Table of Contents

Key messages

- Previous research on the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has focused on the design and international impacts and reactions. This study looks inward. It unpacks how the EU’s institutions organised their diplomatic outreach regarding the CBAM internally.

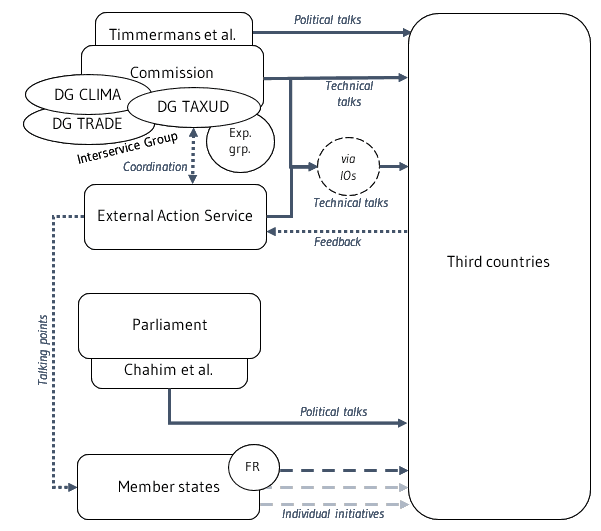

- The political focus during the examined period was on negotiating the CBAM between the member states. Parallel diplomatic activities were secondary and coordinated only to a limited extent, both among the EU institutions and between the EU institutions and the member states. CBAM diplomacy did not fulfil the hope for a more strategic approach to the EU’s international climate policy.

- The political leadership of the Commission and individual members of the European Parliament drove the negotiation process forward within the EU and held political talks with partner countries. The Commission’s Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union was in the lead internally. It and the External Action Service endeavoured to counteract the perception of the CBAM as a trade policy instrument and to ensure a certain degree of coherence in diplomatic outreach.

- In terms of substance, the focus of CBAM diplomacy was on explaining the technical modalities of the mechanism. Instead of approaching partner countries with concrete concessions, these modalities were portrayed to the outside world as unmalleable, while the details were still being negotiated internally among the member states.

- Nonetheless, after some strong initial international reactions, excluding the political dimension of the CBAM in talks with partner countries that has – at least so far – proven to be effective in overcoming some of the resistance.

1. Introduction

Starting in 2026, a carbon border adjustment is due in the European Union when goods are imported whose production in a third country is not subject to climate mitigation measures comparable to the EU’s emissions trading system. This is intended to prevent EU climate action from being circumvented and the European economy from suffering undue competitive disadvantage from its decarbonisation efforts vis-à-vis less ambitious countries. It was clear from the outset that such a comprehensive unilateral project would not necessarily be met with approval in many third countries, given the economic, trade, and climate policy implications (Bellora & Fontagné, 2022; Dröge, 2021; Eicke et al., 2021; Kolev et al., 2021; Sapir & Horn, 2020). The proposed introduction of a similar mechanism for international air traffic in 2012 had already triggered a debate on trade law (Meltzer, 2012). How the EU’s trading partners would perceive the new carbon border adjustment was therefore essential for its political acceptance and effective climate cooperation going forward. Apt diplomatic action was warranted. The existing literature focuses on the design of the mechanism (Campolmi et al., 2024; Cosbey et al., 2021; Dröge, 2021; Espa et al., 2022; Mehling et al., 2019; Mehling & Ritz, 2023; Sator et al., 2022). Some works also examine the diplomatic exchange with partner countries required to take the expected effects and reactions into account (Dröge, 2021; Jakob, 2023; Mehling et al., 2022; Szulecki et al., 2022). The question of how these diplomatic efforts were implemented internally, however, is understudied. How did the European Union organise diplomacy around its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism? “[I]n order to understand the EU’s external action, we must also look at its internal bureaucratic politics” (Delreux & Earsom, 2023). This paper looks inward. In an exploratory analysis based on expert interviews, it addresses the question of how the EU’s key institutions understood their diplomatic role with regard to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Which EU institutions communicated with third countries? What channels did they use? Who was taking the lead, and how did the institutions involved coordinate between each other?

2. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

Initially proposed by the European Commission in late 2019, the EU’s Green Deal is a strategy that aims to combine ambitious and comprehensive climate action with social cushioning for those affected by structural change as well as climate-compatible wealth and prosperity (European Commission, 2024; Fetting, 2020). The plan for implementing this strategy took shape in July 2021 when the European Climate Law came into force and the Fit-for-55 package was drafted (Europäische Union, 2021; European Parliament, o. J.). The European Union aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels, and achieve climate neutrality by 2050. A key component of this is the expansion of the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) to previously excluded sectors of the economy. The free allocation of certificates for internationally competing, greenhouse gas-intensive industries is to be phased out by the beginning of the 2030s (Pahle et al., 2023). This extended emissions pricing, however, risks that cheaper, more climate-damaging substitute imports from third countries – such as cement – will negate any emission reduction effects (carbon leakage). Imports from specific groups of goods are therefore to be subject to a levy that compensates for the lack of carbon pricing in the country of origin. A side benefit of this Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is that it would mitigate competitive disadvantages for the European economy vis-à-vis non-cooperative countries with unpriced carbon emissions, cushioning the risks faced by industries in ambitious countries (level playing field). After all, while the EU’s climate action will gain in ambition with the expiration of the free allocation of emission allowances, the EU loses a key instrument for accompanying economic policy. Furthermore, the prospect of conditional exemptions from the CBAM offers an economic incentive for the EU’s trading partners to take more ambitious climate protection measures. This way, the CBAM can also have an impact on climate policy beyond the borders of the EU.

2.1 History

Carbon border adjustment is generally not a new idea (Barrett & Stavins, 2003; Dröge, 2011; Grubb, 2011; Ismer & Neuhoff, 2007; van Asselt & Brewer, 2010; Wooders et al., 2009). Concrete initiatives for implementation in the European Union, however, were initially met with little approval. Two years after the EU ETS was introduced in 2005, the Commission presented a first informal proposal for a border adjustment as part of the reform for the third trading period (2013–2020) (Leturcq, 2022; Mehling et al., 2019). In 2009, France submitted its own informal proposal for a border adjustment. Another informal proposal was submitted in 2016, again by France, for the cement sector and taken up by the European Parliament. This proposal received a positive vote in the Environment Committee (ENVI), but it was rejected in the plenary (ibid.).

