzacurati (ESMA), Gabin Mantulet (Enerdata), Sebastian Lizak (KOBiZE), Yan Qin (ClearBlue Markets), Benjamin Görlach (Agora Energiewende); Michael Pahle (PIK – moderation)

Key takeaways from the organisers: The 2026 review of the EU ETS is casting its shadow on the operation of the EU carbon market. Several elements under review will strongly affect the operation of the carbon market, and the resulting carbon price: The Market Stability Reserve, a re-calibration of the Linear Reduction Factor towards the new 2040 target, and the inclusion of negative emissions into the ETS. All of this happens against a backdrop of heightened political and economic uncertainty and an increasingly tight carbon market. A key challenge for the upcoming review is thus to anticipate how the market and its (in)stability will evolve in the coming five years, what expectations market participants will form, and how they may adjust their strategies.

For the fifth time running, the Ariande Project convened academic researchers and carbon market analysts to compare their expectations of EU ETS prices going forward. The expected prices range from €140-200/t by 2030, and thus in a similar range as in previous years. Fundamentals alone would suggest higher values, but political uncertainty dampens the outlook: the risk of a rollback dampens price expectations and may lead some market participants into a more attentive stance.

To maintain a stable market in the coming years, options from technical adjustments to structural reforms were discussed. Any such reform must be technically robust, politically durable and credible for market participants. One such option would be a price corridor to anchor expectations and provide a clearer signal to industry, yet legal feasibility remain uncertain, and the challenging political climate might yield a corridor significantly below what would be needed to send the right signals to emitters and investors.

Towards simplicity and flexibility in the EU’s climate policy architecture

In its proposal to amend the EU climate neutrality framework, the Commission stated that for designing the policy architecture beyond 2030, “it will examine how simplification and flexibilities across sectors could facilitate the achievement of the 2040 target”. Simplicity was essential to lower transaction cost and fostered investment for the low-carbon transition. Flexibilities could allow a more efficient allocation of scarce resources (land, labour, capital) across sectors, technologies and time in order to keep overall cost of achieving net-zero modest. Within this workshop we discussed how simplification and flexibilities could be used without risking a watering down of targets and ambition.

The starting point for discussion was the proposed post-2030 architecture, specifically its use of flexibility mechanisms under the Paris Agreement (Art. 6 mechanisms) and the effect of EU climate targets on Member States. The premise was thereby an overall credible new architecture to incentivize efficient investments; key to that was a controlled convergence approach of its various compliance systems (ETS, ESR, LULUCF regulation). An important ramification could be to develop the ETS an open system (“hub”) going forward and establish regulatory docking points to link-up CDR, international credits and the LULUCF sector already in the next round of reforms.

Speakers and interventions: Markus Ehrmann (Stiftung Umweltenergierecht), Georg Zachmann (Bruegel), Ottmar Edenhofer (PIK)

Key takeaways from the organisers: Markus Ehrmann started the session with a legal assessment of the EU’s 2040 target provisions. He emphasized that these provisions not only assign the Commission with the task to review the whole EU’s legal climate architecture in order to enable the achievement of the target. In addition to that, the regulation of the target itself requires further legal provisions (e.g. defining the criteria for the contribution of international credits under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement). Georg Zachmann followed by highlighting the current fragmentation between different compliance mechanisms in the architecture, arguing that arbitrage opportunities would inevitably lead to convergence in the system. He suggested a more pragmatic approach, proposing that the EU should harness simplicity and flexibility as policy design principles. As a consequence, the EU should see the EU Emissions Trading System as the host system with a “gold standard” of emissions allowances, to which further compliance mechanism in the architecture could be gradually linked. This approach would deliver a unified and coherent target architecture in the very long run. In his reaction, Ottmar Edenhofer stressed that any design of the future policy architecture must uphold the EU’s integrity in its climate ambition. Against this background, he warned that the term “flexibility” tends to be used with the aim of watering down ambition through the back door. Edenhofer also underscored that – given current political feasibilities – fragmentation will continue to play a role, and that hence a right balance between convergence and fragmentation needs to be found such that policy commitment can be maximised. The following discussion turned to broader issues of fragmentation, noting not only the fragmentation in compliance mechanisms but also the lack of coordination in support instruments, such as sector-specific subsidies. A suggestion was made to quantify the inefficiencies caused by this fragmentation, with an emphasis on projecting how these inefficiencies might evolve over time.

