Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Countries around the world have set increasingly ambitious targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change. To deliver on these targets, policymakers have (i) implemented new policy instruments, (ii) increased the stringency of existing policy instruments, and (iii) created ‘climate institutions’. A substantial body of literature is devoted to the first two phenomena. Yet we know little about climate institutions, including the different types of institutions countries create and how they affect the development and stringency of climate policy (Dubash 2021; Dubash et al. 2021).

This report therefore seeks to answer three research questions. First, what are climate institutions and how can we characterise them across countries? Second, what effects do climate institutions have on climate policymaking? Third, based on these findings, what lessons can we draw about the landscape of German climate institutions and what options exist for institutional reform? To address these questions, we propose a definition of climate institutions and develop a conceptual framework for analysing and comparing their effects on climate policymaking in four countries: Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Australia. We then draw on this framework and our comparative analysis to identify potentially promising reforms for German climate governance, especially in light of the proposed changes to the German climate law (the Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz, or KSG).

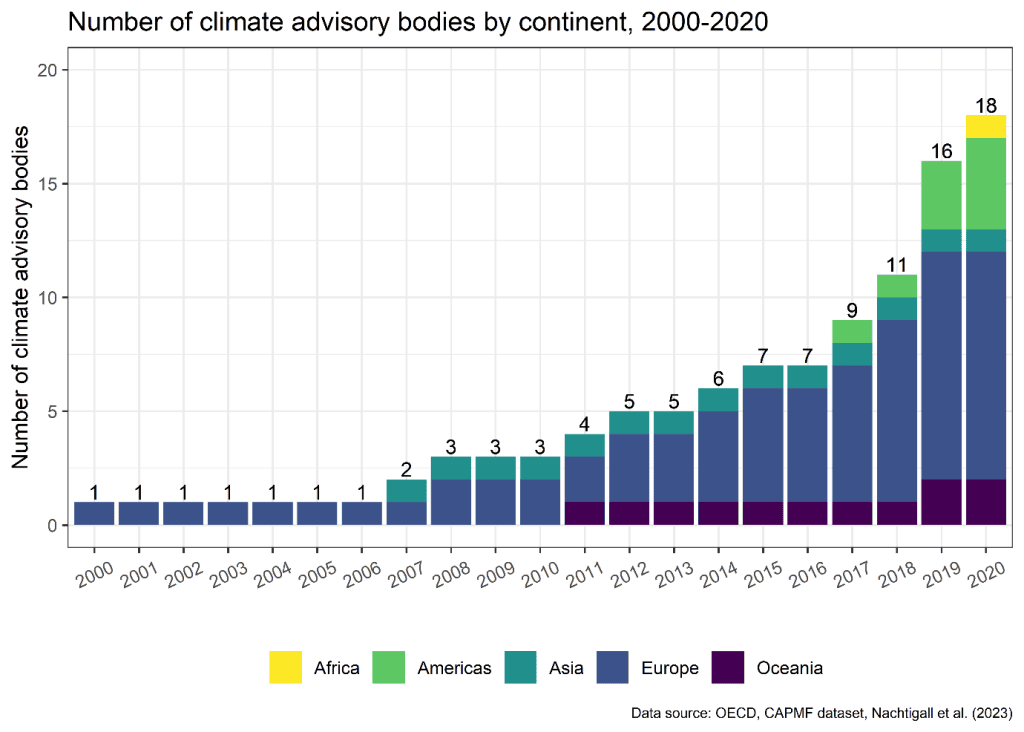

Political institutions are, generally speaking, “the formal laws, rules, and organisations that make decisions stable”, which “bind us into choices we make” and “allow us to fix our expectations of what others are likely to do” (Ansell 2023, 18). ‘Climate institutions’ are a specific type of political institution, explicitly devoted to climate change policy, which formalise the process of climate policymaking and steer its development, delivery, and potential improvement. They include, inter alia, climate framework legislation, climate advisory bodies, climate ministries, and parliamentary committees dedicated to climate policy. Over the past decade or so, these climate-specific institutions have proliferated in several countries. Figure 1, for instance, illustrates the emergence of climate advisory bodies around the world since 2000.

Though we observe the emergence of climate institutions, we lack clear definitional criteria for identifying these institutions and distinguishing them from other political institutions relevant for climate policy. This conceptual clarity is critical if we are to compare climate institutions across countries, within countries over time, and assess their effects on climate policymaking.

Existing definitions of climate institutions in the academic literature do not allow for systematic comparison of the climate institutional landscape for two reasons. First, some papers focus specifically on a single type of institution, such as climate laws (Duwe and Evans 2020), climate advisory bodies (Crowley and Head 2017; Weaver, Lötjönen, and Ollikainen 2019; Evans and Duwe 2021) or institutions focused on climate-related inter-ministerial coordination (von Lüpke, Leopold, and Tosun 2023), and therefore preclude analysis of the range of climate institutions involved in policymaking. Second, others adopt encompassing definitions that cover multiple types of institutions (MacNeil 2021; Guy, Shears, and Meckling 2023). But these obscure important differentiation among institutions, especially formal and informal institutions, and the lack of easily replicable criteria limits comparative analysis. Our definition seeks to cover multiple institutions, while its formalistic focus ensures a high degree of replicability, allowing us to distinguish between ‘climate institutions’ and the larger set of institutions relevant to climate-policymaking.

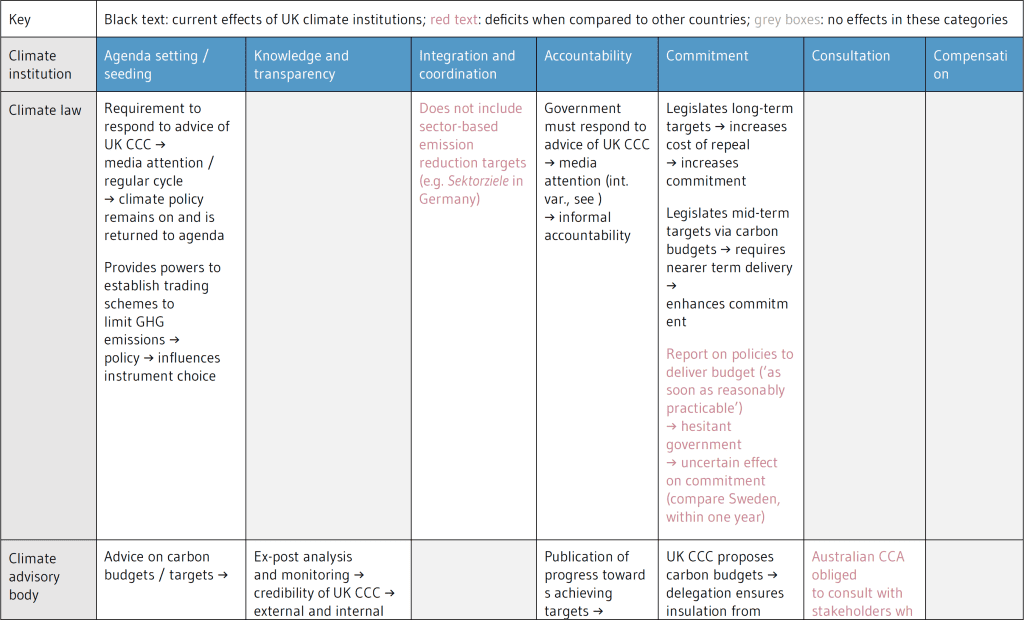

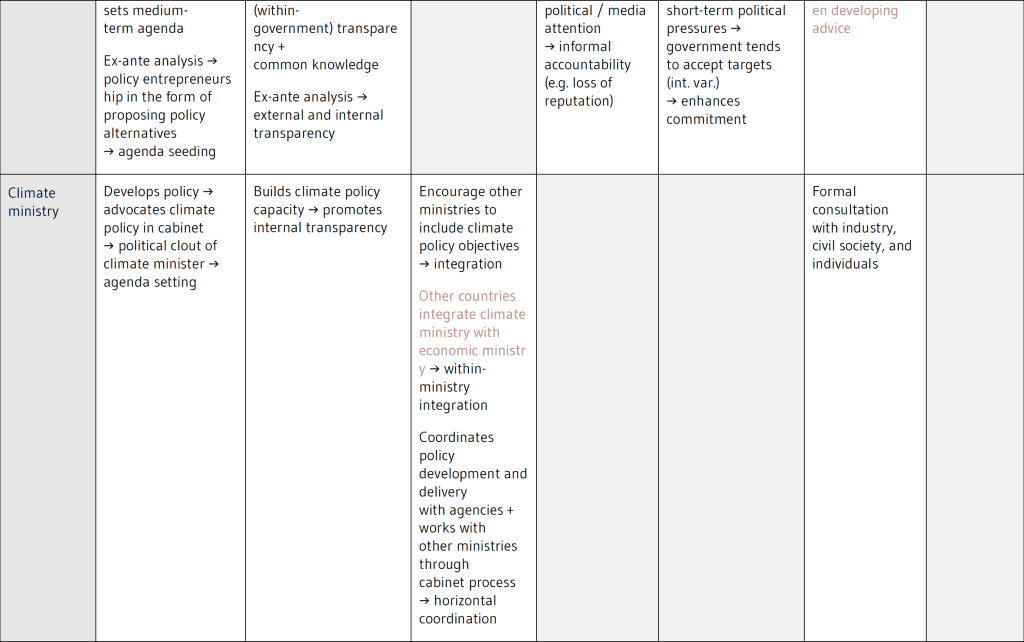

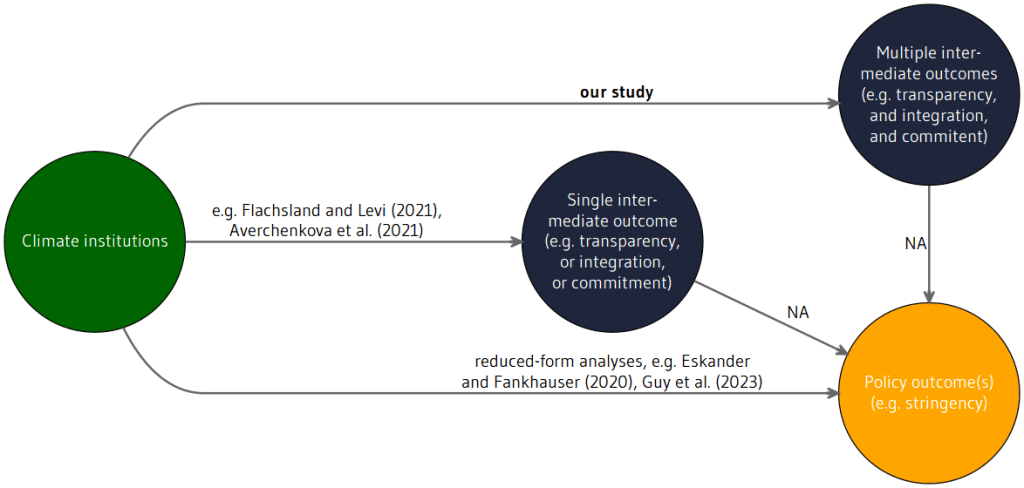

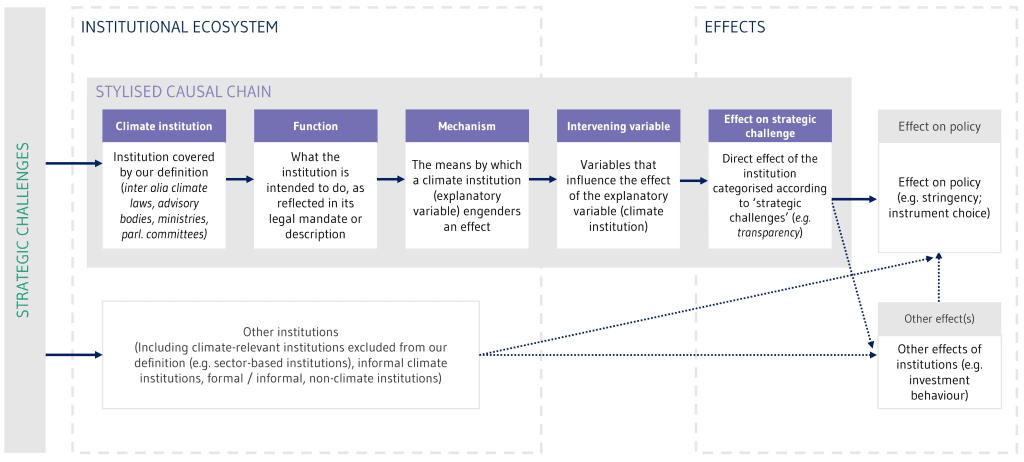

The climate institutions literature also offers no ‘off-the-shelf’ framework for comparing the effects of multiple1There exist, however, frameworks for analysing the effects of a single type of institution across countries, such as the one developed by Evans and Duwe (2021). climate institutions on policymaking. Indeed, most of the literature focuses on the emergence of climate institutions, rather than their effects (Lorenzoni and Benson 2014; Torney 2017, 2019; Karlsson 2021). A very small number of studies examine the effect of the presence of certain types of institutions on climate policy performance (Eskander and Fankhauser 2020; Guy, Shears, and Meckling 2023). These are ‘reduced-form’ analyses, indicated in the bottom-most arrow in Figure 2: studies that examine the effect of one or multiple climate institutions on policy outcomes (e.g. emissions reductions or stringency) without examining how climate institutions engender these outcomes, e.g. by enhancing transparency, integration, or commitment. Others focus on the effect of climate institutions on a single intermediate outcome, an aspect of climate policymaking hypothesised to have a knock-on effect on policy outcomes (the central dark circle Figure 2). For instance, studies examine the effect of climate institutions on increasing transparency (Averchenkova, Fankhauser, and Finnegan 2021b), policy integration (Flachsland and Levi 2021), and commitment (Lockwood 2013; Averchenkova, Fankhauser, and Finnegan 2021a). To our knowledge, no studies exist analysing how these intermediate outcomes, or aspects of climate policymaking, then affect climate policy outcomes, as shown by the edges labelled ‘NA’.

Source: Own illustration.