In July 2021, the EU Commission presented a proposal for the introduction of the CBAM as part of the Fit-for-55 package. Once again with the initiative from France as part of its Council presidency, the Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) reached agreement on a general approach to the CBAM regulation in March 2022. Member states’ positions at the time ranged from support for the CBAM to general acceptance to rejection of the general approach by Poland (Council of the European Union, 2022). In September 2021, the Parliament’s Environment Committee adopted the CBAM proposal. MEP Mohammed Chahim (S&D, Netherlands) was appointed CBAM rapporteur. The plenary voted on its position on the CBAM legislative proposal in June 2022. In October, the first meeting of the informal CBAM expert group took place, in which third countries participated as observers. This informal expert group supports the Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union (DG TAXUD) in finalising the methodologies for reporting, quantification and verification of embedded emissions from products in the CBAM sectors and in the early preparation of implementing acts (European Commission, 2022).

Negotiations between the Council and the Parliament began in July 2022 and concluded with a provisional agreement in December 2022. Deliberations on the proposal took place in the ad-hoc Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism group set up by the Council (Council of the European Union, 2022). With its adoption in the European Parliament in April 2023 (European Parliament, 2023), the CBAM is now being implemented. In the transitional phase, which began in October 2023 and runs until the end of 2025, importers will initially only have to report on imports from selected product groups without any actual adjustment payments due (Healy et al., 2023). The CBAM is scheduled to fully enter into force in 2026 and will be introduced gradually, while the free allocation of emission allowances will be reduced annually and will finally expire in 2034 (Europäische Union, 2023b, 2023a).

2.2 International reactions

The EU ETS and the CBAM illustrate how the EU’s market-based climate policy can have an impact internationally (Leonard et al., 2021; Oberthür & Dupont, 2021). While the interlinkages between the policy fields of economy, trade and climate offer opportunities for strategic cross-links (Delreux & Earsom, 2023), they also pose challenges for any accompanying diplomatic efforts. Third countries raised concerns about the CBAM in light of the potential economic impact on trading partners, the legality under international trade law and possible retaliatory measures, as well as the implications for climate policy and development that can result from its practical implementation.

Compatibility with WTO rules was a key concern from the beginning (Espa et al., 2022; Porterfield, 2023). The CBAM might be perceived by trading partners as a protectionist measure – a tariff protecting European industry (Brandi, 2021; interviews 1, 10, 13). Consequently, there was a danger that countries would react strongly – especially those that have the resources to introduce import tariffs to retaliate against trade disadvantages or challenge the European Union before the WTO (Dokk Smith et al., 2023). In China and South Korea, observers warned emphatically of an outright trade war (Gläser & Caspar, 2021; Lee, 2021; Lim et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2023; Zhong & Pei, 2022) “The world economy will inevitably face a vicious cycle of trade retaliation.” (Lim et al., 2021) In line with its usual strategy in climate negotiations (Christoff, 2010; Eckersley, 2020; LMDC, 2013; Xinhua, 2023), China insisted on the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities. The EU countered this by arguing that the CBAM does not differentiate between countries, but applies at industry level (interview 10). In addition, a number of aspects of the CBAM are designed to make the introduction as smooth as possible for trading partners, such as the two-year transition phase during which no levies are due (interview 2). The US expectedly expressed initial reservations about the CBAM (Hook, 2001; Øverland & Sabyrbekov, 2022). Later, however, coinciding with the Inflation Reduction Act, there have been various bipartisan initiatives for possible cooperation with the EU, motivated partly by climate and partly by trade concerns (Chahim, 2022; de Jong, 2022; Gangotra et al., 2023; Siegel, 2022). With countries such as Canada, which already has a carbon pricing system, talks were generally straightforward (interview 10).

The discussions around the economic implications of the CBAM were especially charged when it comes to developing countries and emerging economies. Countries whose exports consist to a large extent of relevant industrial goods such as cement, aluminium, steel, or fertiliser are particularly exposed to the trade effects of the CBAM (African Climate Foundation & Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa, 2023; Eicke et al., 2021; Heli, 2021; Magacho et al., 2023, 2023; Sharma & Gupta, 2022). This applies to Mozambique and Moldova, for example (Magacho et al., 2023). Exemptions are given to trading partners with comparable carbon pricing systems. However, introducing such a system is difficult for many developing countries in view of the political-economy implications and the required institutional capacities (Price, 2020). In addition, granting exemptions from the CBAM comes close to a general idea of a Nordhaus-style climate club, in the sense that cooperative countries are granted advantages if they meet certain conditions (Farrokhi & Lashkaripour, 2022; Nordhaus, 2015; Szulecki et al., 2022).1This assessment is not shared by the EU, as the CBAM does not differentiate by country, but by product type (interview 2). It is precisely this aspect that many countries in the Global South perceive as contradictory to the principles of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement. By granting exemptions from the CBAM, the EU would effectively decide whether the climate policy of other countries is adequate (Gläser & Caspar, 2021; South African Government, 2021). Another issue that was controversial concerned the suggested use of the revenues from the border adjustment. Spending it on capacity building and climate finance in partner countries could provide further incentives to comply with the CBAM. This could help ease pushback (Øverland & Sabyrbekov, 2022). However, conditionality is a long-standing issue in international climate finance, i.e. the extent to which it is morally appropriate and politically prudent for industrialised countries, which have contributed significantly to global climate change, to subject the urgently needed financial support for climate action in developing countries to prior conditions, such as in this case the successful implementation of a new source of revenue.

The CBAM has a comparatively confrontational character as far as mitigation instruments are concerned, which increases the need for accompanying diplomatic efforts. The decisive factor here is not only the actual material impact that the CBAM would have on other countries. Failing to adequately address the concerns of partner countries, particularly in the Global South, threatens to exacerbate the existing crisis of confidence in international climate policy (Feist & Geden, 2023). Since its adoption in the Parliament, the international debate on the CBAM has eased up somewhat, but has by no means died down. India, for example, has turned to the WTO (WTO, 2023). Diplomatic exchange has continued in various formats, for example in a new dialog format between the EU and China (European Commission, 2023).

3. The organisation of CBAM diplomacy

“[T]he question of how can you defend CBAM and its compatibility with international trade rules, and then a systematic focus on what this may imply for third countries and how to sell CBAM to the rest of the world.” (interview 2)

The European Union has long seen itself as a pioneer in international climate policy, leading by example in reducing emissions. The climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009 (COP 15) marked a turning point in that regard when a stronger focus was put on mediation between countries in the international negotiations (Bäckstrand & Elgström, 2013; Fischer & Geden, 2015; Kulovesi, 2012; Schunz, 2015, 2019). Key loci of EU climate diplomacy are the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), to which the EU is a party in addition to its individual member states, as well as plurilateral platforms such as the Group of Seven (G7) or the Group of Twenty (G20); furthermore, climate diplomacy is also part of the EU’s bilateral and interregional relations (Delreux & Earsom, 2023; Oberthür & Dupont, 2021). Internally, the Commission, specifically the Directorate-General for Climate Action (DG CLIMA), is generally responsible for the bloc’s climate diplomacy. The Working Party on International Environment Issues – Climate Change (WPIEI-CC), which is based at the Council and prepares the international climate negotiations for the EU, is also important in this regard. As has been the case with Germany (Flachsland et al., 2023; Kahlen et al., 2022), the European Union’s lack of a coherent grand strategy for international climate cooperation has been criticised (Oberthür & Dupont, 2021).