Day 2:

Connecting the dots: Aligning EU governance frameworks for a competitive, clean, and fair transition

As the EU pivoted toward competitiveness as its defining priority for the foreseeable future, questions arose about whether existing and planned economic governance tools aligned with those for decarbonisation and a just transition. How did we know if we were on track towards an EU economy that was at once competitive, clean, and fair? How integrated were the accountability frameworks for these three interlinked priorities—on paper and in practice? What options existed to improve connections and streamline processes for a cohesive approach?

This session explored the preliminary findings of a new study that mapped the various governance frameworks underpinning these three aspects of the EU’s 2050 transition, including national planning and reporting under the Governance Regulation, Social Climate Fund, and European Semester as well as new tools at EU level and the proposed National Regional and Partnership Plans under the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). The study examined where integration worked, where it fell short, and how future EU architecture could better link accountability and monitoring, ensure effective feedback, and deliver on the European Commission’s promise of a ‘simpler, faster Europe.’

Speakers and interventions: Corinna Fürst (Ecologic Institute), Michael Forte (E3G), Koen Meeus (Belgian Federal Climate Change Department), Frank Siebern-Thomas (European Commission, DG EMPL); Matthias Duwe (Ecologic Institute – moderation)

Key takeaways from the organisers: With its Clean Industrial Deal, the EU is focusing on competitiveness as a policy priority for the foreseeable future. This session explored whether existing and planned new governance tools such as the Competitiveness Coordination Tool and the Annual Single Market and Competitiveness Report align with governance frameworks for decarbonization and a just transition. Corinna Fürst (Ecologic Institute) opened the session with an analysis of the governance frameworks. She noted that integration of governance mechanisms has improved over the years and conditionality as a mechanism was established with the Recovery and Resilience Plans. The proposed National and Regional Partnership Plans under the next Multiannual Financial Framework are foreseen to follow this approach by introducing a performance-based system. This has the potential to improve not only integration across policy areas but also national policy by making access to EU funding contingent on adequate implementation. Regarding the underlying data which is used in monitoring and reporting exercises by both the EU and Member States, better integration is required. Instead of a fragmented approach a common indicator base combining climate, economic and social policy could improve more integrated policy making. Misalignment of timing and sequencing currently hampers the integration of policy planning cycles. Particularly important would be to ensure that policy plans are developed ahead of funding plans.

The panel discussion with Frank Siebern-Thomas (DG EMPL), Michael Forte (E3G) and Koen Meeus (Belgian Federal Climate Change Department) highlighted that especially for the just transition a better evidence base is required. It was also noted that non-alignment across governance frameworks can hamper sending consistent signals to the private sector regarding the direction of travel of European policy. Misalignment is particularly visible with regards to public investment. Fiscal frameworks might come into conflict with the long-term objectives of climate and social policy plans.

Coordinated energy infrastructure development – the EU electricity interconnection target for 2030 and beyond

The development of appropriate infrastructure is the basis for a functioning internal electricity market within the EU. Hence, the European Council in 2014 called for the EU Member States to pursue an interconnection target of 10 % until 2020 and 15 % to 2030. Today, the EU Governance Regulation lists this target as one of the “Union’s 2030 targets for energy and climate”, Art. 2(11) Regulation 1999/2018/EU. The European Commission announced a proposal for a European Grids Package for the beginning of 2026.

Against this background, this workshop was intended to present our research on the legal nature and content of the interconnection target, i.e. explore who was obligated to do what. We then looked at the impact of the 15 %-target for 2030 on the energy system and the EU’s climate protection ambitions, and examined scenarios for the time beyond 2030. A panel of experts was invited to share their views and discuss with us. Some time was scheduled for questions from the audience.