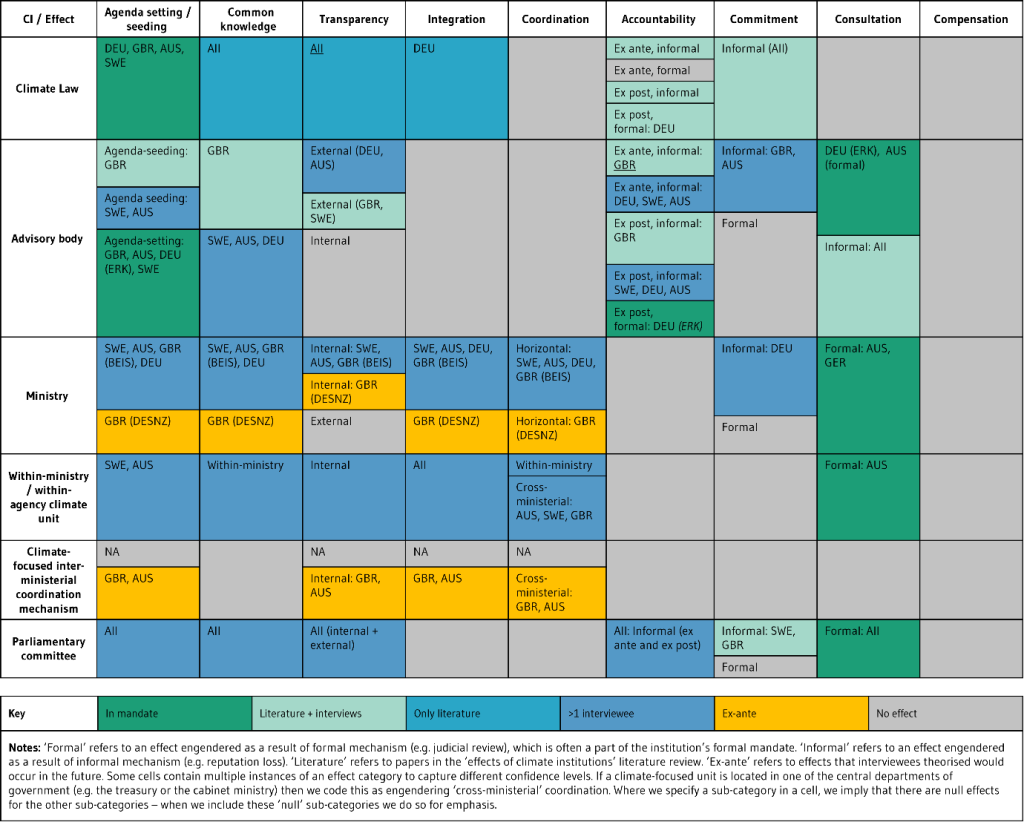

While the links between climate institutions and intermediate outcomes have received some attention in the literature, they remain under-theorised. We lack a nuanced understanding of the range of effects of climate institutions and the mechanisms by which these effects occur. Our study addresses this gap by proposing an analytical framework that (i) theorises climate institutions can have a range of potential effects, (ii) identifies mechanisms by which effects occur and intervening variables which influence them, and (iii) recognises (but does not analyse) the knock-on effects of intermediate outcomes on policy, including the stringency of targets and policy instruments.

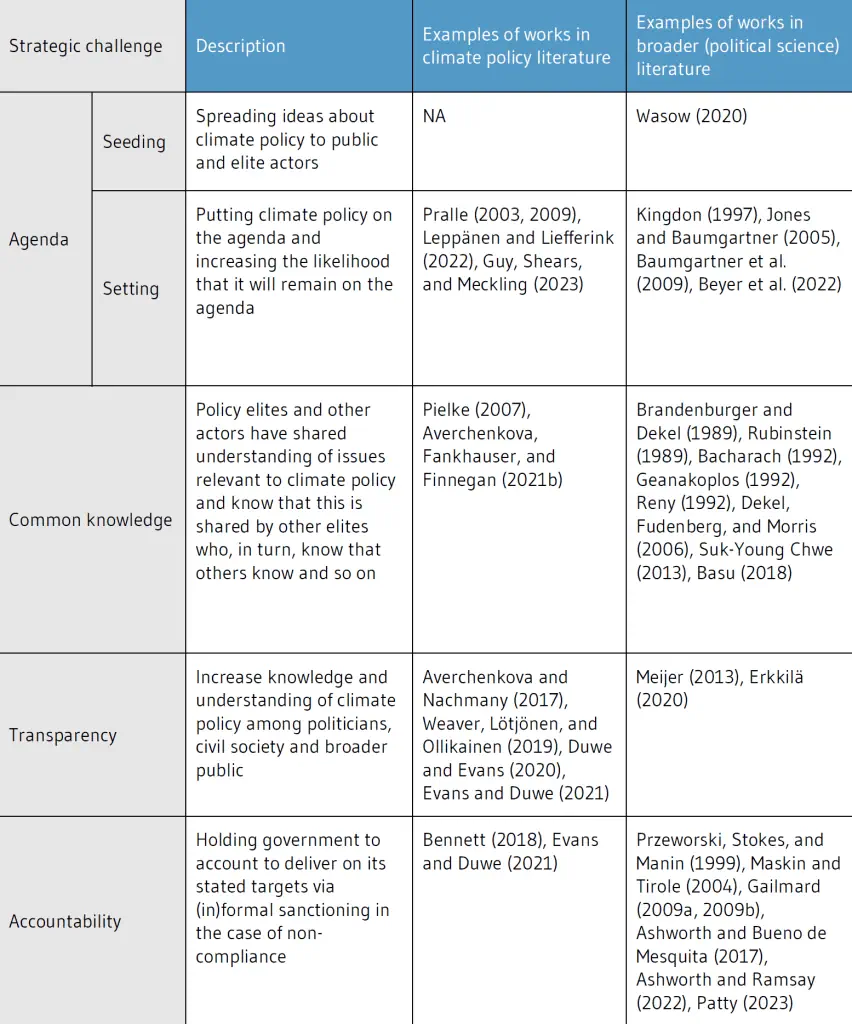

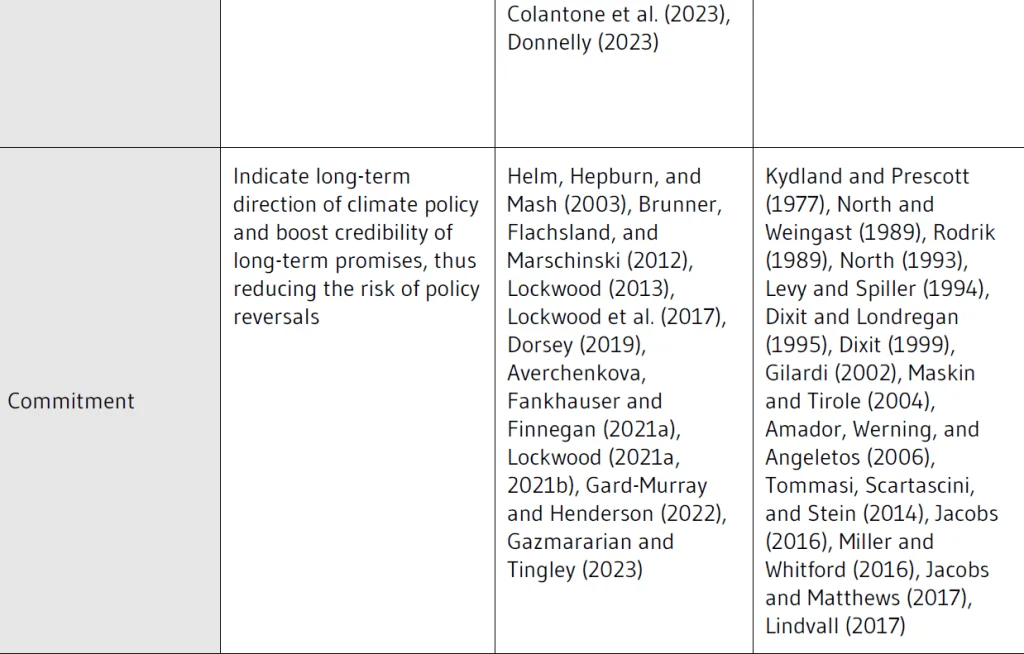

We categorise effects of climate institutions in terms of ‘strategic challenges’ in climate policymaking. Following, inter alia, Averchenkova and Nachmany (2017) and MacNeil (2021), we conceive of climate institutions as means by which policymakers respond to strategic challenges inherent in climate policymaking. These include the need for long-term commitment to emissions reduction targets, the need for common knowledge about the issue of climate change and potential solutions, the need to consult with and compensate stakeholders who stand to lose from the transition, and the need to coordinate implementation. In the absence of a theory of climate policymaking (or policymaking more broadly) that explicitly provides micro-foundations for these strategic challenges, we derive a list of these challenges from (i) a review of the role of institutions in the broader political science, comparative politics, and policy studies literatures; and (ii) a focused literature review of studies on the effects of climate institutions specifically. We apply this framework through analysis of climate institutions and their effects in four countries, drawing on desktop analysis and interviews with climate policy experts in each country (22 interviews, ~5 per country). Our cases were selected with the aim of maximising variation in macro-political context among a sample of wealthy democracies. This allowed us to better distinguish between variation arising from the functions, or design of institutions and ‘intervening variables’ that influence their effects, while holding socio-economic variables (e.g. per capita income) roughly constant.

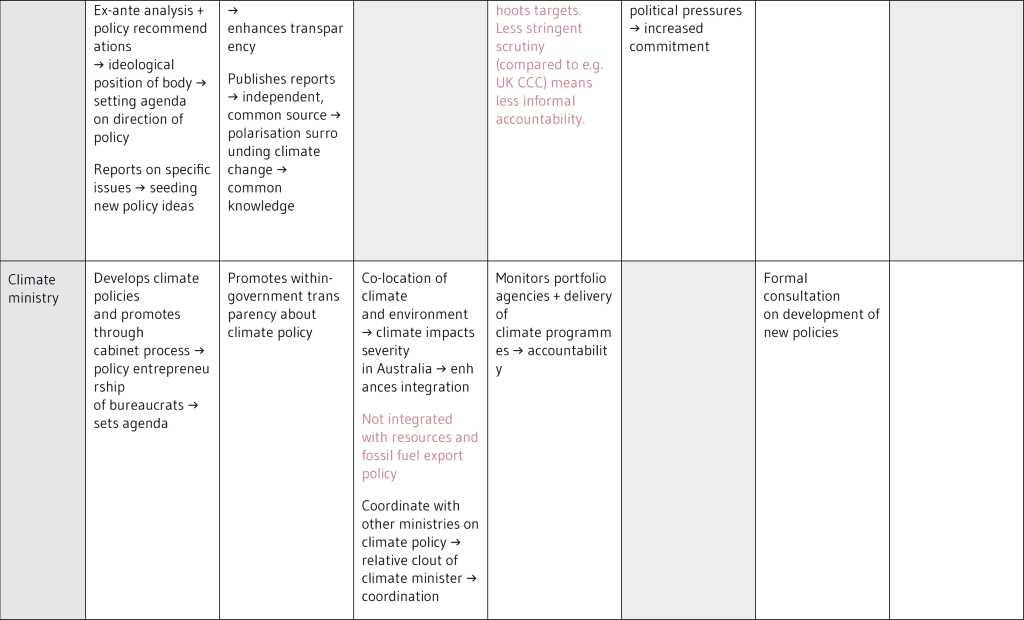

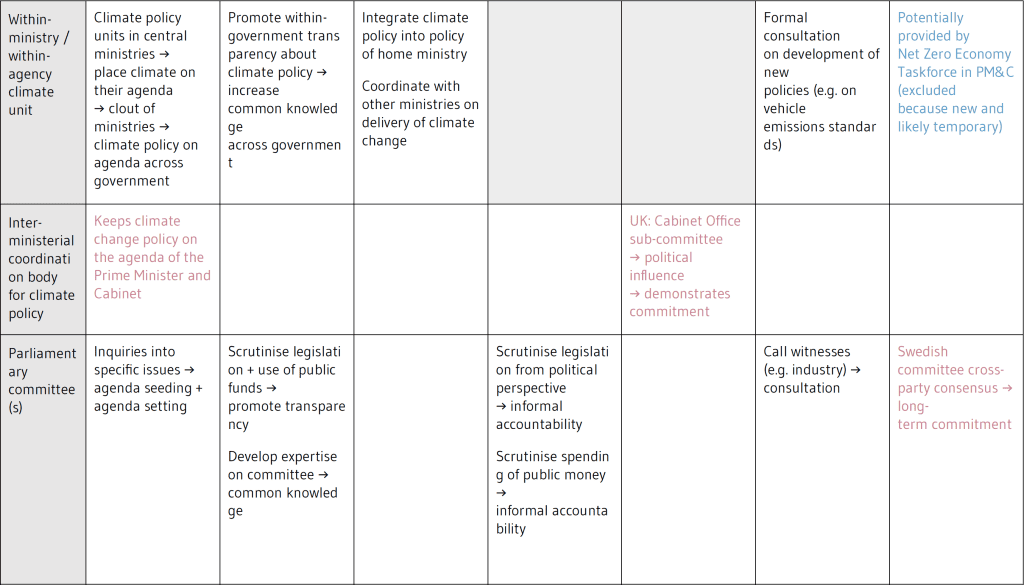

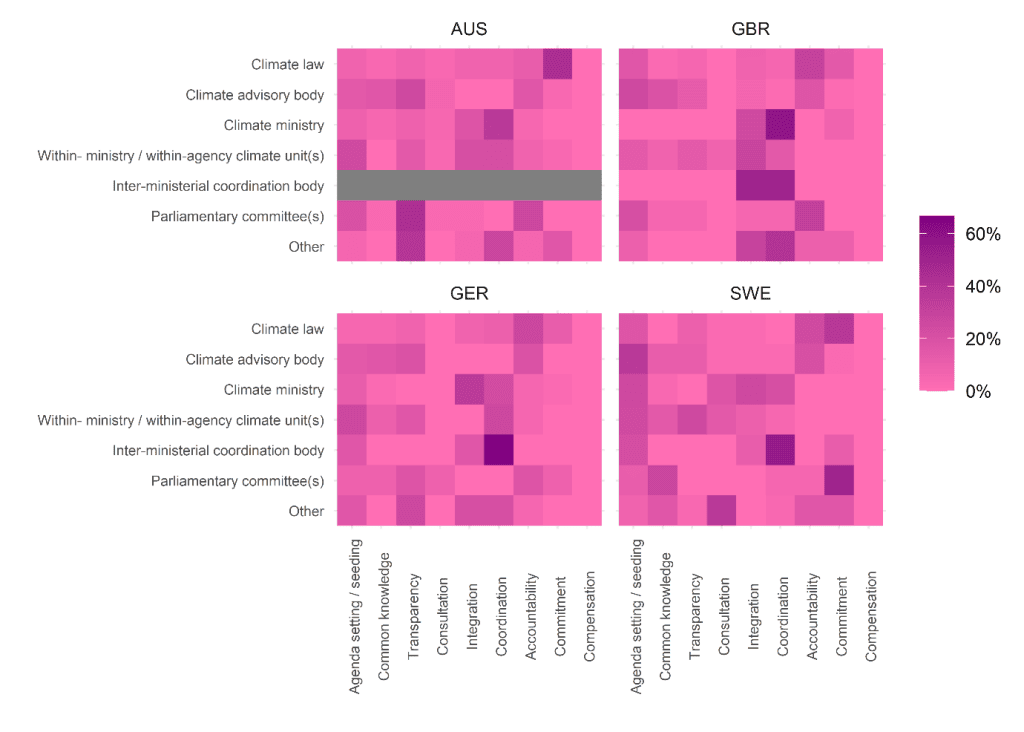

Three key findings emerge from our comparison of institutions and their effects across the four cases. First, there is a rich landscape of climate institutions in all countries in our sample. This is contrary to significant parts of the academic literature, which focuses almost exclusively on climate laws and climate advisory bodies. Second, we find that formal climate institutions tend to primarily address both the epistemic (knowledge-related) and attention-related strategic challenges present in climate policymaking. Climate advisory bodies, for instance, enhance transparency through ex-post and (in some cases) ex-ante analysis. Their credibility as knowledge brokers allows them to establish ‘common knowledge’: a shared understanding among policy elites about the problem of climate change, potential solutions, and relevant trade-offs involved in implementation.