This study conducts a descriptive analysis to unpack the internal organisation of EU’s CBAM diplomacy. It focuses on the relevant institutions within the EU: the Commission, the External Action Service, the Parliament, the Council, and the member states. Organised industry interests were certainly also important in negotiating the CBAM. However, the focus is not on these negotiations, but on the organisation of the EU’s diplomatic activities. The study period begins with the Commission’s 2019 announcement of the intention to introduce the CBAM; it ends with the agreement on the CBAM proposal between Council and Parliament in December 2022. The analysis is based on expert interviews. Semi-structured interviews were conducted from February to June 2023 with a total of 18 experts. These included members of staff of the key EU institutions (Commission, External Action Service, Parliament, Delegation to the United Nations and Permanent Mission World Trade Organization), civil servants from selected member states (Germany and France), as well as researchers at universities, research institutes, and think tanks. An overview of the interviews can be found in the annex. The interview questions were developed drawing on two additional exploratory interviews conducted in October 2022. The interviews were coded in an inductive process using the MAXQDA analysis software. They were supplemented by document research on CBAM-related diplomatic activities by EU institutions.

3.1 European Commission

“It’s not a negotiation in the end. The EU will decide on a policy, and others will have to live with it, and then they can bring a case against us, and then we’ll see what happens.” (interview 7)

As the focal point for both internal EU climate policy, climate diplomacy, and external economic relations, the Commission takes a leading role in the internal organisation of CBAM diplomacy. In fact, the Commission can be seen as a policy entrepreneur with regard to the CBAM, in that it has driven the initiative forward and shaped its substance (interviews 2, 18). At a basic level, a distinction can be made between the political leadership and the work in various Directorates-General. What both levels had in common was that their approach is described as more principled than diplomatic – in the sense that the CBAM was communicated as a done deal and partner countries therefore had to adapt to it regardless of their concerns and objections (interviews 7, 8, 14, 18).

At the political leadership level under Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, who has been in office since 2019, Frans Timmermans, then Vice-President and Commissioner for Climate Action, played a very prominent role (interviews 3, 8, 18). Both discussed the CBAM in bilateral talks with important partner countries (including China, South Korea, Japan and Thailand; interviews 7, 10, 13). The Commission’s efforts also took place during the annual UNFCCC climate summits, where the CBAM was promoted in parallel to the major multilateral negotiation tracks (interview 18), for example at a side event of the European Parliament in 2021 at COP 26 in Glasgow.

At the operational level, the lead responsibility for the CBAM was already defined in 2020, i.e. shortly after the Green Deal was presented. It rests with the Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union (DG TAXUD). It was there – and not in the Directorate-General for Climate Action – that the CBAM was originally conceived as a carbon border tax; the explicit reference to the EU ETS was added only later (interviews 1, 3). Initially, a team of just five people at DG TAXUD in the unit Indirect taxes other than VAT2Today, the unit is called CBAM, Energy and Green Taxation. (TAXUD.C.2), developed the basis for the CBAM (interviews 3, 10). In terms of communicating with partner countries, the focus, already in this early phase, was on conveying technical elements at working level (interviews 10, 14). Representatives of the Directorate-General took part in bilateral discussions with the relevant ministries of the trading partners, but also in institutions and forums such as the UNFCCC negotiations (which usually fall within the remit of DG CLIMA) or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), where the Director-General of DG TAXUD, Gerassimos Thomas, answered questions from ministers and heads of government on the operating principles of the CBAM (interviews 10, 18). The aim was to counteract the perception of the CBAM as a trade policy instrument, to emphasise its climate objectives, and to highlight opportunities for support from the EU for capacity building and the technical implementation of CBAM compatibility (interview 17). Particular focus was put on individual key partner countries. For example, the dialogue with India on technical aspects of the CBAM was intensified for strategic reasons (interview 10).

Although ostensibly focused on technical modalities, the DG TAXUD talks were ultimately of a political nature. The introduction of the CBAM was not put up for debate but, at least implicitly, presented as a given. The EU’s trading partners would have to accept and come to terms with it – regardless of any objections they might have. This approach was also influenced by the experience with public consultations on a possible carbon border adjustment held from July to October 2020, hosted by the Commission, in which representatives from partners countries were invited to participate. Only a few stakeholders from abroad took part initially in this process for the further development of emissions pricing as part of the Green Deal at the beginning of 2020, which ultimately led to the CBAM (interview 9). In retrospect, it was seen as debatable whether it was wise to kick off diplomatic efforts by conducting the discussions on the CBAM so openly (ibid.). Instead of discussing the CBAM in depth, the focus was now instead supposed to be on helping partner countries understand the design of the CBAM and make their exports to the EU compatible (interviews 14, 18).

Within the EU, DG TAXUD also played a role in relation to the member states. During the negotiations of the Commission’s CBAM proposal, DG TAXUD, in cooperation with the External Action Service, circulated a non-binding handout among the member states with answers to frequently asked questions from trading partners (interviews 1, 2, 5, 10, 15; see also section 3.2 below). The aforementioned informal expert group on the impact of the CBAM was also created in this context, in which third countries could play an observer role (European Commission, 2022).

Even though DG TAXUD was primarily responsible for the development of the CBAM, the Directorate-General for Climate Action (DG CLIMA) also played an important role. Alongside WPIEI-CC, it is generally responsible for the EU’s climate diplomacy. DG CLIMA, which is in charge of the EU ETS, was involved in CBAM diplomacy as part of an interservice group3The interservice group consisted of 17 Directorates-General as well as the EEAS and the Legal Service and met until March 2021 (Directorates-General CLIMA, TRADE, ENER, BUDGET, NEAR, JRC, COMP, GROW, ECFIN, INTPA, MOVE, ENV, AGRI, JUST, RTD, REA, MARE). (interview 10), within which the Directorates-General for Trade (DG TRADE), International Partnerships (DG INTPA) and Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR) were also particularly relevant. During the development of the Commission’s proposal, they ensured that external trade relations were duly considered, for example with regard to the WTO compatibility of the CBAM (interview 15). The Directorate-General for Trade (DG TRADE) was also responsible for leading the discussions within the World Trade Organization (interviews 7, 10). DG TRADE worked closely with DG TAXUD in this context. After the meetings of the interservice group had concluded and the proposal had been negotiated between the Council and the Parliament, these Directorates-General continued to play a role in CBAM diplomacy. DG CLIMA and DG TRADE in particular, as well as DG TAXUD, used their own communication channels with the member states (interview 15).