Speakers and interventions: Jana Nysten (Stiftung Umweltenergierecht), Peiwen Zhang (IER), Catharina Sikow-Magny (European University Institute), Christoph Maurer (Consentec), Thomas Dederichs (Amprion); Markus Blesl (IER – moderation)

Key takeaways from the organisers: The discussion focused on the challenges and future needs of EU-level interconnection planning and energy infrastructure development. While the EU’s interconnection targets may have great symbolic value and show a strong commitment to create the infrastructure for the EU internal energy market, a uniform interconnection target cannot adequately address the diverse conditions and priorities of Member States. Strengthening alignment between national development plans and EU frameworks is therefore essential. To improve coordination, Member States should provide robust scenarios, cost data, and demand projections, enabling EU-level planning to better reflect national realities. Multiple planning scenarios are necessary to address long-term uncertainties, including significant national differences such as variations in renewable full-load hours, which directly affect investment outcomes. Furthermore, a major challenge lies not in planning itself but in project implementation. EU-level projects are often hindered because costs and benefits are unevenly distributed, and cross-border cost allocation mechanisms remain ineffective. Countries may resist funding projects that primarily benefit their neighbors. Strengthened regional cooperation is critical to overcoming political, technical, and stakeholder barriers. Storages will play an increasingly important role in enhancing system flexibility, and early, coordinated EU-level strategies are essential, given that infrastructure development typically spans more than a decade. Cost-benefit analyses must carefully account for national differences, and financial instruments beyond grants are needed to maintain the right incentives and prevent unnecessary investments. Last but not least, inadequate investment in interconnections results from misalignment between national and EU priorities. Achieving a flexible, resilient, and sustainable European energy infrastructure requires stronger coordination, efficient financing, and accelerated project implementation.

Which groups should receive support in the energy transition? Vulnerability vs. Deservingness for Designing Relief Measures

The energy transition is creating new social realities and divides: while some groups benefit, others experience the process as unfair because burdens and benefits are distributed unequally. Policymakers have largely focused on identifying vulnerable groups – based on income or energy poverty indicators – and compensating them accordingly. Yet fairness perceptions depend not only on objective need but also on deservingness: judgments about who should receive support based on responsibility for causing emissions and capacity to adjust. The session discussed the ability of the Social Climate Fund (SCF) to address vulnerability and generate acceptability, and how integrating deservingness considerations could improve the design of the SCFs.

Speakers and interventions: Simon Feindt (PIK), Giulia Colafrancesco (ECCO Institute), Alessia Fulvimari (DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Jacob Edenhofer (University of Oxford); Michael Pahle (PIK – moderation)

Key takeaways from the organisers:

1. Country-level perspective

At national level, defining vulnerability remains contested. Many countries still rely on income based criteria, overlooking regional disparities and middle income households also exposed to transition risks. Limited SCF funding cannot alone build public support but can motivate institutional reforms and targeted measures. Ensuring procedural fairness through (public) evaluation are crucial to make national mechanisms credible and inclusive, and improve the accuracy of the SCF.

2. EU-level perspective

At EU level, carbon pricing remains a central to achieving climate neutrality, and the SCF a key tool to enhance its acceptability by supporting those least able to adapt. However, its scale and duration remain modest, and uneven administrative capacities hinder achieving a just transition. Continuous evaluation, close coordination with Member States, and dialogue with the public are needed to improve accuracy and fairness. The implementation of the SCF already shapes new interest groups and contributes to a wider political debate about fairness in Europe’s transition to carbon neutrality.

3. Deservingness and acceptability

Moving from vulnerability to deservingness may help policymakers align normative aims with political feasibility. Yet, deservingness can draw on distinct logics—responsibility based and constraint based—that may not always overlap. Dilemmas arise when electorates diverge in their judgments of whose losses are legitimate or who deserves compensation. Policies that “unbundle the blame”—separating carbon intensive firms from their workers—can, under certain conditions, foster new coalitions across otherwise divided electorates (for example, between core green voters and workers in high emission sectors). Conditions to achieve this “unbundling” are narrow, as it might require credible messengers and careful acknowledgment of perceptions and emotions of individuals and societal groups in the transition.

Reconciling industry and climate: EU industrial geography in a low-carbon future

Despite an ambitious vision in the Clean Industrial Deal, the transformation of the EU’s industrial base toward a low-carbon future had yet to take off. The combined pressures of the energy crisis and geopolitical tensions had placed energy-intensive industries—such as steel, chemicals, and cement—under severe strain. Faced with rising costs and competitive pressures, some sectors had begun to push back against the EU’s climate architecture as being too ambitious. The result was a climate investment landscape marked by uncertainty. Volatile carbon prices, slow progress in scaling key technologies like green hydrogen, and delayed infrastructure investments—particularly in pipelines and grids—had dampened confidence in the transition even further. As Europe sought to reconcile its industrial competitiveness with its decarbonisation commitments, questions arose about the geography and governance of its industrial future.