Several types of climate institutions – including climate laws, climate advisory bodies, parliamentary committees, and climate ministries – address attention-related challenges by ensuring that climate policy is placed upon or returned to the political agenda. The regular process that climate institutions establish for climate policy development – involving scheduled analysis by advisory bodies, publication of reports, debates in parliament, replies by the government to advisory bodies’ reports, and regular policy updates – not only ensures that governments are frequently forced to consider climate policy, but also that there are regular focal points for public scrutiny of the government’s performance. Different arrangements for climate ministries – including combined ‘super-ministries’ and dedicated climate ministries – contribute to agenda setting within the government in different ways. They are supported by ‘climate units’ within other ministries, especially when those ministries possess significant political clout (e.g. finance ministries).

Third, few of the institutions covered by our definition are focused specifically on implementation of climate policy and compensating the potential ‘losers’ from climate policy. This is due, in part, to the importance of sector-specific institutions for implementation, which we do not examine in this report. The lack of compensation-related institutions may reflect the fact that many wealthy democracies have until now been able to compensate the losers from climate policy and climate change via existing institutions or via ad hoc, informal ones (e.g. Germany’s “Kohlekommission”). Where large-scale decarbonisation is particularly contentious, however, we may witness the emergence of formal, compensation-focused institutions in the future, as illustrated by Australia having recently established the Net Zero Transition Authority to deliver compensation to communities affected by the energy transition (PM&C 2023a).

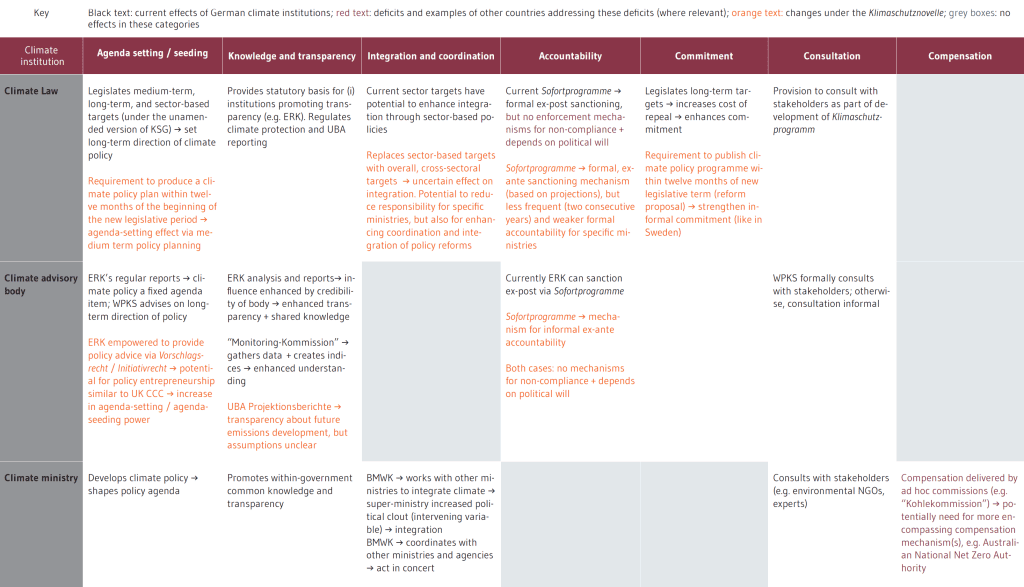

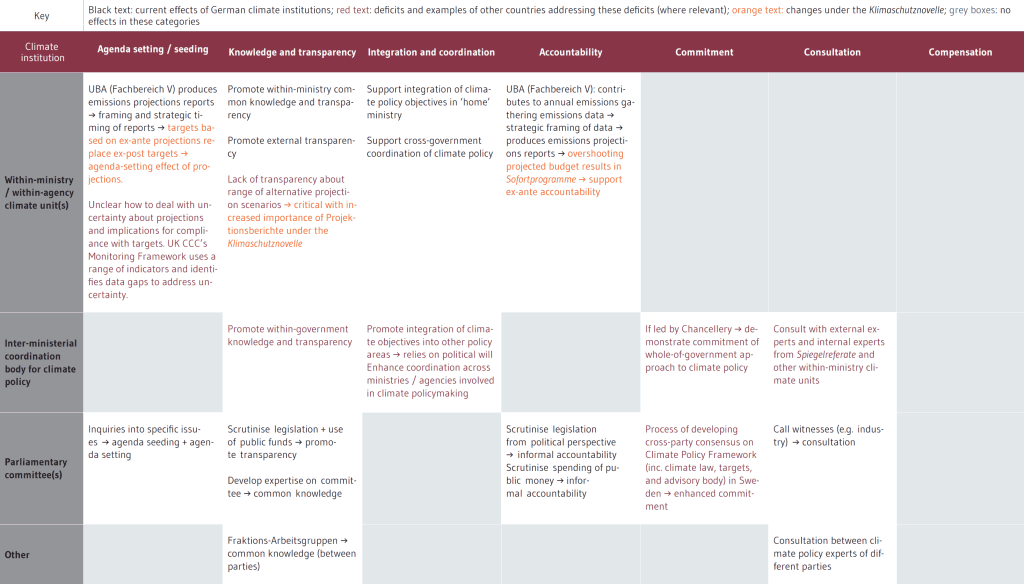

Our comparative analysis also sheds light on the potential effects of the proposed amendment (Klimaschutznovelle) to the KSG on German climate policymaking, the institutional gaps the amendment could fill, and those that will likely remain. We identify viable and potentially impactful avenues for institutional reform aimed at both increasing the Klimaschutznovelle’s effectiveness and addressing some of its key remaining deficits. These include: (i) improving integration and horizontal coordination by establishing processes for devising and evaluating cross-sectoral Sofort- and Förderprogramme as well as reinstating the currently dormant Klimakabinett (climate cabinet); (ii) enhancing transparency and accountability by increasing the scope and transparency of the modelling of the likely evolution of future emissions (Projektionsdaten) as well as the ERK’s analytical capacity; (iii) boosting the ERK’s agenda-seeding and agenda-setting powers via more active policy entrepreneurship.

This report proceeds as follows. In the following section, we detail our analytical approach, including how we approached the literature reviews and justification for our case selection. Section 3 summarises our analytical framework. Section 4 sets out our results, examining variation both within and across cases. Section 5 discusses options for improving the landscape of German climate institutions.

2. Analytical approach

This section describes our approach to developing both a definition of climate institutions and an analytical framework for ascertaining their effects on climate policymaking.

2.1 Definitions and scope

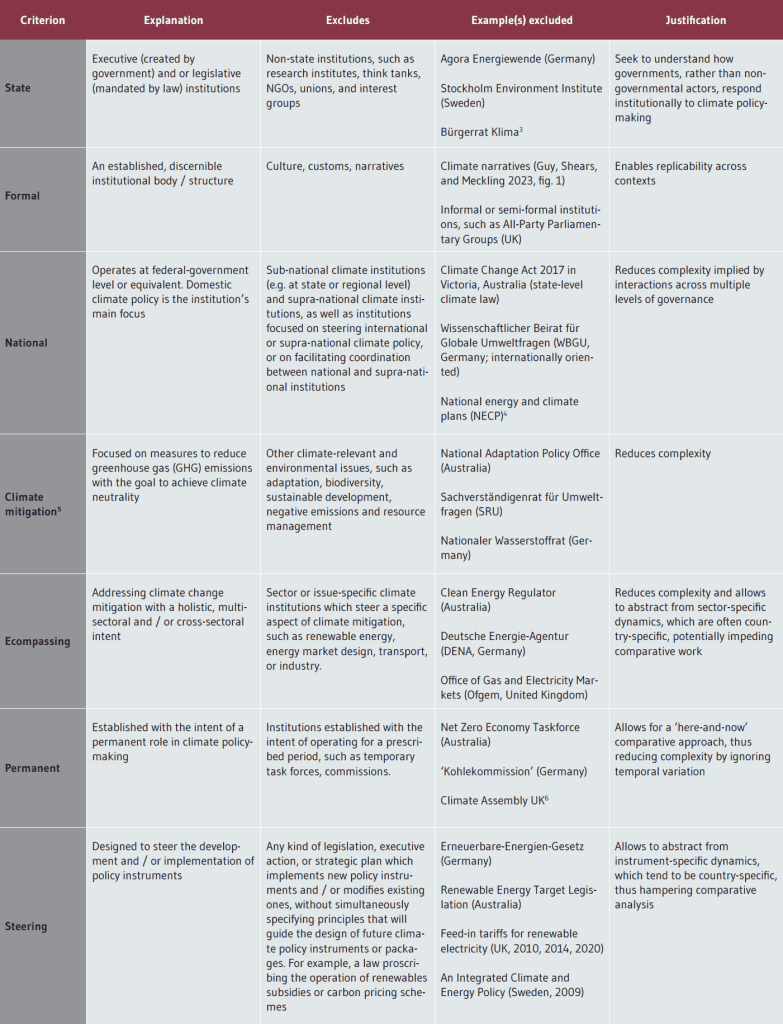

To develop a clear and easily reproducible2Following Cheibub et al. (2010) and Clark et al. (2017, 166), we define reproducibility as the property that, given identical coding rules and the same set of facts, all potential coders classify the same institutions as climate institutions. We use ‘reproducible’ and ‘replicable’ synonymously throughout the report. definition of climate institutions, we proceeded in two steps. First, we identified the conditions we deem individually necessary and collectively sufficient for an institution to be classified as a climate institution. Second, we justified why the institutions excluded by our conditions lie outside the scope of our study.

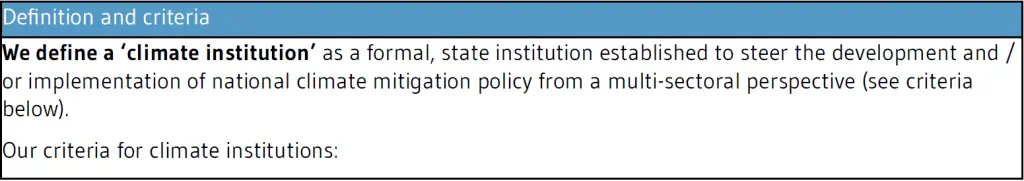

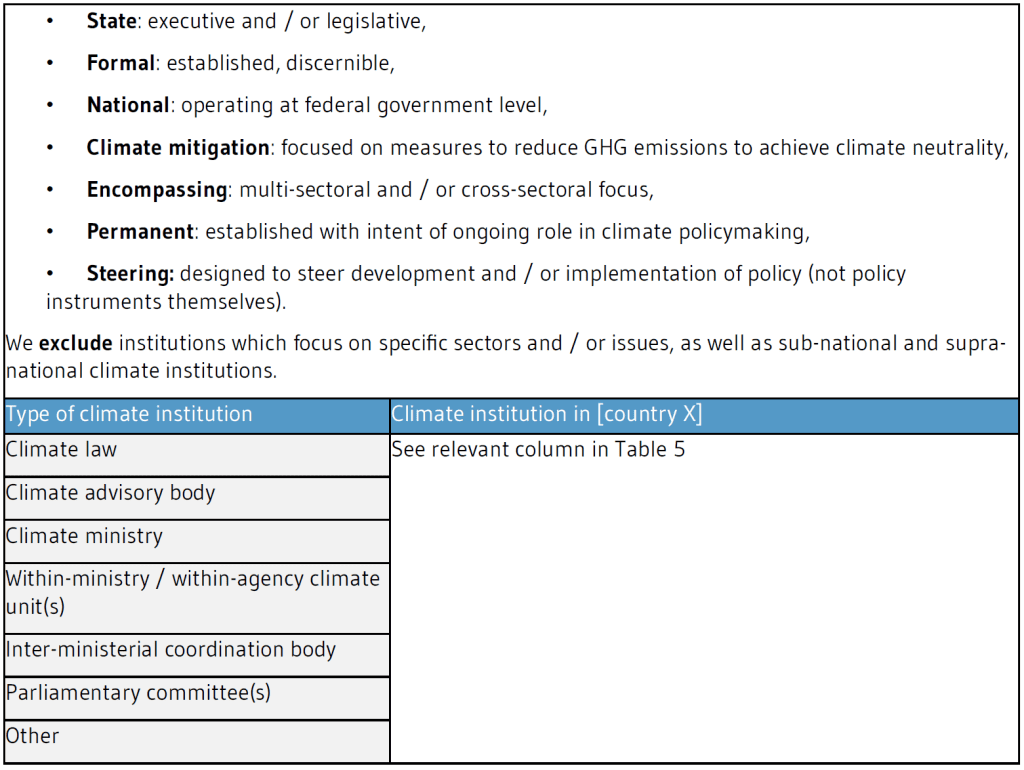

Practically, this involved first developing a list of climate institutions based on the German case (our best understood case) and then identifying the corresponding and potentially additional institutions in other countries based on detailed desktop analysis, triangulated with interviews (see 2.4.1). To harmonise this collection of institutions across the countries in our sample, we defined a climate institution as a formal, state institution established to steer the development and / or implementation of national climate mitigation policy from a multi-sectoral perspective. The specific criteria and justifications for choosing these criteria are detailed in Table 1, below (see Table 5 in section 4.2 for the full table of institutions which meet these criteria).