3.2 European External Action Service

“[T]he proposal is out – big splash. The whole world is interested to hear about this. We ensure that our delegations are well-equipped to reply to questions as much as possible.” (interview 15)

The European External Action Service (EEAS) is made up of EU staff on the one hand and staff from the national foreign services of the member states on the other. Within EU climate diplomacy, the EEAS has gained in capacity since the Paris Agreement (Earsom & Delreux, 2023). One of the EEAS’s tasks is to weigh up the external impact of internal EU policy measures and to develop appropriate strategies for monitoring these measures externally (interview 15). In this context, the Green Transition department (GLOBAL.GI.3), which is part of the Global Issues division (GLOBAL.GI.DMD), has been involved in the discussions on the CBAM design from the outset in order to keep an eye on the external effects (interview 15). In the context of CBAM diplomacy, the EEAS provided substantive material but, unlike the Commission, did not adopt the CBAM as its own political project (interviews 2, 3, 18). Instead, the aim of the External Action Service’s efforts was in particular to establish a certain degree of uniformity in the arguments put forward in favour of the CBAM in the diplomacy of the EU member states.

In this respect, the EEAS was primarily active as a coordinator at the interface between the Commission, in particular DG TAXUD, and the EU delegations in international organisations and third countries. Key positions, wordings, and technical explanations were agreed to counter opposition from third countries and to explain the intentions and expected effects of the CBAM (interviews 2, 5, 15). Like the Commission’s Directorates-General, the EEAS has its own channels for passing on information to the foreign ministries of the member states. These include, in particular, the Green Diplomacy Network, which has established itself as a core element for coordinating European climate diplomacy, and the Energy Diplomacy Group (Torney & Cross, 2018; interviews 2, 15). The EU’s bilateral delegations also made it possible to collect reactions and questions from individual countries. In cooperation with DG TAXUD, the EEAD prepared answers to frequently asked questions based on this information for the EU member states in order to facilitate a coherent approach in their external diplomacy. The member states received talking points containing previously agreed wordings. However, it is of course up to the member states whether they use these wordings in their engagements with third countries (interview 2). The EEAS was generally much less visible than DG TAXUD for the member states when communicating with the EU (interviews 1, 5). During the internal negotiations on the CBAM draft between the Council and the Parliament, the EEAS also had little visibility vis-à-vis these institutions (interview 18).

The EEAS was also active through the more than 140 EU delegations to international organisations worldwide, in particular the Permanent Mission to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Delegation to the United Nations (interview 16). The Mission to the WTO is formally part of the External Action Service, but in practice, many delegates hail from DG TRADE and therefore maintain close personal links to the Commission (interview 7). As part of CBAM diplomacy, the Mission actively endeavoured to put the border adjustment mechanism on the agenda at the WTO in order to generate more attention (interview 7). In contrast to the more technical focus of the Commission’s Directorates-General, however, the Mission rather engaged in “blanket diplomacy”, aiming to create general understanding instead of discussing concrete mechanisms and implementation methods with individual partner countries (ibid.). However, the EEAS also specifically engaged in talks with countries that did not accept the EU’s position and threatened to take action under trade law (interview 2). The more specific the concerns of third countries related to technical details in this context, the easier it was for the EEAS to respond (interview 7). Overall, the focus of diplomatic efforts following the adoption of the CBAM is now in the implementation phase shifting towards a more targeted approach aimed at individual partner countries (interview 15).

3.3 European Parliament

“Für uns viel, viel, viel mehr problematisch als dritte Länder waren unsere Länder, also unsere Mitgliedsstaaten. Und es war unser Ziel, dass unsere Mitgliedsstaaten zufrieden sind, und natürlich, dass alles legal bleibt.“ (interview 11)

[Our countries, i.e. our member states, were of a much, much, much higher concern for us than third countries. And it was our goal that our member states be satisfied and, of course, that everything remain compliant.]

The European Parliament has taken on a growing role in international climate policy over the past 15 years. Since the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force, it has had the ability veto international treaties negotiated by the Commission (Biedenkopf, 2015). In addition, individual members of parliament take part in UN climate negotiations or hold bilateral informal talks (Delreux & Burns, 2019). As the MEPs come from different countries, arriving at a common position even within one parliamentary group can be time-consuming (interview 11). The ENVI committee and rapporteur Yannick Jadot published an initiative report Towards a WTO-compatible EU carbon border adjustment mechanism (Jadot et al., 2021), which the Parliament adopted in March 2021. In its position on the European Green Deal of 15 January 2020, the EU Parliament had previously supported the Commission’s intention to develop a WTO-compatible carbon border adjustment system (European Parliament, 2020).

While the Parliament considered the CBAM several times, it was still the Commission that was responsible for drafting it (interview 4). Accordingly, the Parliament’s efforts to consult with partner countries on the CBAM were sporadic. The Parliament’s work focused more on the implications of the CBAM for the member states and the industries based there than on foreign affairs (interviews 11, 18). The trilogue with the Commission and the Council focused on the sectors that the CBAM should cover (interview 10). Some individual MEPs, however, stood out. They were closely involved in the process due to their instrumental role in the internal EU development and agreement on the CBAM (interviews 4, 18). In particular, the rapporteur responsible for the CBAM proposal since September 2021, Mohammed Chahim (S&D, Netherlands), and the Chair of the Committee on the Environment, Pascal Canfin (Renew Europe, France), played an important role (interviews 3, 9, 11, 13, 14, 18). Both Chahim and Canfin, who led a delegation from the European Parliament at COP 26, exchanged views with third countries. For example, Chahim travelled to Washington in March 2022 and spoke with members of Congress (Chahim, 2022; interviews 5, 8 and 13). In comparison to the Commission, the Parliament’s diplomatic communication was more public in nature (interview 14). The six shadow rapporteurs of the CBAM proposal also maintained relationships with embassies and representations of trading partners, including Canada and South Korea (interview 11). Furthermore, they were frequently contacted by interest groups representing European industry, such as the steel industry, which have some of their production located in third countries (interview 4).