Against this background, this session aimed to discuss the regional and sectoral futures that were emerging as the EU’s low-carbon transition took shape. How could the EU’s climate policy framework give “breathing room” to its industry without undermining the credibility and predictability required for investment? How might the market structure/geography change – status quo, strong renewable pull, or more diversified supply chain (e.g. green iron in one country, steel production in another)? And lastly, how could and should the EU support diversification, also considering state aid rules and the internal market?

Speakers and interventions: Darius Sultani (PIK – input and moderation), Ysanne Choksey (Agora Industry), Ben McWilliams (Bruegel), Francesca Payne (Salzgitter AG)

Key takeaways from the organisers: In his impulse presentation, Darius Sultani (PIK) posed four main challenges for the low-carbon transition of EU industry: (i) Identifying and addressing bottlenecks in expanding low-carbon capacity, (ii) finding “sweet spots” to split value chains such that they balance cost-effectiveness and resilience, (iii) the coordination problem in scaling up low-carbon infrastructure, and (iv) giving industry “breathing room” to transition without undermining policy credibility. All of these challenges need to be set within the context of the upcoming EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) revision, which is expected to crystallize all these issues at once.

During the interventions, it was emphasized that clear and stable policy momentum is essential to make deep-decarbonizing projects a reality. For steel specifically, taken trade measures, the Industrial Accelerator Act and the reform of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism were welcomed. However, significant uncertainties remain, notably around climate policy ambition in the coming years and the role of hydrogen for decarbonising EU steel. It was therefore pointed out that, after an initial wave of hydrogen-based direct reduction iron (H2-DRI) projects already underway in the EU, a second wave will likely rely on imports of intermediate products (specifically hot-briquetted iron).

The following discussion delved into broader issues such as the challenges of building future value chains amidst global trade uncertainty. The question was raised whether observations from other sectors could be used to learn for the EU’s industrial geography of energy-intensive industry. Specifically, participants drew parallels to the battery and electric vehicle sectors, with initial investments directed towards Spain and Hungary. In addition, there was debate about whether the EU should focus on creating a resilient ecosystem within its single market and with close partners, rather than relying on global trade dynamics. At the same time, the potential for a new industrial geography within the EU could offer compensation for states that lose out on fossil fuel-related revenues, presenting opportunities for international climate diplomacy.

ETS Evolution – Reforming the EU Emissions Trading System

Due to the finite number of emissions allowances, the EU emissions trading system (EU ETS) was facing an end game situation. Several reforms had been proposed and were being discussed to prepare the EU ETS for a time when no new emissions allowances would be issued, including but not limited to the inclusion of new sectors or new types of allowances. With the EU ETS being a climate protection measures, and thus adopted and reformed based on the EU’s respective competence under Art. 192 AEUV, some concerns existed as regards the right legislative procedure for respective reforms. So far, Art. 192(1) AEUV and the ordinary legislative procedure (with majority voting in the European Parliament and the Council) was used. However, for reforms “primarily of fiscal nature” and those that significantly impact the Member States’ energy sovereignty, the special legislative procedure with unanimity in the Council is prescribed. Certainly, thus, any reform of the EU ETS would require the political will of the EU legislator.

This session was intended for scientists and policymakers, as well as other stakeholders, interested in the development of the EU ETS. It included a presentation on the legal basis for a(ny) reform of the EU ETS, and featured a discussion of both the legal and political aspects of such reform.