3The official sponsor was BürgerBegehren Klimaschutz e.V. (Bürgerrat Klima n.d.), i.e. a non-profit organisation., 4By 31 December 2018, all EU member states had to submit draft NECPs for the period from 2021 to 2030 – documents, which “outline how EU countries intend to address the 5 dimensions of the energy union: decarbonisation, energy efficiency, energy security, internal energy market, research, innovation and competitiveness.” (European Commission 2023), 5We recognise that some institutions combine climate mitigation and climate adaption (e.g. the UK CCC includes an Adaptation (Sub-)Committee). We nevertheless include these institutions because they retain a focus on climate mitigation., 6Unlike the German Bürgerrat Klima, this citizens’ assembly would qualify as a state institution since it was run by the House of Commons (Climate Assembly UK n.d.).

Clearly, this definition – with its focus on formal, state climate mitigation institutions – is narrow, in comparison to other definitions in the literature. It certainly does not include all institutions that are influential in the climate policymaking process, such as think tanks and NGOs (e.g. Oreskes and Conway 2010; Wilkinson 2020; Böhler, Hanegraaff, and Schulze 2022), energy regulators (e.g. Ofgem in the UK, Australian Renewable Energy Agency) and other sector-specific institutions (e.g. rail and road transport infrastructure regulators), peak business associations or labour unions (e.g. Mildenberger 2020).

The rationale behind this narrow scope is twofold. First, most studies adopt broad definitions of climate institutions, including both formal and informal ones, without providing clear and straightforwardly replicable criteria for operationalising these definitions for comparative purposes. In contrast, our definition’s emphasis on formal institutions ensures a high degree of reproducibility, thus facilitating comparative analysis. Second, by carving out one segment of the set of climate-relevant institutions, we can reduce complexity and better disentangle the effects of formal, national, mitigation-focused institutions, and the effects of other institutions (e.g. sector-based, sub-national, informal). Both rationales are important for building the broader research agenda in this area, to expand our analysis to a greater number of country cases in future work, and to investigate the effects of other categories of climate-relevant institutions.

Finally, we operationalise our definition in a here-and-now manner by deliberately restricting our attention to a specific point in time (early 2023). As a result, we do not chart the emergence or development of institutions over time – nor do we examine temporal heterogeneity in the effects of climate institutions. We hope this will be the focus of future work, and we believe our static approach lays the groundwork for such a dynamic extension of our analysis. Yet, such longitudinal analysis is beyond the scope of this report.

2.2 Case selection

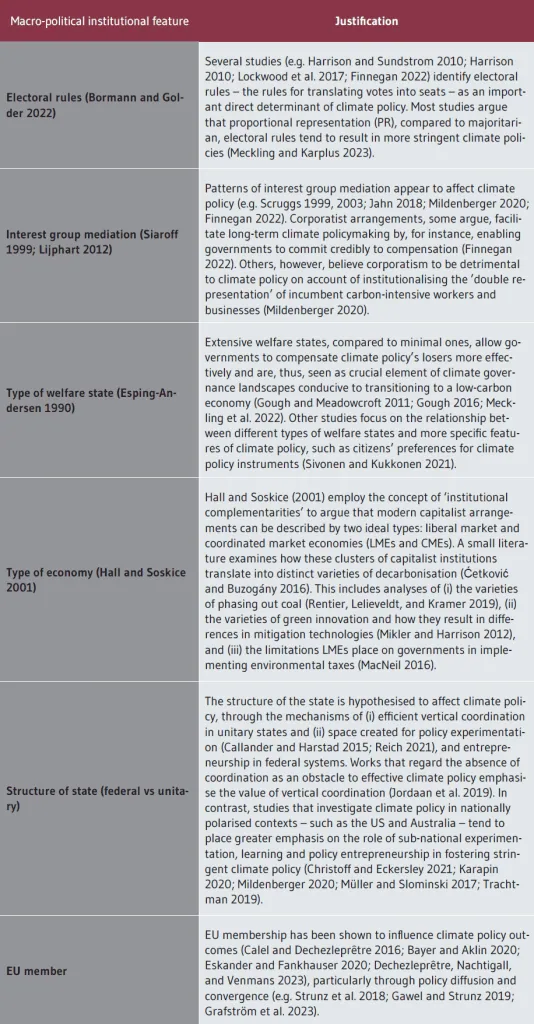

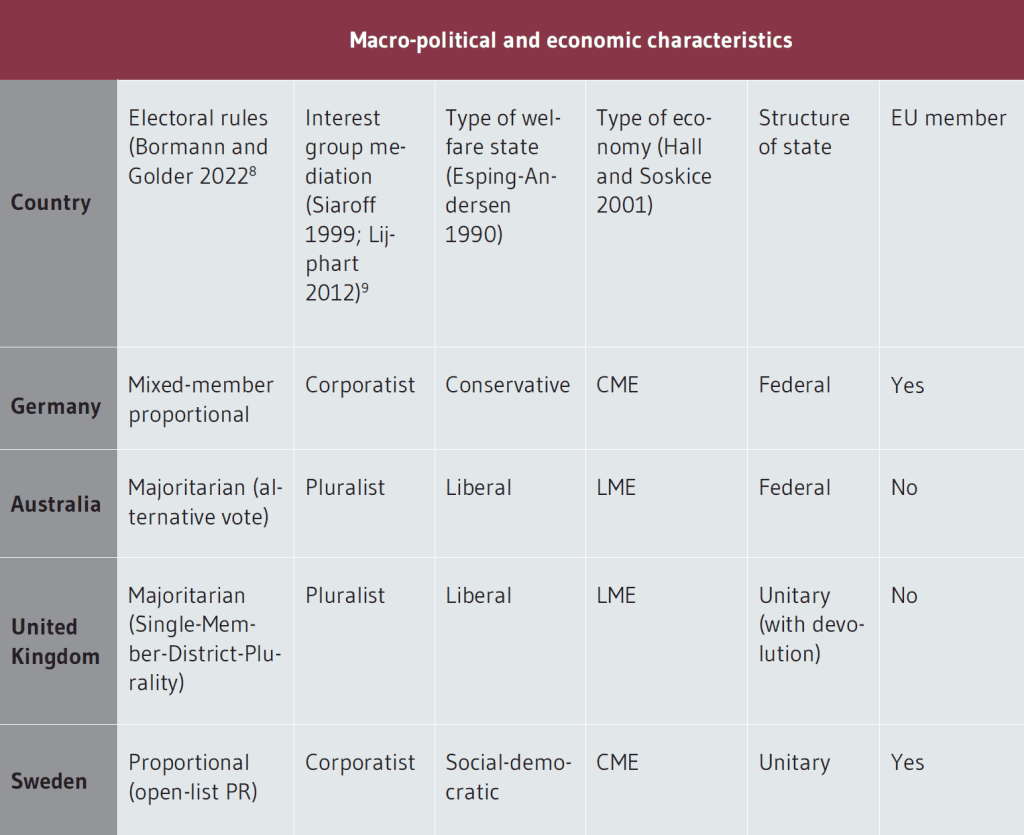

The sample of cases for our study are Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Given that we seek to establish a clear definition of climate institutions and facilitate theory building about their effects, our first criterion was to select countries that display relatively advanced development of these institutions. We then took the German case as our point of departure and selected three further cases that are socio-economically similar to Germany but differ in their macro-political institutions and features; specifically electoral rules, interest-group mediation, type of economy, structure of the state, and (non-)membership in the European Union (see Table 2).

This strategy – minimising variation in socio-economic characteristics while maximising variation in political institutions among countries with well-developed climate institutions – has three advantages relative to a most-similar approach. First, a diverse set of cases allows us to distinguish between features and functions of climate institutions that are unique to a given country and those that are common across different political contexts. Without the backdrop provided by politically different countries, we may mistakenly believe some idiosyncratic features to be general and vice versa. By reducing the risk of such misclassifications, a diverse case selection strategy is conducive to identifying necessary conditions and therefore to developing a clear definition.

Second, we know that climate institutions can affect policymaking differently in different contexts. This can be as a result of their varying functions (i.e. what they are mandated to do) or because there are ‘intervening variables’ – such as electoral rules, or political culture – that change the effect of institutions. Examining macro-politically different cases helps us to illuminate these distinct sources of variation, which is important for accurately identifying variation in the effects of otherwise similar climate institutions.

Thirdly, diverse cases enable us to investigate whether and how different macro-political contexts give rise to distinct clusters of climate institutions (Guy, Shears, and Meckling 2023); this allows researchers to clearly specify the scope conditions of their hypotheses as to what effects different climate institutions have on the policymaking process. Though clearly, more cases are needed to define these clusters, our case selection approach aids hypothesis generation in this way and provides a foundation for future research.

We varied our cases based on macro-political institutional variables identified in the climate policy literature as potential drivers of both intermediate (aspects of climate policymaking, see section 1) and ultimate policy outcomes (e.g. stringency of targets and instruments). Table 2 provides a justification for each of these variables and Table 3 summarises how they vary across our chosen cases. It is worth noting that these macro-political variables are correlated with one another, giving rise to multi-collinearity between them. The resulting clustering of macro-political institutions is one reason why it is empirically difficult to disentangle the effect(s) of one type of institution, e.g. electoral rules, on climate policy outcomes.7 We thank Marion Dumas for pointing this out.

8We classified electoral systems according to the ‘elecrule’ variable in Bormann and Golder (2020, 7). While we recognise the importance of all three components of electoral systems – ballot structure, district magnitude, and electoral rules (Cox 1997; Shugart and Taagepera 2017) – we focus only on the third component because it features most prominently in the relevant literature.,9 Countries’ interest group systems were classified based on Lijphart’s extension of Siaroff’s ‘index of interest group pluralism’, which ranges from 0.35 (Sweden) to 3.25 (Canada). The mean is roughly 2.02 and the standard deviation is 0.95. Given that Australia (2.12) and the UK (3.02) have above-average pluralism scores, we classify their interest group systems as pluralist, and because Germany (0.88) and Sweden (0.35) have below-average scores we classify them as corporatist.

Economically, both Sweden and Germany belong to the group of coordinated market economies (CMEs), and, as such, tend to rely on corporatist structures for interest group mediation. While, politically, both countries use proportional representation (PR) electoral systems, there are important institutional differences, notably Sweden being a unitary state and Germany being a federal one. In contrast, the two Anglo-Saxon countries in our sample have liberal market economies (LMEs) and pluralist interest group systems. Politically, they both elect their representatives via majoritarian electoral systems, though they differ in the structure of their states, with the UK being unitary and Australia being federal.

2.3 Literature review

To develop our analytical framework, we conducted a two-part literature review: (1) a scoping review of the literature to identify the range of approaches used to analyse political institutions and their effects on climate policymaking, and (2) a focused review of papers that specifically examine the effects of climate institutions. Each is discussed in turn, below.

2.3.1 Review of existing approaches to analysing the effects of institutions on climate policymaking

We conducted a scoping review of the literature to understand the effects institutions have been shown to have on climate policymaking, and to find out whether there were existing analytical approaches or frameworks that we could apply to climate institutions. To that end, we reviewed frameworks about the role of institutions from the broader political science, comparative politics, and policy studies literatures. In addition, we also reviewed literature on the effects of institutions on climate policymaking, broadly defined. Given the large and broad range of relevant material, it was not possible to conduct this review exhaustively – instead, we identified papers drawing on relevant syllabi and identifying related papers using Google Scholar and Research Rabbit.

The outcome of this literature review was two-fold. First, we ascertained that no appropriate frameworks exist for analysing the impact of climate institutions, emphasising the need for a novel framework. Second, we identified relevant macro-political institutions for variation in case selection (see Section 2.2).

2.3.2 Review of effects of climate institutions on climate policymaking

Our second step in the literature review was to narrow our focus to studies that examine the functions and effects of climate institutions. We wanted to capture the range of effects identified in the literature, to help us answer our second research question: what impact do institutions have on climate policymaking? This presented us with two challenges: one conceptual, the other technical.

Conceptually, the main challenge was that the existing literature relies on vague and hard-to-operationalise definitions of ‘climate institutions’. This implied that we could not simply identify relevant papers by searching for a clearly specified list of climate institutions. Drawing up such a list a priori carried the risk of overlooking important climate institutions and the literatures relating to them. To avoid these pitfalls, we scoured the academic literature via Scopus and ResearchRabbit for a broad range of keywords, from ‘climate advisory body’ to ‘consultation venue’.10The exact Scopus query was: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“Climate” OR “climate”) AND (“council” or “advisory body” OR “framework law” OR “legislation” OR “act” OR “ministry” OR “department” OR “committee” OR “governance” OR “consultation venue” OR “inter-departmental coordination” OR “strategy”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “SOCI”)).

The technical challenge was to prune the just over 31,000 papers our search returned to those focused on climate institutions. To that effect, we downloaded the Scopus query as a csv file, and followed the conventional approach to topic modelling by fitting a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model to the paper titles (Grimmer, Roberts, and Stewart 2022). The number of topics (twelve) was chosen by trial and error to allow for a maximally efficient manual search of our query’s results. Ultimately, we identified roughly 130 papers on climate institutions for advanced industrial democracies (see section 2.2).