3.4 European Council and member states

“[F]rom the council perspective, […] it’s a bit like each country does its own diplomacy. […] I mean, I’m not a diplomat, but I don’t think the diplomacy at the EU level is extremely well coordinated.” (interview 5)

The diverging priorities of Germany and France with regard to the CBAM’s introduction shaped the process at the Council and member-state level. Differences between the member states were discussed and resolved until the Council was able to develop a common position on the CBAM that could then be negotiated with the Parliament (interview 2). France had long been a supporter of a CBAM and took over the agenda-setting, particularly during its Council Presidency in the first half of 2022. Under the French Presidency, the Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) reached agreement on a general approach. Germany, on the other hand, was initially sceptical about the idea and preferred a Nordhaus-style climate club, at least as a supplementary format for international climate cooperation (interviews 1, 5). During the trilogue negotiations, Germany held bilateral talks with the Commission on the CBAM’s design in order to clarify open questions. The positions of the other member states ranged from support and approval to rejection of the general approach, for example by Poland. National economic interests were vocal in the individual member states during this phase. Specifically, European industry was concerned about possible trade sanctions (interview 14). France’s initiative ultimately prevailed despite initial reservations in the Commission (interview 3), until the Commission essentially co-opted the CBAM project when president Ursula von der Leyen took office.

The EU member states had little ownership of the CBAM for most of the time (interview 14). Until the tenure of the French presidency in the first half of 2022, there was therefore, expectedly, little CBAM-related activity in the Council. Individual member states held bilateral discussions on the CBAM, albeit often in conjunction with other topics, such as the G7 climate club or the Inflation Reduction Actin the US (interview 1). Despite the guidance provided by the External Action Service, member states did take very different positions (ibid.). France also used its own diplomatic channels to promote the CBAM outside the EU (interview 14).

Discussions about a potential climate club coincided with the international talks on the CBAM. Establishing a climate club was an explicit goal enshrined in the coalition agreement of Germany’s new government in 2021 (SPD et al., 2021). Chancellor Olaf Scholz had already spoken out in favour of a climate club in 2020, then as Federal Minister of Finance, and strongly pushed the idea as part of the German G7 presidency in 2022 – despite concerns within the German government and weak prospects within the G7 (Dröge & Feist, 2022; Feist, 2023).4While the G7 climate club was formally launched at COP 28, it has now taken a very different form than originally envisioned (Feist, 2023). Any possible relationship between the climate club and the CBAM was initially unclear. In September 2022, Commissioner Timmermans expressed the possibility that the EU and the US could establish a climate club under certain conditions and thus the US could remain excluded from the CBAM (Simon, 2022). Ultimately, the diplomatic strands on the CBAM and the G7 climate club neither significantly complemented nor constrained each other, nor even overlapped. Germany did not block the drafting of the CBAM but withdrew from active participation in the discussions on the text (interview 5). Similarly, France was not fundamentally opposed to the G7 climate club but had concerns that all members would automatically be excluded from the CBAM (ibid.).

4. Summary and discussion

The political efforts surrounding the CBAM during the examined period focused on negotiating the details within the EU, i.e. between the member states and the EU institutions, primarily the Commission. The bulk of political resources were spent on this (interviews 3, 14, 18). The draft text for the CBAM was not significantly amended to take the concerns of partner countries into account (interview 2). External discussions with the EU’s trading partners, who would have to adapt to the CBAM, had a relatively low priority. In particular, the Commission had no discernible interest to incorporate the concerns of third countries into the process and instead presented the CBAM as a given fact that trading partners would have to come to terms with.

CBAM diplomacy was formally and de facto undertaken predominantly by the Commission. Individual Directorates-General had a specific focus and introduced partner countries to the technical elements of the CBAM (interview 17). Across the EU as a whole, however, the process was fragmented and only coordinated to a limited extent. To the extent that there was a division of labour, it concerned technical communication, primarily through DG TAXUD, versus political communication with partner countries, through the Commission’s leadership and a few individual members of parliament. There was no coordination or division of labour according to countries or groups of countries (interview 18). The EU’s CBAM diplomacy was more of a reactive response to emerging resistance than a strategic approach from the outset (interview 14). A comprehensive outreach strategy was only developed for the period after the formal launch of the CBAM in October 2023 (interview 10). The External Action Service endeavoured to create the basis for coherent communication, supporting the internal CBAM project diplomatically. However, it, too, primarily addressed technical questions that partner countries had. Individual members of parliament stood out in their diplomatic efforts, but overall, the Parliament’s perspective was also mostly inward-looking.

This reflects well-known deficits in coordinating internal responsibilities in the CBAM as well as in other areas of EU climate diplomacy. “EU external action in international fora remains the purview of a series of different venues that do not necessarily share the same priorities, constituents or working methods, nor do they regularly coordinate with each other.” (Delreux & Earsom, 2023). The relative isolation of the EU institutions from each other hinders more comprehensive climate diplomacy (ibid.). Moreover, these institutions do not have unlimited climate diplomacy capacities, which exacerbates the effects of a lack of coordination (Delreux & Earsom, 2023; Feist, 2023). The internal organisation of CBAM diplomacy did not satisfy the hopes for a more proactive Grand Climate Strategy for the European Union (Oberthür & Dupont, 2021). The prioritisation of the CBAM in external communication was by no means uniform among member states and among the EU institutions involved (Interview 14).

However, effective European climate diplomacy requires coherence between EU member states and EU institutions (Oberthür & Dupont, 2021; Schunz, 2019). More thorough coordination of CBAM diplomacy would have allowed for more sensitivity to the international context (see Schunz, 2015). If, from the EU’s perspective, the central question was “how to sell CBAM to the rest of the world” (interview 2), the question that follows is: To whom? Which form of diplomacy is most suitable depends on what third countries understand the intended impact mechanism of the CBAM to be (Kulovesi, 2012; Pander Maat, 2022) – is it seen as an enabling measure for the EU’s internal climate action, a protectionist measure, a unilateral instrument with international effects? The EU’s response to the reactions ought to be tailored to the respective country (Interview 8). Which partner countries should be addressed and what interests do they have? (Dokk Smith et al., 2023; Petri, 2020)? Answering this question adequately requires consultations with trading partners, knowledge transfer and capacity building, as well as ongoing dialogues in the relevant international organisations (UNFCCC, WTO, etc.), taking into account the changing geopolitical context (Dröge & Panezi, 2022).