Speakers and interventions: Jana Nysten (Stiftung Umweltenergierecht); Michael Pahle (PIK – moderation)

Key takeaways from the organisers: A(ny) reform of the ETS Directive will have to be based on a provision in the Treaties that gives the EU the respective competence; the procedure set out in that provision will need to be followed. While so far the ETS Directive has been based on Art. 191(1) TFEU, Jana Nysten (SUER) presented the conditions under which Art. 192(2) TFEU would require a special legislative procedure. The ensuing discussion focused on potential changes to the ETS Directive and whether they would make it a “provision primarily of a fiscal nature” (Art. 192(2) subpar. 1 lit. a) TFEU) or one that significantly affects a Member State’s energy sovereignty (Art. 192(2) subpar. 1 lit. c) TFEU). Michael Pahle (PIK) in this context explained the “ETS endgame”; other issues raised included taking revenue from the auctioning of the emissions allowances for the EU budget, changes to the market stability reserve and the inclusion of carbon dioxide removal (CDR). Overall, the exchange showed that in order for the ETS evolution to run smoothly, careful preparation of (proposals for) legislative reform is key.

Day 3:

Rules instead of limits? Taking the CDR ETS-integration debate to the next level

The gradual integration of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) into the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) was widely seen as a crucial step toward achieving long-term climate objectives. At the same time, there remained large uncertainty in terms of cost, quantities and quality CDR suppliers could provide. Separate CDR targets or limits had consequently been proposed to accelerate deployment while avoiding strategic abatement delays or environmental risks that could undermine policy credibility. However, it was questionable whether strict volume limits were suitable to address potential policy and market failures associated with a CDR integration. In addition, questions remained on how to put them into practice, i.e. on the “why” and “how” behind target design and their evolution over time.

With this session, we argued that – to take the CDR integration debate to the next level – a shift was required from fixed volume limits toward clearly defined rules. Two key questions were being addressed: How could a credible CDR integration and scale-up rules be designed that ensure a robust, future-proof carbon market? What was the underlying logic behind these rule, i.e. what objectives should they serve? To this end, the session explored the purpose, design logic, and dynamic evolution of CDR integration rules and support instruments within the context of the EU ETS. It examined how they could be structured to unlock learning, safeguard abatement incentives, address environmental concerns, and create a credible pathway for CDR integration.

Speakers, interventions and discussants: Bjarne Steffen (ETH Zurich), Flore Verbist (PIK / KU Leuven), Darius Sultani (PIK – input and moderation), Michael Pahle (PIK), Malgosia Rybak (CEPI), Francesca Battersby (Carbon Gap), Martin Birk Rasmussen (Concito)

Key takeaways from the organisers: This year’s Ariadne@Brussels session on Carbon Dioxide Removals (CDR) explored how removals can be integrated into the EU ETS amid persistent uncertainties. Bjarne Steffen (ETH Zurich) opened by emphasizing the crucial role of compliance markets in providing revenues and bankability for CDR firms. He noted that most business models require stacked revenues – combining subsidies with compliance market income – and that the cost gap for DACCS remains substantial, with new generations unlikely to change these fundamentals for the time being. In the following presentation, Flore Verbist (PIK/KU Leuven/VITO) stressed upon the uncertainties regarding these permanent CDR costs and availabilities, which complicates the process of predetermining future CDR and hard-to-abate emissions in the EU ETS. A rule-based CDR integration corridor was proposed to strengthen the credibility of a sequencing path for CDR into the EU ETS, creating more volume flexibility allowing to balance abatement deterrence and cost-ineffectiveness risks. The following intervention highlighted that unclear policy signals currently hamper investment for those industrial players who could potentially provide CDR supply if incentives are set accordingly. Given the latest changes to the EU’s 2040 target, several known unknowns remain, including CDR methodologies, the role of the Market Stability Reserve, and the use of international credits inside and outside the ETS. Throughout the interventions, it was argued that predictability is essential for CDR firms, making corridor width a central design question going forward. More clarity is also needed in terms of clear criteria and data for defining the corridor, as well as on the question whether policymakers should steer towards the corridor’s maximum or minimum. However, since the ETS would form only one part of firms’ revenue stack and are insufficient to scale CDR, it was pointed out that CDR policy must extend beyond the ETS. In the discussion, participants stressed the importance of making room for innovation within the corridor while safeguarding environmental integrity. Because unknown unknowns are inevitable, some elements of a “shock-proof” system may need rule-based management while others allow discretion. Key open questions included how to treat subsidies inside or outside the ETS, how to adjust and enforce the corridor (especially its minimum), what numerical values it should contain, and how the proposal connects with CDR needs and policies beyond the ETS.