To identify the papers focused specifically on the effects of climate institutions (rather than, for instance, on their emergence), we developed four scoping rules. These scoping rules were particularly important for dealing transparently with borderline papers – papers not clearly focused on climate institutions’ effects, but whose results are potentially relevant for understanding these effects. Our four scoping rules were:

- The independent variable is a climate institution in one of our sample’s four countries, or in a country similar11We define ‘similar’ as a democracy, with similar GDP per capita that is also part of the same region (Western Europe, Nordic region, Central Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, South-East Europe, Asia-Pacific region). to the countries in our sample.

- The dependent variable is related to climate policymaking, which we define as the process of formulating, coordinating, deciding, and implementing national climate policy.

- The climate institution examined in the paper meets all of the seven definitional conditions that we rely on for operationalising ‘climate institutions.’ These are: state, formal, national, climate mitigation-focused, encompassing, permanent, steering (see Table 1).

- The effect of the climate institution is identified empirically OR the effect is theorised ex-ante (i.e. the effects are hypothesised, as opposed to actually identified). We include the additional ex-ante criterion to widen our sample slightly, given the very limited number of papers examining actual effects.

Applying these scoping rules left us with a sample of just over 30 papers. To analyse these papers, we devised a coding scheme, which required coders to specify (i) the climate institution having the effect, (ii) the hypothesised effects or theory, (iii) the mechanisms bringing about the effects, (iv) the actual effects, and (v) the dependent variable.12If possible, coders were required to specify the dependent variable at a conceptual level, how the paper operationalises the dependent variable, and the data used for operationalisation. We randomly assigned two coders to each paper, who first blind-coded the paper before comparing their results with the other to ensure inter-coder reliability. Based on the coding scheme, coders’ classifications of the relevant papers were mostly aligned. When disagreements arose, a third coder was consulted to resolve these.

We used the results of this coding exercise to identify effects of climate institutions in our comparative analysis and to estimate ‘confidence levels’ for those effects (see section 4.3.2).

2.4 Empirical analysis

The goal of our empirical analysis was to identify and compare the climate institutions in each of our selected countries, their key features, and effects. This analysis consisted of two parts: a desktop review of climate institutions drawing on public documents, and interviews with experts in climate policy.

2.4.1 Desktop analysis

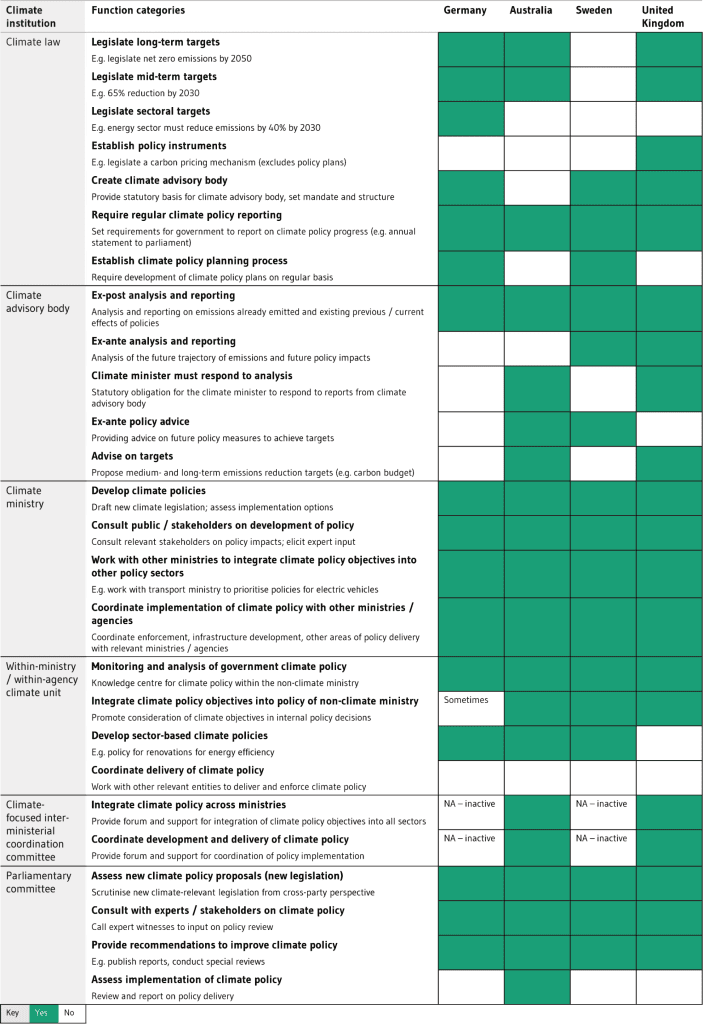

For our desktop review, we created a matrix of climate institutions, their features, and functions, with ‘features’ referring to important descriptive characteristics of climate institutions (e.g. size and composition of climate advisory bodies) and ‘functions’ referring to what the respective institutions are intended do13While we recognise that institutions cannot be doers without agents, we use this expression as a shorthand, reflecting our assumption that institutions are a means through which agents pursue their strategic objectives. in the climate policymaking process. Our initial categories of institutions were based on the climate institutions present in the German case. This reflected our orientation towards and stronger understanding of the German climate governance landscape. We then identified the corresponding institutions in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Australia, noting where there were gaps compared with Germany and adding categories of institutions identified in other cases. We drew on primary documents, including legislation and policy documents, as well as secondary sources, like academic articles and media reporting. This exercise produced a broad mix of institutions across the four cases.

Based on this analysis of ‘climate institutions’ across our four cases, we developed seven definitional ‘criteria’ that any institution must collectively meet to qualify as a ‘climate institution’ (see section 2.1). We then excluded institutions that do not meet our definition to produce a final, harmonised list.

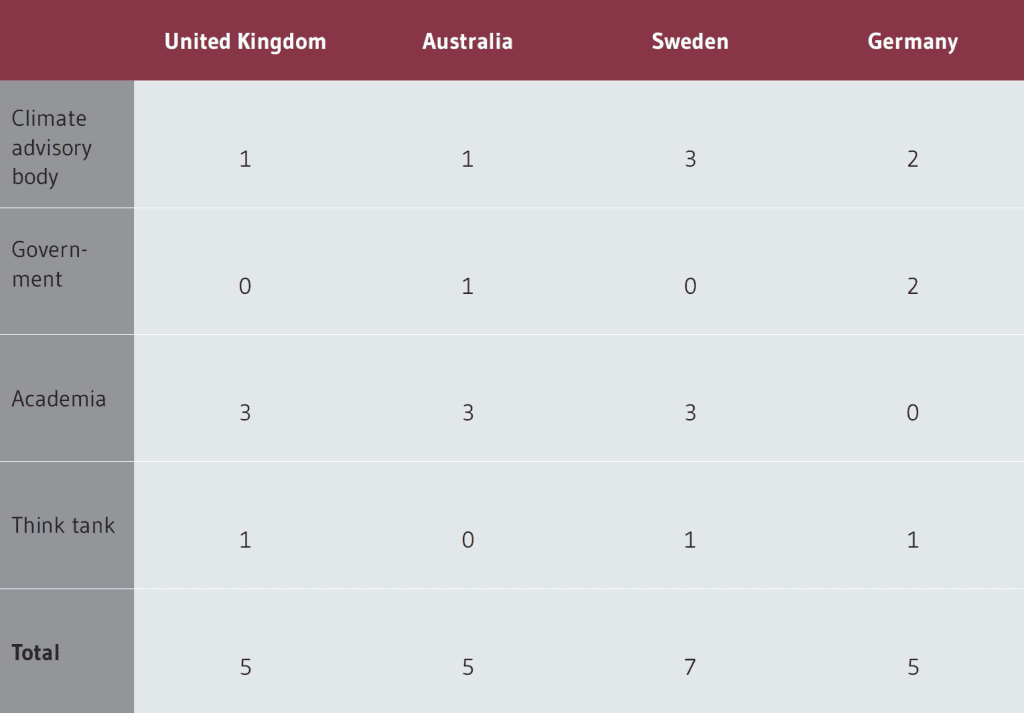

2.4.2 Interviews

The purpose of interviews with climate policy experts across the different countries was (1) to test our list of climate institutions and identify any further institutions we might have missed, (2) to better understand the functions of these institutions in the climate policymaking process, and (3) to identify hypothesised effects of these institutions from the perspective of interviewees. We conducted 22, roughly one-hour interviews14All interviews, save for one, were conducted in English. in total, including five in Germany, seven in Sweden, five in the United Kingdom, and five in Australia. Our full list of interviewees is contained in the appendix. We asked interviewees the same types of questions across all countries (refer appendix for generic questionnaire), and included a tailored list of climate institutions, based on our definitional criteria (see section 2.1). We discussed each institution in turn with our interviewees to elicit their views on the functions of the institutions and their effects on climate policymaking.