Coordination of CBAM diplomacy was complicated by the timing of the EU’s internal negotiations and international reactions to the draft (interviews 1, 13, 17). As there was no internal agreement on the CBAM, there could not be a coherent external approach: “[The CBAM] adds uncertainty around trade partners. It’s one of those rogue things where no one really understands what it is because it is nothing yet, it’s a negotiation.” (interview 14) “You cannot immediately have an external position directly.” (interview 17) CBAM diplomacy proved to be quite typical of the EU’s efforts in international climate cooperation, insofar as the complex internal political and institutional circumstances are in constant interaction with the limitations and opportunities of external efforts (Oberthür & Pallemaerts, 2010). However, if the rather uncoordinated and one-sided engagement with third countries has contributed to the CBAM being perceived as unmalleable, this may, in this case, have served to internally legitimise more ambitious climate policies in partner countries (interview 10). The rigidity of internal EU coordination in the face of international concerns, therefore, can turn out to be an advantage. Insofar as the CBAM is primarily an expression of the EU’s claim to leadership in ambitious climate policy (Pirlot, 2022) the circumstances have protected the CBAM from weakening in the face of international pressure.

In this light, further research could examine which aspects of CBAM diplomacy ultimately had the decisive effect in the given context. One can hypothesise, for instance, that the initial international outcry was exaggerated and did not accurately reflect the actual trade and climate policy explosiveness of the CBAM. As it seems at the moment, however, unless the bulk of the trade-related complaints and retaliations are yet to come, the EU’s CBAM diplomacy has – intentionally or coincidentally – turned out to be an effective response in terms of its character and scope, because the technical focus of the talks did not provide opponents with a tangible target for their political concerns.

Appendix: List of interviews

This Ariadne analysis was prepared by the above-mentioned authors of the Ariadne consortium. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the entire Ariadne consortium or the funding agency. The content of the Ariadne publications is produced in the project independently of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Literaturangaben

African Climate Foundation & Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa. (2023). Implications for African Countries of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in the EU. African Climate Foundation;Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa. https://africanclimatefoundation.org/news_and_analysis/implications-for-african-countries-of-a-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-in-africa/

Bäckstrand, K., & Elgström, O. (2013). The EU’s Role in Climate Change Negotiations: From Leader to ‘Leadiator’. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(10), 1369–1386. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.781781

Barrett, S., & Stavins, R. (2003). Increasing Participation and Compliance in International Climate Change Agreements. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 3(4), 349–376. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:INEA.0000005767.67689.28

Bellora, C., & Fontagné, L. (2022). EU in Search of a WTO-Compatible Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4168049

Biedenkopf, K. (2015). The European Parliament in EU external climate governance. In S. Stavridis & D. Irrera (Hrsg.), The European Parliament and its International Relations (1. Aufl., S. 92–108). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315713984-7/european-parliament-eu-external-climate-governance-1-katja-biedenkopf

Brandi, C. (2021). Priorities for a development-friendly EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) (20/2021; Briefing Paper). Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik. https://doi.org/10.23661/BP20.2021

Campolmi, A., Fadinger, H., Forlati, C., Stillger, S., & Wagner, U. (2024). Designing effective carbon border adjustment with minimal information requirements: Theory and empirics. (19; Single Market Economy Papers). European Commission. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2873/336612

Chahim, M. (2022). United States lawmakers are at a CBAM tipping point. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/opinion/united-states-lawmakers-are-at-a-cbam-tipping-point/

Christoff, P. (2010). Cold Climate in Copenhagen. China and the United States at COP15. Environmental Politics, 19(4), 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2010.489718

Cosbey, A., Mehling, M., & Marcu, A. (2021). CBAM for the EU: A Policy Proposal. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3838167

Council of the European Union (Regisseur). (2022, März 15). Economic and Financial Affairs Council: Public session. https://video.consilium.europa.eu/event/en/25536

de Jong, S. (2022, Juli 25). The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Transatlantic Policy Center, American University. https://www.american.edu/sis/centers/transatlantic-policy/07252022-the-eus-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism.cfm

Delreux, T., & Burns, C. (2019). Parliamentarizing a Politicized Policy: Understanding the Involvement of the European Parliament in UN Climate Negotiations. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2093

Delreux, T., & Earsom, J. (2023). Missed opportunities: The impact of internal compartmentalisation on EU diplomacy across the international regime complex on climate change. Journal of European Public Policy, online, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2217849

Dokk Smith, I., Øverland, I., & Szulecki, K. (2023). The EU’s CBAM and Its ‘Significant Others’: Three Perspectives on the Political Fallout from Europe’s Unilateral Climate Policy Initiative. Journal of Common Market Studies, jcms.13512. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13512

Dröge, S. (2011). Using border measures to address carbon flows. Climate Policy, 11(5), 1191–1201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2011.592671

Dröge, S. (2021). Ein CO₂-Grenzausgleich für den Green Deal der EU: Funktionen, Fakten und Fallstricke (2021/S 09; SWP-Studie). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2021S09/

Dröge, S., & Feist, M. (2022). Der G7-Gipfel: Schub für die internationale Klimakooperation? Optionen und Prioritäten für die deutsche G7-Präsidentschaft (2022/A 33; SWP-Aktuell). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2022A33/

Dröge, S., & Panezi, M. (2022). How to Design Border Carbon Adjustments. In M. Jakob (Hrsg.), Handbook on trade policy and climate change (S. 163–179). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839103247

Earsom, J., & Delreux, T. (2023). A New Kid in Town? The Evolution of the EEAS Headquarters’ Involvement in EU Climate Diplomacy. European Foreign Affairs Review, 28(3), 283–304.

Eckersley, R. (2020). Rethinking leadership: Understanding the roles of the US and China in the negotiation of the Paris Agreement. European Journal of International Relations, 26(4), 1178–1202.

Eicke, L., Weko, S., Apergi, M., & Marian, A. (2021). Pulling up the carbon ladder? Decarbonization, dependence, and third-country risks from the European carbon border adjustment mechanism. Energy Research & Social Science, 80, 102240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102240

Espa, I., Francois, J., & van Asselt, H. (2022). The EU Proposal for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM): An Analysis under WTO and Climate Change Law (WTI Working Paper 06/2022). World Trade Institute. https://doi.org/10.48350/174432

Europäische Union. (2021). Verordnung (EU) 2021/1119 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 30. Juni 2021 zur Schaffung des Rahmens für die Verwirklichung der Klimaneutralität und zur Änderung der Verordnungen (EG) Nr. 401/2009 und (EU) 2018/1999. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021R1119

Europäische Union. (2023a). Richtlinie (EU) 2023/959 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 10. Mai 2023 zur Änderung der Richtlinie 2003/87/EG über ein System für den Handel mit Treibhausgasemissionszertifikaten in der Union und des Beschlusses (EU) 2015/1814 über die Einrichtung und Anwendung einer Marktstabilitätsreserve für das System für den Handel mit Treibhausgasemissionszertifikaten in der Union (2023/959). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32023L0959

Europäische Union. (2023b). Verordnung (EU) 2023/956 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 10. Mai 2023 zur Schaffung eines CO2-Grenzausgleichssystems (Text von Bedeutung für den EWR) (PE/7/2023/REV/1). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023R0956