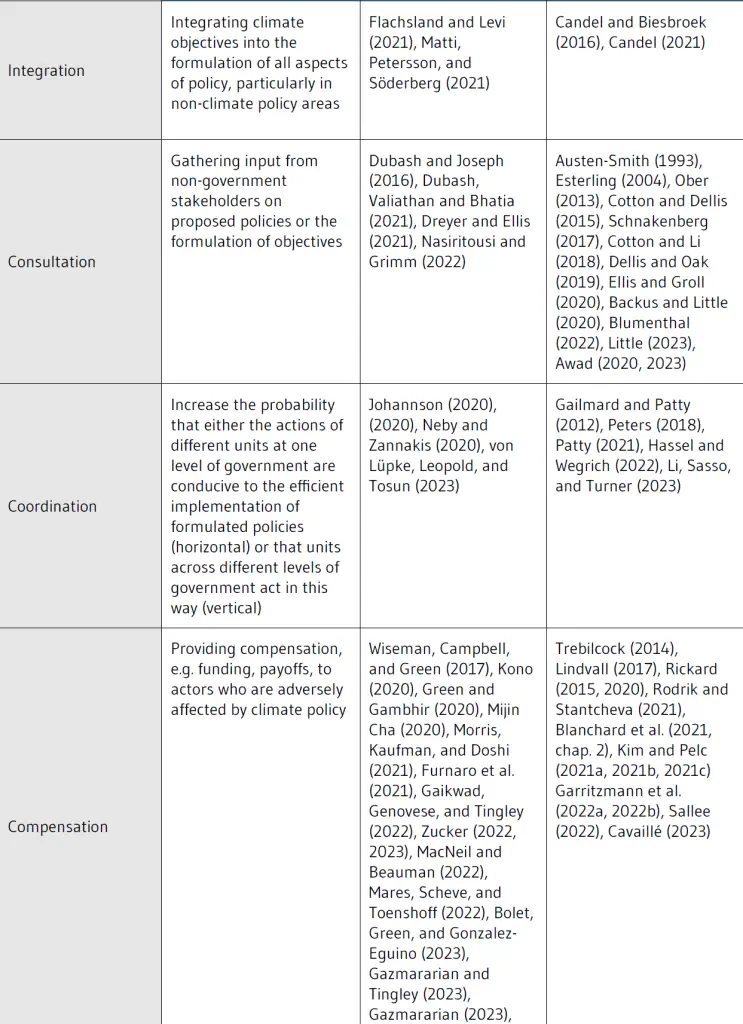

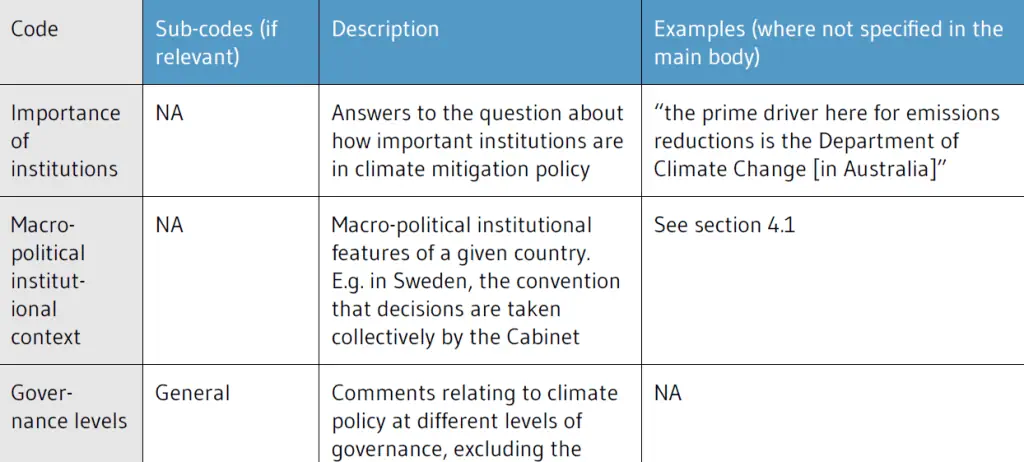

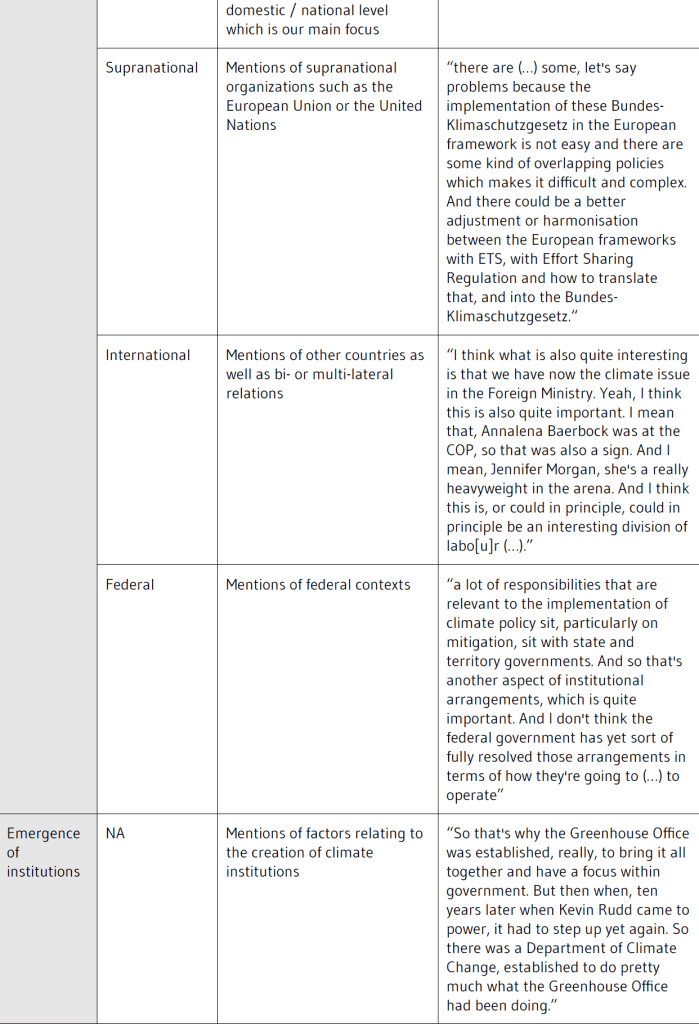

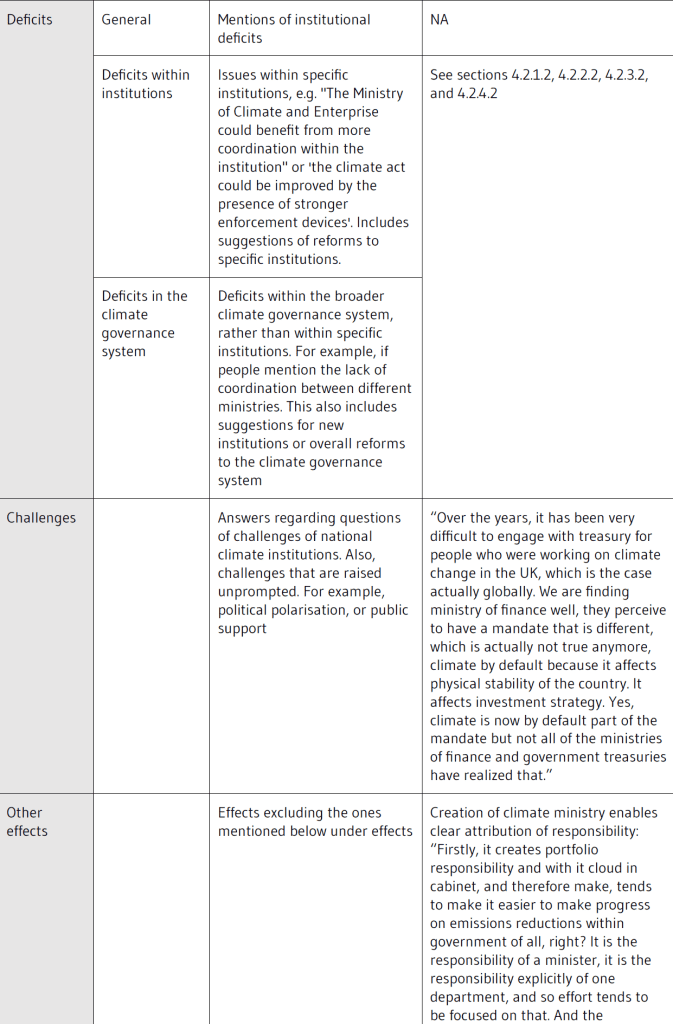

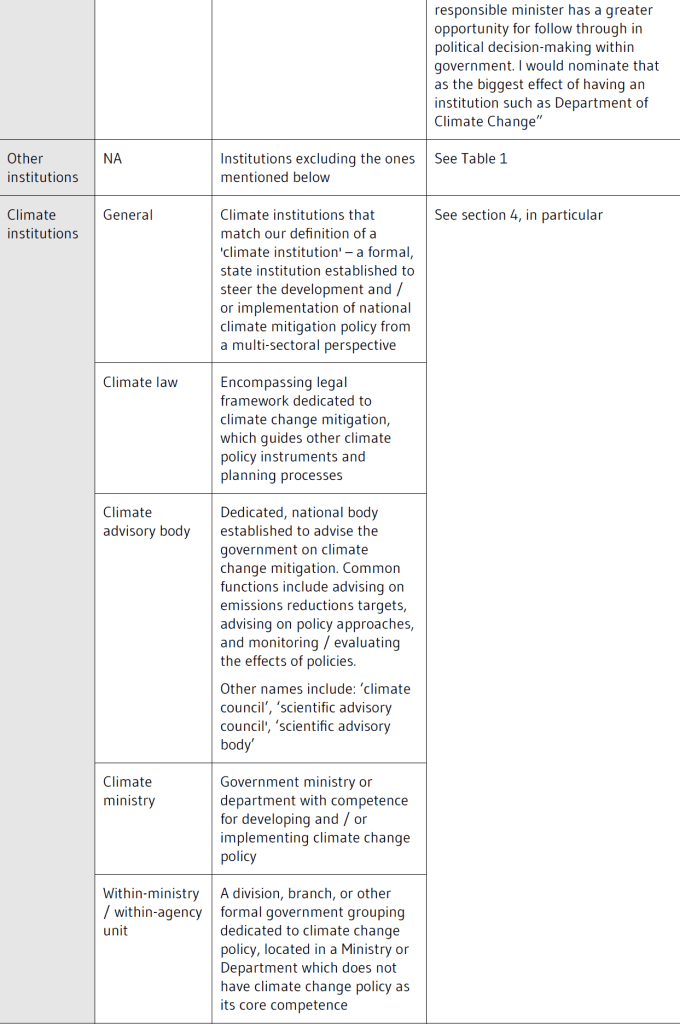

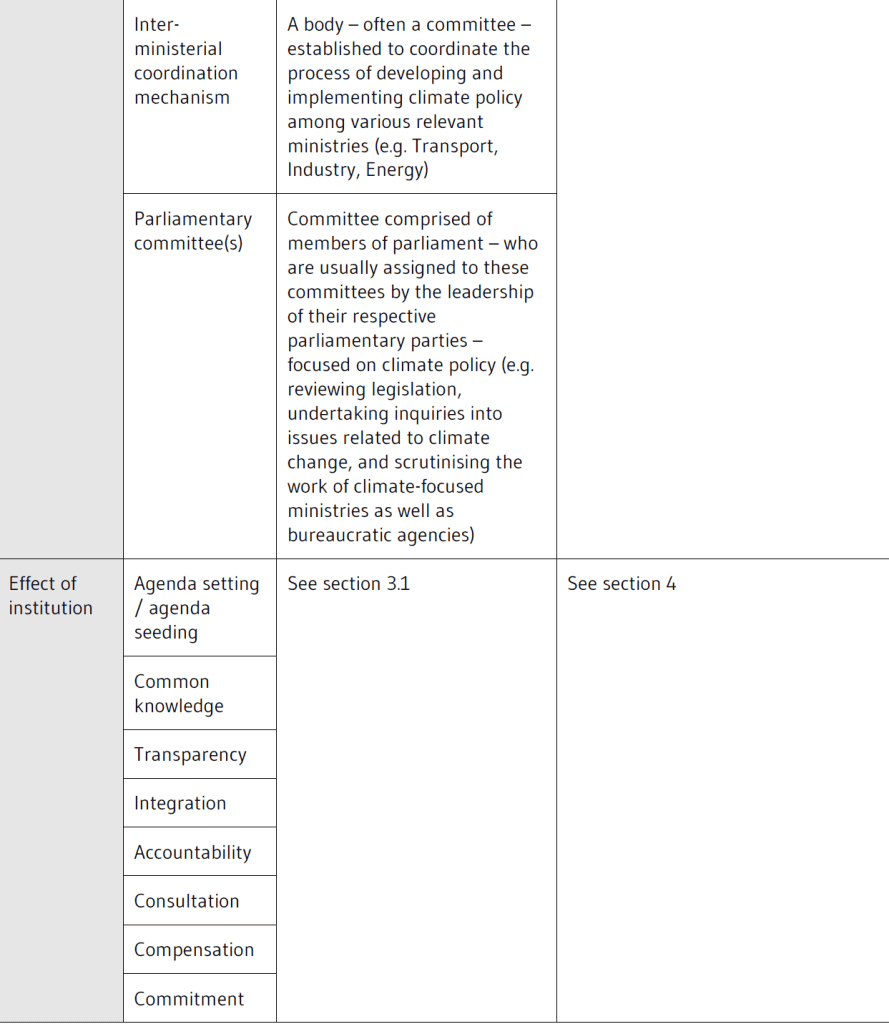

We coded interview transcripts in the qualitative analysis software MAXQDA. Our codebook consisted of two main elements: (i) the set of climate institutions included in our definition and (ii) the list of ‘strategic challenges in climate policymaking’ identified in our analytical framework (see section 3.1). Our full codebook is included in the appendix. This code system allowed us to identify matrices comprised of specific types of institutions (rows) and their effects (columns), which we used to draw comparative insights on the effects of institutions. A sample of five transcripts was double-coded to ensure inter-coder reliability, which averaged approximately 70%.

After completing our first full draft of the report in early June 2023, we conducted a two-step review process. First, we shared the draft with all our interviewees to ensure they were happy with how we used their data in the report and to invite them to give substantive feedback if they wished. Second, as part of the internal Ariadne peer review process, we shared the draft version of the report with two, primary reviewers. We also circulated the report among roughly 15 climate policy experts to elicit additional feedback. Given the urgency of the debate about German climate institutions and the Klimaschutznovelle, we told experts that we could only incorporate feedback received by late June. In addition to the comments by our two primary reviewers, we received comments by five other experts. We responded to these comments by creating an excel sheet, indicating the section to which a given comment pertains, the comment itself, our decision as to whether we accepted or rejected the comment, and our reason(s) for doing so.

2.5 Identifying reform options

The final step in our process was to draw on the results of our comparative analysis to identify gaps in the landscape of German climate institutions and potential avenues for reform.

The rationale for doing this was twofold. First, the goal of the Ariadne research project, of which this report is a part, is to guide the German government through the energy transition (Ariadne n.d.). As a result, we seek to illustrate the policy relevance of our findings by shedding light on institutional reforms that may enable or constrain Germany’s path to climate neutrality. Second, we want to demonstrate how our framework can be used as a diagnostic tool to identify institutional gaps and propose reform options based on analysis of climate institutions in other countries.

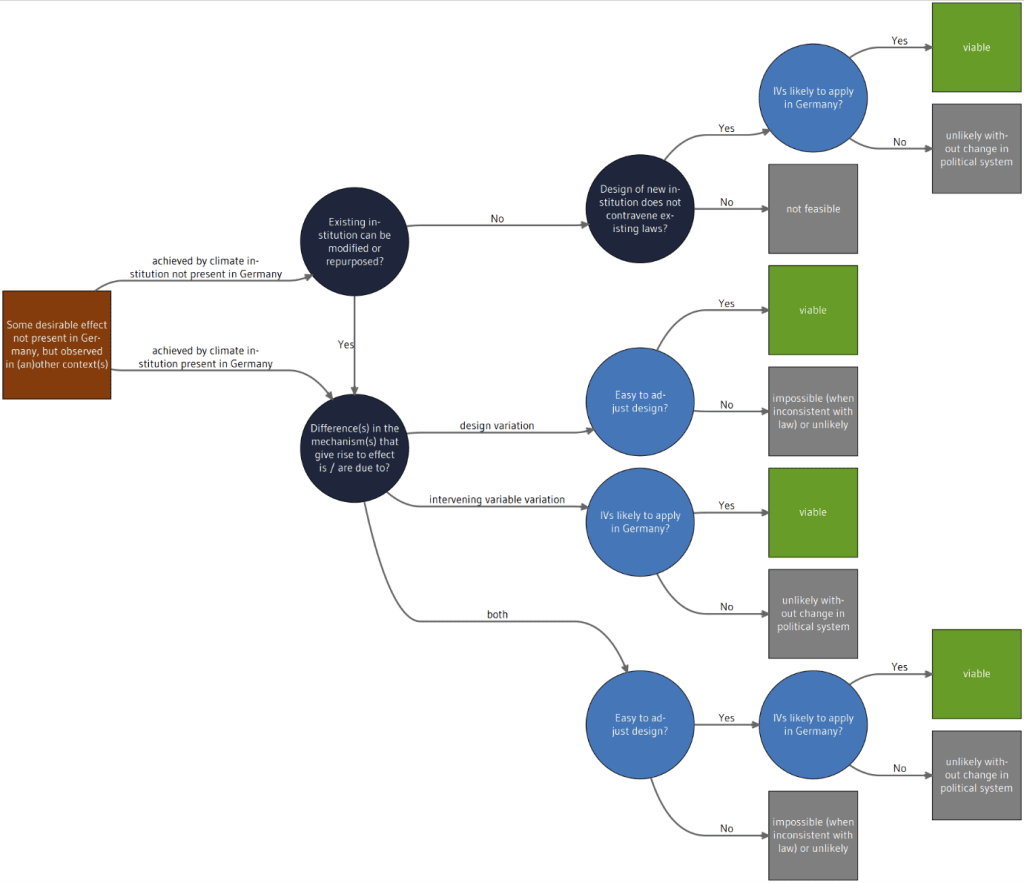

The ’strategic challenges’ aspect of our analytical framework (see section 3.1, below) reveals gaps – strategic challenges that the ensemble of German climate institutions currently does not address, or addresses only insufficiently – and therefore helps identify institutional deficits. The ‘stylised causal chains’ aspect of our analytical framework, with its focus on mechanisms, allows us to leverage our comparative analysis to identify where institutional innovations may be replicated across contexts. Rather than adopting a simple copy-and-paste logic, we identify where mechanisms driving the effect(s) engendered by an institution might carry over to the German context. For a more detailed description of this methodological approach, refer to Appendix.

During the writing of this report, the German government published a draft proposal to considerably amend the KSG via the Klimaschutznovelle. The proposed changes have potentially profound implications for German climate governance and the functioning of German climate institutions. Given our analysis was conducted prior to the amendment, we do not analyse these changes in our main results. In section 5, however, we draw on these results to analyse which institutional gaps the Klimaschutznovelle may fill and what deficits remain. The reform options we outline take the proposed amendment into account – we identify further potential reforms to ensure the updated German climate governance framework can function effectively.

3. Analytical Framework

Drawing on our literature reviews (see section 2.3), we devised an analytical framework that allows us to identify what effects climate institutions have on the climate policymaking process and how these effects are engendered. Our framework’s two central planks are:

- strategic challenges present in climate policymaking (discussed in section 3.1), and

- stylised causal chains connecting climate institutions to their effects on policymaking, via addressing related strategic challenges (discussed in section 3.2).

Climate change is a deeply challenging policy problem for several reasons. It is characterized by severe or ‘deep’ uncertainty (Kriegler et al. 2009; Held et al. 2009; Weitzman 2009; Schmidt et al. 2011, 2013; Nordhaus 2013; Weitzman 2015; Wagner and Weitzman 2015; Barnett, Brock, and Hansen 2020; Manski, Sanstad, and DeCanio 2021; DeCanio, Manski, and Sanstad 2022; Fillon, Guivarch, and Taconet 2023) – both about the physical impacts of climate change (including their temporal and spatial distribution), and about the efficacy of potential policy instruments to mitigate dangerous climate change. It demands long-term investments, which impose costs on individuals, communities and businesses in the present for payoffs (far) in the future. Climate policy faces significant barriers to implementation, including the physical challenge of replacing or ‘greening’ fossil fuel infrastructure, and political barriers from interest groups who stand to lose in the transition. These ‘wicked’ features of climate policy imply a series of ‘strategic’ challenges. They include the need to build a shared understanding of the problem of climate change and potential solutions, the need to ensure long-term commitment to emissions reductions targets, the need to compensate losers, and the need to coordinate activity across all sectors of the economy and segments of society more broadly. These challenges appear throughout the policy process and addressing them supports ambitious domestic climate action.

Our analytical framework, as summarised in Figure 3, begins with the assumption – following, inter alia, Averchenkova and Nachmany (2017) and MacNeil (2021) – that institutions represent a means to respond to these strategic challenges. A classic response to the challenge of commitment, for example, is to delegate policy decisions to independent institutions (Gilardi 2002), like a central bank or a climate advisory body, to insulate them from short-term political, especially electoral, pressures (Brunner, Flachsland, and Marschinski 2012). We represent this assumption in the figure below with the arrow connecting ‘strategic challenges’ to the institutional ecosystem box. Institutions, however, are not the only means by which policymakers respond to these challenges. Policy instruments, the regulatory toolkit upon which governments draw, and targets, can all also address strategic challenges. For example, both policy instruments and targets can be designed in ways to encourage commitment. This can be achieved by, inter alia, including a price collar in the design of an emissions trading scheme (Edenhofer et al. 2019; Stavins 2022), adopting earmarking rules for revenues from environmental taxes (Marsiliani and Renstrom 2000), creating enforceable property rights to investment subsidies (Abrego and Perroni 2002) or carving long-term targets into five-year carbon budgets. Responding to strategic challenges via instruments15See, for instance, the work by Fernández-I-Marín, Knill, and Steinebach (2021). or targets, however, is not the focus of our study.

The second part of our analytical framework, in the centre of Figure 3, is the ‘stylised causal chain’ through which climate institutions engender effects via addressing strategic challenges. This causal chain consists of an institution’s function (what it is intended to do), the mechanism by which (how) an effect is engendered, an intervening variable which influences the effect, and the effect on a strategic challenge (e.g. achieving commitment). The arrow connecting ‘effect on strategic challenge’ to ‘effect on climate policy’ illustrates that tackling these strategic challenges institutionally can influence policy, including targets, the choice of policy instruments, and their stringency.

Source: Own illustration.

We also indicate that institutions can have other, independent effects (the ‘other effects’ box), such as improving the government’s credibility in international negotiations (e.g. Bennett 2018), changing decentralised agents’ investment behaviour via changing investors’ expectations (e.g. Dorsey 2019), or giving rise to policy diffusion (Torney 2017, 2019). ‘Other effects’ can in turn affect overall stringency, as shown by the arrow between ‘other effects’ and the ‘effect on policy’ box. Our framework focuses on the effects of climate institutions but recognises that these are part of a broader set of institutions, identified in the ‘other institutions’ box. Naturally, other institutions, such as informal climate institutions and non-climate institutions, can also affect policy, as indicated by the arrow connecting ‘other institutions’ to ‘effects on policy’. The solid arrows indicate relationships we are interested in for the purposes of this study; the broken lines indicate other relationships which we do not explore.

Before setting out this analytical framework in more detail, three caveats are required. First, our challenge-focused approach carries the risk of being ‘hyper-intentional’ – assuming that institutions are intentionally created by rational, forward-looking actors to help them solve complex strategic challenges. While institutions can be intentionally created to address strategic challenges, clearly this is not always the case. Assuming this would be at odds with important strands in the broader political science literature – including historical-institutionalist analyses of the emergence of institutions (Mahoney and Thelen 2009), the ‘policy drift’ and path-dependence literatures (Page 2005; Hacker and Pierson 2010; Callander and Krehbiel 2014; Galvin and Hacker 2020) – which highlight the importance of, for instance, misperceptions and unintended consequences in institutions’ effects (Pierson 2000; Cortell and Peterson 2001). To reduce the risk of hyper-intentionality, we carefully distinguish between the functions of institutions – what they are intended to do – and their actual effects.

Second, our analytical framework does not assume that climate institutions are always the most effective means of addressing strategic challenges and therefore that countries will only be able to address the strategic challenges outlined below (see section 3.1) by adopting the full range of climate institutions we analyse in section 4. Our framework rather acknowledges that other (types of) institutions, e.g. informal institutions, or non-institutional means, such as policy instruments, may better address some challenges and that this will likely vary across (macro-political) contexts. Understanding which strategic challenges are best addressed by formal, mitigation-focused climate institutions, as opposed to policy instruments or other types of institutions, is a potential avenue for further research.

Finally, our framework is designed to capture effects at a specific point in time, not to explain the emergence of institutions over time. Other frameworks – such as historical institutionalist ones – may be more appropriate for this analysis. There is potential to extend our framework, however, for future longitudinal analysis by comparing effects and mechanisms both across time and countries.

3.1 Strategic challenges

Operationalising our ‘functionalist’ analytical approach – i.e. conceiving of climate institutions as a means through which policymakers respond to strategic challenges – requires a list of such challenges. Ideally, we would derive this list from an encompassing theory of (climate) policymaking, which provides micro-foundations for the relevant challenges. This means generating a list of strategic challenges based on systematic analysis of how political actors achieve climate policy goals. Yet, to our knowledge, there exists no theoretical framework – neither in the broader political science literature nor in the ‘effects of climate institutions’ literature – that allows us to derive a list of strategic challenges in this way. The policy cycle framework (Guy, Shears, and Meckling 2023) helps to distinguish between different activities in the policymaking process, but, because of its static nature, fails to capture challenges that appear dynamically across cycles. This is particularly problematic for analysing climate policy since much of it is about achieving long-term policy goals across multiple policy cycles (e.g. Brunner, Flachsland, and Marschinski 2012).

We therefore derive our list of strategic challenges inductively from the scoping review of the broader political science literature on the role of institutions (see section 2.3.1) and validate it based on our analysis of the ‘effects of climate institutions’ literature (see section 2.3.2). The resulting list serves as a heuristic – rather than an exhaustive and definitive list of strategic challenges present in climate policymaking. Indeed, deriving such a list from first principles is an important avenue for future research. Despite that, we believe our list of strategic challenges to be good enough for our descriptive and comparative purposes: the list is both sufficiently broad for us to be able to investigate the effects of climate institutions on multiple important aspects of climate policymaking and sufficiently generalisable across contexts to allow for comparative analysis of these effects.

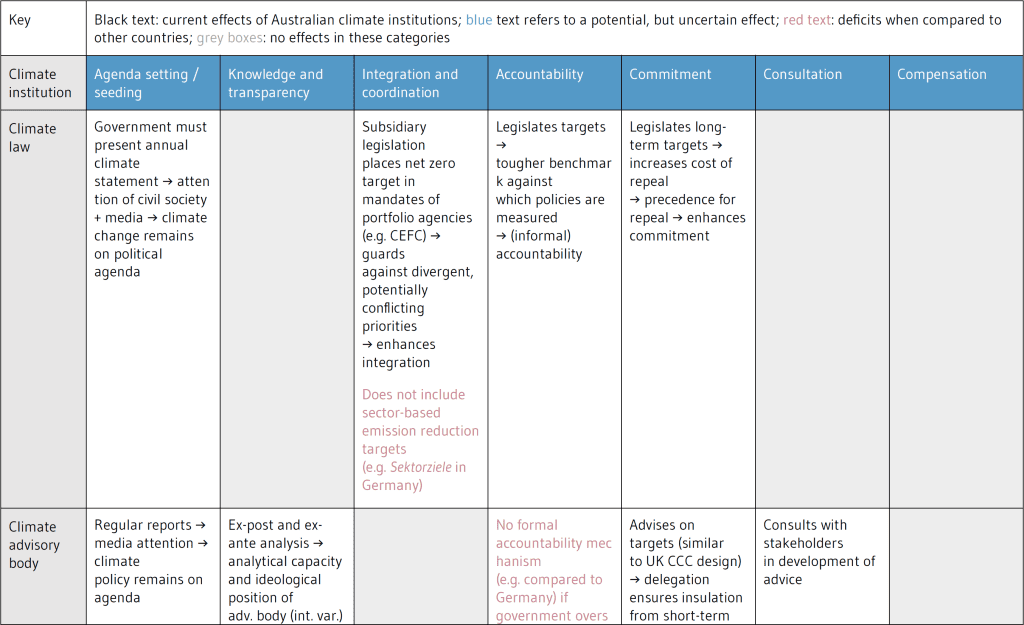

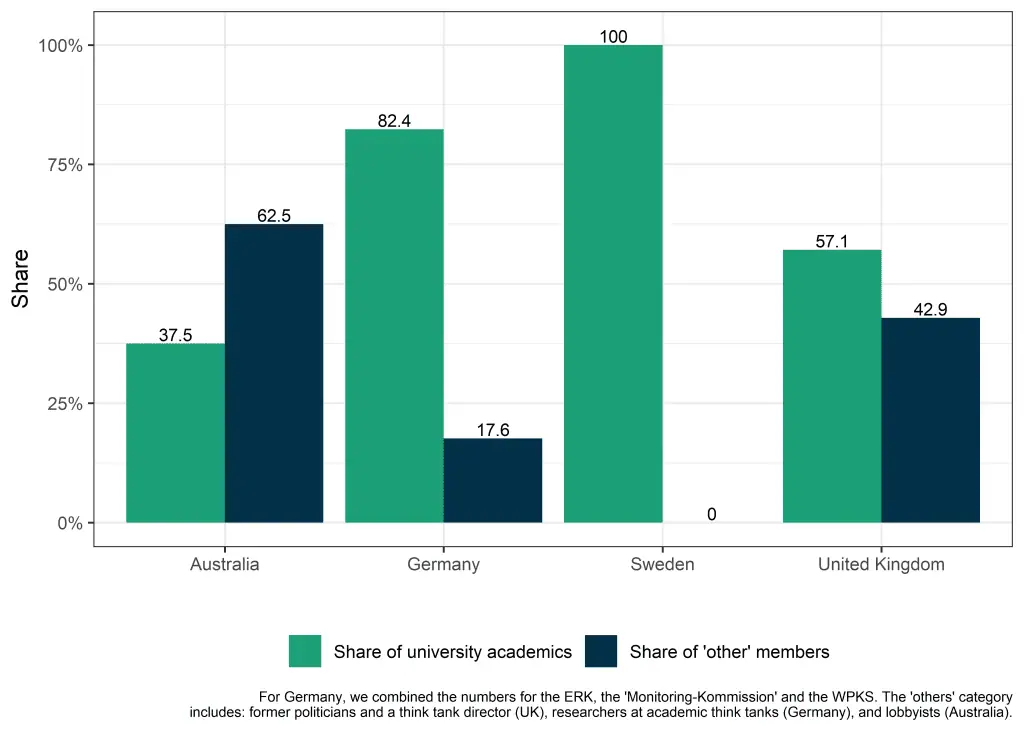

The strategic challenges most salient in the ‘effects of climate institutions’ literature are visualised in the word cloud above (see Figure 4), which is based on our coding of the ‘effects of climate institutions’ literature (see section 2.3.2). Since our primary objective is to conduct comparative analysis, we focus our attention on challenges that are likely to be common across contexts, though we understand their specific features will vary between countries. Overall, we identified eight strategic challenges present in climate policymaking that climate institutions may help to address. Each is defined briefly below.

Source: Own illustration.

Agenda seeding & setting: Agenda seeding (Wasow 2020) is an attention-related challenge that here refers to the ways in which climate institutions seed ideas about climate policy in public and / or elite discourse, for instance by suggesting new policy instruments or new frameworks for thinking about climate policy.16The Stern Review, for example, popularised the use of cost-benefit analysis for justifying climate targets, as is borne out by its headline conclusion that the costs of inaction on climate change exceed the costs of action (Stern 2007). The recently published Skidmore Review follows a similar logic in making the case for the UK’s net zero target (Skidmore 2023, pt. 1). Agenda setting,17Our definition is narrower than other definitions in the literature, which frequently do not differentiate between agenda setting and seeding. Guy, Meckling and Shears (2023, 190), for example, define agenda setting as the way in which ‘the state comes to understand climate change as a policy problem and how it augments and rearranges its organs in response.’ in contrast, occurs when climate institutions (i) put climate policy on the political agenda, and / or (ii) increase the probability that it will remain on the agenda in the future. Both concepts are widely considered important, but there is little work on how they are affected by climate institutions. Guy, Meckling and Shears (2023) are a notable exception, arguing that climate framework laws, research bodies, and coordination bodies have an agenda-setting effect.

Knowledge and transparency: the epistemic or knowledge-related challenge of establishing common knowledge and providing transparency.