European Commission. (2022, Juli 28). Informal expert group on analytical methods for the monitoring, reporting, quantification and verification of embedded emissions in goods under the scope of CBAM (E03862). Register of Commission expert groups and other similar entities. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/expert-groups-register/screen/expert-groups/consult?lang=en&groupID=3862

European Commission. (2023, Juli 24). Joint Press Release following the Fourth EU-China High Level Environment and Climate Dialogue. European Commission. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/news-your-voice/news/joint-press-release-following-fourth-eu-china-high-level-environment-and-climate-dialogue-2023-07-24_en

European Commission. (2024, März 8). The European Green Deal. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/story-von-der-leyen-commission/european-green-deal_en

European Parliament. (o. J.). Fit for 55 package under the European Green Deal. European Parliament. Abgerufen 1. September 2023, von https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/package-fit-for-55

European Parliament. (2020). The European Green Deal: European Parliament resolution of 15 January 2020 on the European Green Deal (2019/2956(RSP)). European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0005_EN.pdf

European Parliament. (2023). European Parliament legislative resolution of 18 April 2023 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism (COM(2021)0564 – C9-0328/2021 – 2021/0214(COD)). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2023-0100_EN.html

Farrokhi, F., & Lashkaripour, A. (2022). Can Trade Policy Mitigate Climate Change? (STEG WP034; STEG Working Paper Series). Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://steg.cepr.org/publications/can-trade-policy-mitigate-climate-change

Feist, M. (2023). Neue Allianzen. Plurilaterale Kooperation als Modus der internationalen Klimapolitik (2023/S 09; SWP-Studie). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/plurilaterale-kooperation-als-modus-der-internationalen-klimapolitik

Feist, M., & Geden, O. (2023). Loss & Damage Finance and Mitigation Pledges: Priorities for Climate Diplomacy in 2023. Energy and Climate Diplomacy, 17, 75–84.

Fetting, C. (2020). The European Green Deal (ESDN Report). European Sustainable Development Network. https://www.esdn.eu/fileadmin/ESDN_Reports/ESDN_Report_2_2020.pdf

Fischer, S., & Geden, O. (2015). The Changing Role of International Negotiations in EU Climate Policy. The International Spectator, 50(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2015.998440

Flachsland, C., Steckel, J., Jakob, M., Fahl, U., Feist, M., Görlach, B., Kühner, A.-K., Tänzler, D., & Zeller, M. (2023). Eckpunkte zur Entwicklung einer Klimaaußenpolitikstrategie Deutschlands (Ariadne-Hintergrund). Kopernikus-Projekt Ariadne. https://doi.org/10.48485/pik.2023.007

Gangotra, A., Carlsen, W., & Kennedy, K. (2023, Dezember 13). 4 US Congress Bills Related to Carbon Border Adjustments in 2023. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/update/4-us-congress-bills-related-carbon-border-adjustments-2023

Gläser, A., & Caspar, O. (2021). Less confrontation, more cooperation: Increasing the acceptability of the EU Carbon Border Adjustment in key trading partner countries (Policy Brief). Germanwatch.

Grubb, M. (2011). International climate finance from border carbon cost levelling. Climate Policy, 11(3), 1050–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2011.582285

Healy, S., Cludius, J., & Graichen, V. (2023). Einführung eines CO2-Grenzausgleichssystems (CBAM) in der EU (Fact Sheet). Umweltbundesamt. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/einfuehrung-eines-co2-grenzausgleichssystems-cbam

Heli, S. (2021). CBAM! – Assessing potential costs of the EU carbon border adjustment mechanism for emerging economies (10/2021; BOFIT Policy Brief). Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:bof-202110252070

Hook, L. (2001, März 12). John Kerry warns EU against carbon border tax. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/3d00d3c8-202d-4765-b0ae-e2b212bbca98

Ismer, R., & Neuhoff, K. (2007). Border tax adjustment: A feasible way to support stringent emission trading. European Journal of Law and Economics, 24(2), 137–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-007-9032-8

Jadot, Y., Karlsbro, K., & Garicano, L. (2021). Towards a WTO-compatible EU carbon border adjustment mechanism (2020/2043(INI); Report). European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2021-0019_EN.html

Jakob, M. (2023). The political economy of carbon border adjustment in the EU. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 39(1), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grac044

Kahlen, L., Kachi, A., Kurdziel, M.-J., Röser, F., Höhne, N., Outlaw, I., & Emmrich, J. (2022). Climate Audit of German Foreign Policy: Assessing the alignment of German international engagement with the objectives of the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement. New Climate Institute. https://newclimate.org/resources/publications/climate-audit-of-german-foreign-policy

Kolev, G., Kube, R., Schaefer, T., & Stolle, L. (2021). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM): Motivation, Ausgestaltung und wirtschaftliche Implikationen eines CO2-Grenzausgleichs in der EU (6/21; IW-Policy Paper). Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft. https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/galina-kolev-roland-kube-thilo-schaefer-motivation-ausgestaltung-und-wirtschaftliche-implikationen-eines-co2-grenzausgleichs-in-der-eu.html

Kulovesi, K. (2012). Climate change in EU external relations: Please follow my example (or I might force you to). In The External Environmental Policy of the European Union: EU and International Law Perspectives (S. 115–148). Cambridge University Press.

Lee, C.-K. (2021). EU CBAM: Legal Issues and Implications for Korea (No. 222; KIEP Opinions). Korea Institute for International Economic Policy. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3940746

Leonard, M., Pisani-Ferry, J., Shapiro, J., Tagliapietra, S., & Wolff, G. (2021). The geopolitics of the European Green Deal (ECFR/371). European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/publication/the-geopolitics-of-the-european-green-deal/

Leturcq, P. (2022). The European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the path to Sustainable Trade Policies: From ‘Coexistence’ to ‘Cooperation’. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 1–21. Cambridge Core. https://doi.org/10.1017/cel.2022.6

Lim, B., Hong, K., Yoon, J., Chang, J.-I., & Cheong, I. (2021). Pitfalls of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Energies, 14(21), 7303. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14217303

LMDC. (2013). Implementation of all the elements of decision 1/CP.17, (a) Matters related to paragraphs 2 to 6; Ad-Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) – Submission by the Like-Minded Developing Countries on Climate Change (LMDC). https://unfccc.int/files/documentation/submissions_from_parties/adp/application/pdf/adp_lmdc_workstream_1_20130313.pdf

Magacho, G., Espagne, E., & Godin, A. (2023). Impacts of the CBAM on EU trade partners: Consequences for developing countries. Climate Policy, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2200758

Mehling, M., & Ritz, R. (2023). From theory to practice: Determining emissions in traded goods under a border carbon adjustment. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 39(1), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grac043

Mehling, M., van Asselt, H., Das, K., Droege, S., & Verkuijl, C. (2019). Designing Border Carbon Adjustments for Enhanced Climate Action. American Journal of International Law, 113(3), 433–481. BASE. https://doi.org/10.1017/ajil.2019.22

Mehling, M., van Asselt, H., Droege, S., & Das, K. (2022). The Form and Substance of International Cooperation on Border Carbon Adjustments. AJIL Unbound, 116, 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1017/aju.2022.33

Meltzer, J. (2012). Climate Change and Trade: The EU Aviation Directive and the WTO. Journal of International Economic Law, 15(1), 111–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgr036

Nordhaus, W. (2015). Climate Clubs: Overcoming Free-riding in International Climate Policy. American Economic Review, 105(4), 1339–1370. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.15000001

Oberthür, S., & Dupont, C. (2021). The European Union’s International Climate Leadership: Towards a Grand Climate Strategy? Journal of European Public Policy, 28(7), 1095–1114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918218

Oberthür, S., & Pallemaerts, M. (2010). The EU’s Internal and External Climate Policies: An Historical Overview. In S. Oberthür & M. Pallemaerts (Hrsg.), The New Climate Policies of the European Union: Internal Legislation and Climate Diplomacy (S. 27–63). Brussels University Press.

Øverland, I., & Sabyrbekov, R. (2022). Know your opponent: Which countries might fight the European carbon border adjustment mechanism? Energy Policy, 169, 113175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113175

Pahle, M., Günther, C., Osorio, S., & Quemin, S. (2023). The Emerging Endgame: The EU ETS on the Road Towards Climate Neutrality. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4373443

Pander Maat, E. (2022). Leading by Example, Ideas or Coercion? The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism as a Case of Hybrid EU Climate Leadership. European Papers – A Journal on Law and Integration, 2022 7, 55–67. https://doi.org/10.15166/2499-8249/546

Petri, F. (2020). Revisiting EU climate and energy diplomacy: A starting point for Green Deal diplomacy? (65; Egmont European Policy Brief). Royal Institute for International Relations. https://www.egmontinstitute.be/revisiting-eu-climate-and-energy-diplomacy/

Pirlot, A. (2022). Carbon Border Adjustment Measures: A Straightforward Multi-Purpose Climate Change Instrument? Journal of Environmental Law, 34(1), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqab028

Porterfield, M. (2023). Carbon Import Fees and the WTO (Report). Climate Leadership Council.

Price, R. (2020). Lessons Learned from Carbon Pricing in Developing Countries (799; K4D Helpdesk Report). Institute of Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/15336

Rat der Europäischen Union. (2022, März 15). Rat erzielt Einvernehmen über das CO₂-Grenzausgleichssystem. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/de/press/press-releases/2022/03/15/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-cbam-council-agrees-its-negotiating-mandate/

Ren, Y., Liu, G., & Shi, L. (2023). The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will exacerbate the economic-carbon inequality in the plastic trade. Journal of Environmental Management, 332, 117302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117302

Sapir, A., & Horn, H. (2020). Political Assessment of Possible Reactions of EU Main Trading Partners to EU Border Carbon Measures (PE 603.503; Briefing Requested by the INTA Committee). European Parliament’s Committee on International Trade. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EXPO_BRI(2020)603503

Sator, O., Cosbey, A., & Shawkat, A. (2022). Getting the Transition to CBAM Right: Finding pragmatic solutions to key implementation questions (250/01-I-2022/EN; Impulse). Agora Energiewende. https://www.agora-energiewende.de/en/publications/getting-the-transition-to-cbam-right/

Schunz, S. (2015). The European Union’s Climate Change Diplomacy. In J. A. Koops & G. Macaj (Hrsg.), The European Union as a Diplomatic Actor (S. 178–201). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137356857_11

Schunz, S. (2019). The European Union’s Environmental Foreign Policy: From Planning to a Strategy? International Politics, 56(3), 339–358. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0130-0

Sharma, V., & Gupta, K. (2022). Implications of Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: A case of India’s exports to European Union. Journal of Resources, Energy and Development, 18(1–2), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.3233/RED-181204

Siegel, J. (2022, Februar 24). Congress is eyeing a bipartisan climate trade policy—Thanks to Trump. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/02/24/congress-is-eyeing-a-bipartisan-climate-trade-policy-thanks-to-trump-00009490

Simon, F. (2022, September 21). US could dodge European carbon border levy, EU’s Timmermans says. Euractiv. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/us-could-dodge-european-carbon-border-levy-eus-timmermans-says/

South African Government. (2021). Joint Statement issued at the conclusion of the 30th BASIC Ministerial Meeting on Climate Change hosted by India on 8th April 2021. https://www.gov.za/nr/speeches/joint-statement-issued-conclusion-30th-basic-ministerial-meeting-climate-change-hosted

SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, & FDP. (2021). Mehr Fortschritt wagen: Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit – Koalitationsvertrag zwischen SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen und FDP. https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/1990812/1f422c60505b6a88f8f3b3b5b8720bd4/2021-12-10-koav2021-data.pdf?download=1

Szulecki, K., Øverland, I., & Dokk Smith, I. (2022). The European Union’s CBAM as a de facto Climate Club: The Governance Challenges. Frontiers in Climate, 4, 942583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.942583

Torney, D., & Cross, M. K. D. (2018). Environmental and Climate Diplomacy: Building Coalitions Through Persuasion. In C. Adelle, K. Biedenkopf, & D. Torney (Hrsg.), European Union External Environmental Policy (S. 39–58). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60931-7_3

van Asselt, H., & Brewer, T. (2010). Addressing competitiveness and leakage concerns in climate policy: An analysis of border adjustment measures in the US and the EU. Energy Policy, 38(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.08.061

Wooders, P., Cosbey, A., & Stephenson, D. (2009). Border Carbon Adjustment and Free Allowances: Responding to Competitiveness and Leakage Concerns (SG/SD/RT(2009)8). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

WTO. (2023, März 15). Environment committee draws members’ broad engagement, considers proposals to enhance work. World Trade Organization. https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news23_e/envir_15mar23_e.htm

Xinhua. (2023, September 13). Proposal of the People’s Republic of China on the Reform and Development of Global Governance. https://english.news.cn/20230913/edf2514b79a34bf6812a1c372dcdfc1b/c.html

Zhong, J., & Pei, J. (2022). Beggar thy neighbor? On the competitiveness and welfare impacts of the EU’s proposed carbon border adjustment mechanism. Energy Policy, 162, 112802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112802