- Common knowledge: the problem of establishing a shared understanding of issues relevant to climate policy among policy elites (e.g. politicians, bureaucrats, journalists, private-sector actors) and creating an awareness among elites that this knowledge is shared by other elites, who, in turn, know or believe that others know and so on. Common knowledge includes key facts about the policy problem (e.g. the greenhouse effect), and the mechanisms as well as trade-offs underlying policy instrument choice (e.g. market-based vs. non-market-based). Our definition implies that common knowledge requires actors to coordinate their beliefs about these factual components of climate policy, i.e. they all agree on the credibility of information about these factual components (Basu 2018; Vanderschraaf and Sillari 2022). Common knowledge is crucial for enabling bargaining among elite actors and helping them reach consensus about policy decisions. To our knowledge, we are the first to introduce this strategic challenge in relation to climate institutions, though there is an extensive game-theoretic literature on common knowledge (Brandenburger and Dekel 1989; Geanakoplos 1992). Common knowledge provision via climate institutions is related to Pielke’s (2007) idea of knowledge brokerage: When climate advisory bodies act as knowledge brokers18“The defining characteristic of the honest broker of policy alternatives is an effort to expand (or at least clarify) the scope of choice for decision-making in a way that allows for the decision-maker to reduce choice based on his or her own preferences and values.” (Pielke 2007, 2) they can create common knowledge, as Averchenkova, Fankhauser, and Finnegan (2021b) show in the UK context.

We focus on common knowledge among elites, as opposed to the general public, because we conceive of this strategic challenge specifically in relation to climate institutions. Given the literatures (i) on low levels of political knowledge among the public (Bartels 2016; Achen and Bartels 2017; Illing 2017) and (ii) the long and complex processes required for mass-level common knowledge to emerge (e.g. Suk-Young Chwe 2013), it seems unlikely that climate institutions coordinate beliefs among citizens about the often highly specific aspects of climate policy these institutions deal with, like emissions reductions targets (e.g. five-year carbon budgets in the UK), potential policy instruments, and trade-offs between these instruments.

By adopting this elite-centred conception of common knowledge we do not wish to deny the importance of mass-level awareness of climate change and climate policy. Indeed, our elite-centred conception is compatible with climate institutions playing an important role in raising awareness of climate change and making information available to the public; we deal with this under the ‘external’ aspect of the strategic challenge of transparency. Such efforts aimed at increasing climate policy’s salience and / or disseminating information do not, however, amount to facilitating the emergence of mass-level common knowledge, which would require that these institutions are capable of coordinating beliefs among the public.

- Transparency: (i) increasing access to information about climate policymaking, including with respect to the scale of the problem (e.g. ex-ante emissions gap), existing and potential policies to address the problem, and the projected (ex-ante) as well as actual (ex-post) effectiveness of these policies, and (ii) synthesising information in an easily comprehensible manner, for instance by gathering data and creating new indicators.19A case in point are energy unit costs (‘Energiestückkosten’), the energy costs per unit of value added, which were first systemically measured in 2013 / 2014 by the “Monitoring-Kommission” to assess the industrial competitiveness of German sectors in comparative perspective (Germeshausen and Löschel 2015; Kaltenegger et al. 2017). Transparency can be internal – increasing access to this information within and among government entities – and external: increasing access to the public and key stakeholders. A given institution may increase both. Transparency is less restrictive than common knowledge, which requires not only access to easily comprehensible information, but also agreement between elite actors on the credibility of that information. The transparency-enhancing effects of climate institutions figure prominently in the climate policy literature, in particular in studies on climate laws (Duwe and Evans 2020) and advisory bodies (Weaver, Lötjönen, and Ollikainen 2019; Evans and Duwe 2021).

Integration: the integration of climate objectives into all aspects of policy, especially in non-climate policy areas (Candel 2021; Candel and Biesbroek 2016), such as industrial or transport policy, plus strategic integration of cross-sectoral policy packages to ensure coherence in their pursuit of GHG reduction targets. In our analysis of climate institutions, we focus on structures and processes that incentivise decision-makers to take into account multiple objectives, the trade-offs between them, and the externalities generated by different policy instruments – all relevant considerations for integrated climate policy. Integration can occur within (within-ministerial integration) or between ministries (cross-ministerial integration). In either case, integration often involves devising complex medium- to long-term policy plans, which requires substantial analytical capacity and bureaucratic expertise. Flachsland and Levi’s (2021) analysis of the German Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz’s effect on policy integration is an example of the nascent, integration-focused strand of the climate policy literature.

Coordination: creating and strengthening the institutions and mechanisms used to coordinate the development, monitoring, and delivery of climate policy such that state or governmental actors act in concert. Coordination can be horizontal among groups of actors (e.g. ministerial units) at one level of government, or vertical across different levels of government (Hassel and Wegrich 2022, chap. 8). Clarifying the assignment of responsibilities among state actors is a particularly important mechanism through which both vertical and horizontal coordination can be improved (Ting 2011; Gailmard and Patty 2012; Sasso, Turner, and Li 2020; Patty 2021; Hassel and Wegrich 2022, 141; Li, Sasso, and Turner 2023). Given our definitional criteria (see section 2.1), in this report we examine only horizontal coordination and distinguish between two sub-types. Horizontal coordination can occur within a single ministry (within-ministerial coordination), i.e. between the different entities (e.g. divisions or working groups) in a ministry, or between ministries (cross-ministerial coordination). Coordination is distinct from integration: the former relates to the process of policymaking, including its development and delivery, while the latter refers the substance of policy – how well integrated climate objectives are across policy packages. Coordination has long been recognised as a crucial strategic challenge in the public policy literature (Peters 2018; Coyle and Muhtar 2023), and recently also in the climate policy literature (Neby and Zannakis 2020; von Lüpke, Leopold, and Tosun 2023).

Accountability: holding the government responsible for delivering on its stated climate targets. Accountability implies both the existence of transparency and sanctioning devices of some kind, whether informal or formal. Informal sanctioning includes, for instance, the dismissal or demotion of ministers who fail to withstand parliamentary or media scrutiny on climate policy, or a loss of reputation. In contrast, formal sanctioning refers to legal challenges and other formal procedures used to punish non-compliance. Accountability is ex-ante when the government is (in)formally sanctioned before it has become clear whether it has achieved its targets. Otherwise, accountability is ex-post. The climate policy literature criticises the absence of sufficiently strong account-ability mechanisms for enforcing targets, though climate framework laws may function as informal and sometimes even formal accountability devices (Bennett 2018; Duwe and Evans 2020).

Commitment: requires policymakers to credibly indicate the long-term direction of climate policy. This implies giving businesses and the public confidence that changes in the distribution of political power will not lead the current government or future ones to renege on long-term climate commitments (policy reversal) and it is therefore safe to make the investments and behavioural changes necessary to achieve the government’s climate policy objectives. As a sizable body of work shows, governments can resort to a range of commitment devices, including delegation to independent bodies (Helm, Hepburn, and Mash 2003), legislation (Brunner, Flachsland, and Marschinski 2012), or (semi-) formal agreements between all major political parties (Lockwood 2021b). These commitment devices are formal when they incorporate explicit legal mechanisms for sanctioning governmental non-compliance, as is the case with some pieces of climate legislation, such as the German KSG’s Sofortprogramme following overshoot of Sektorziele (although note this mechanism will be removed under the amendment to the KSG, see section 5 for a discussion of this proposed change). Informal commitment devices, by contrast, rely merely on informal mechanisms for sanctioning non-compliance, such as reputational or audience costs.

Consultation: facilitating and structuring (Meckling and Nahm 2022; Srivastav and Rafaty 2023) discussions between government representatives and non-governmental stakeholders, including labour unions and businesses, about proposed targets or policies. Consultation is formal when the interactions between governmental and non-governmental actors occur in official settings, whereas informal consultation refers to unofficial exchanges. By gathering input from key stakeholders on policy proposals, consultation is an important means of interest group management – they help to manage the risk of interest groups lobbying against the adoption of legislation or undermining its implementation (Dubash and Joseph 2016; Pillai and Dubash 2021; Dubash, Valiathan, and Bhatia 2021). In addition, consultation allows stakeholders, with, for instance, sector-specific expertise, to communicate hard-to-find information to bureaucrats and politicians, which can improve the design and implementation of policies. Examples of consultation include Germany’s “Kohlekommision” and the Fossil Free Sweden initiative (Nasiritousi and Grimm 2022).

Compensation: compensating the losers from both climate policy, e.g. workers in carbon-intensive industries (e.g. UK CCC 2023a). The potential for compensation to ensure the ’buy-in’ of politically powerful actors and manage the influence of interest groups is a prominent theme in various strands of the broader political science (Trebilcock 2014; Lindvall 2017; Garritzmann et al. 2022a) and climate policy literatures (Green and Gambhir 2020; Finnegan 2022; Gaikwad, Genovese, and Tingley 2022; Meckling and Nahm 2022; Bolet, Green, and Gonzalez-Eguino 2023; Gazmararian 2023; Gazmararian and Tingley 2023; Srivastav and Rafaty 2023). Yet, few works examine how climate-related institutions affect the state’s ability to compensate losers so as to prevent them from undermining climate policy (Patashnik 2008) or even achieving cooperation from private actors threatened with losses, with important exceptions (Wiseman, Campbell, and Green 2017).

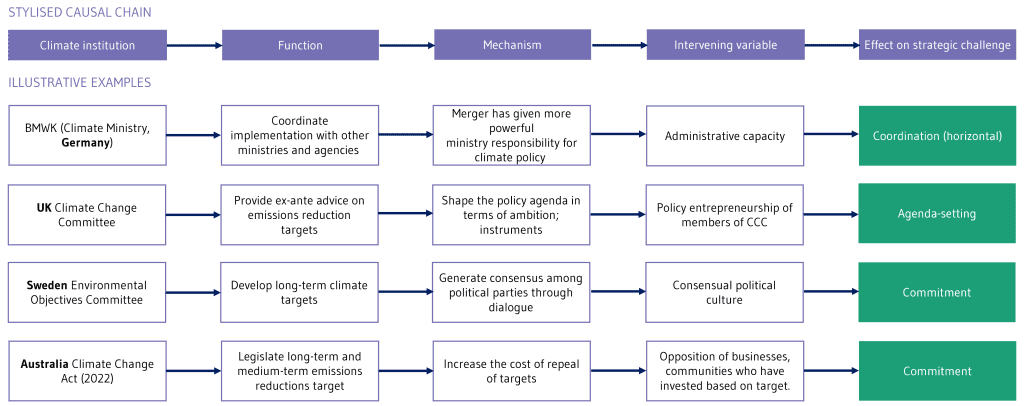

3.2 Stylised causal chains

Our framework aims to elucidate, in a stylised manner, the causal relationships connecting climate institutions to their effects on policymaking – the strategic challenges they address and how they do so. We do this by arranging five components – (i) institutions, (ii) functions, (iii) mechanisms, (iv) intervening variables, and (v) effects – into stylised causal chains, as shown in Figure 5. Functions relate to the strategic challenges that climate institutions are intended to address, as reflected in their respective mandates. Mechanisms describe the means by which (‘how’) climate institutions give rise to certain effects. Intervening variables capture the set of additional variables that influence the effect(s) of a given climate institution. The effect describes how the climate institution actually addresses one of the eight strategic challenges identified above.

Source: Own illustration.

The UK CCC example (top causal chain in Figure 5) illustrates how this framework allows us to identify effects of climate institutions, derived inductively from our analysis of interviews.20Given our relatively small number of interviewees and the semi-structured nature of the interviews, more work is clearly required to demonstrate the internal validity of our causal chains. We refer deliberately to these chains as ‘stylised’ because our method does not allow for causal identification. As discussed in section 4.2.2, the UK’s climate advisory body addresses the strategic challenge of agenda setting – putting pressure on the government to devote attention to climate targets and the policy mixes most conducive to achieving these targets. This effect can be traced back to three factors. First, its function: the UK CCC’s mandate includes the responsibility to provide ex-ante advice on emissions reduction targets via advice on five-year carbon budgets (McGregor, Kim Swales, and Winning 2012). Second, the effect’s mechanism: the UK CCC proposes carbon budgets that, in combination with past budgets, constitute a viable pathway to achieving the government’s stated long-term goal of carbon neutrality by 2045. Third, the central intervening variable is the policy entrepreneurship of the committee’s members – their willingness to be vocal in framing the committee’s recommendations as the benchmark for credible climate policy, i.e. policy that is consistent with the government’s long-term objectives.

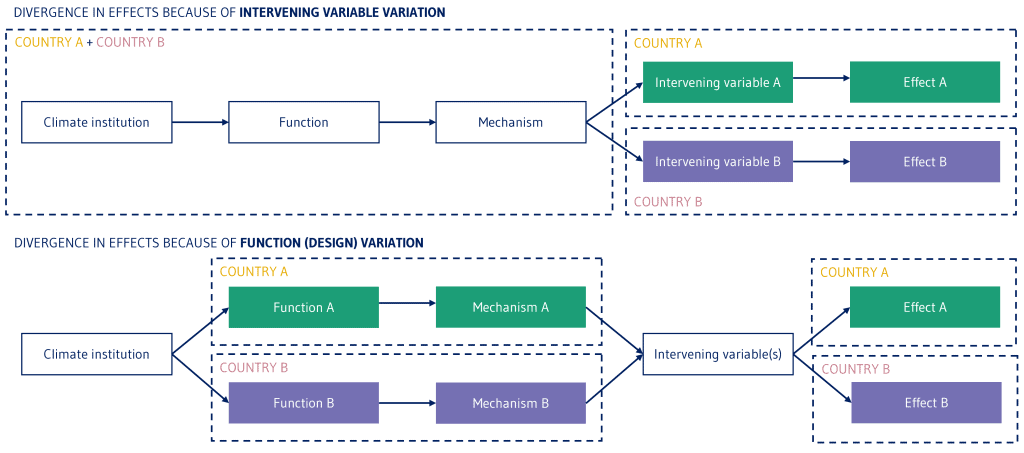

These stylised causal chains address three shortcomings of existing frameworks. First, the limited literature on the effects of climate institutions tends to conflate two distinct sources of variation: (i) variation in the functions or design of institutions (see section 4.3.1), and (ii) variation that arises from intervening variables (e.g. policy entrepreneurship). Institutions may impact policymaking in different ways across different contexts for two reasons: either because they have different functions, or because their effects are moderated21We follow the literature on causal inference in distinguishing between mediated and moderated . An effect is said to be mediated by some variable if this variable is the mechanism through which the effect engenders a certain outcome. An effect is said to be moderated when some intervening variable changes the marginal effect of an explanatory variable on the outcome of interest. Formally, this amounts to hypothesising the derivative of the marginal effect with respect to the intervening variable of interest (cross-partial derivative) to be statistically significant. by different sets of intervening variables, despite being designed similarly (see Figure 6). Conflating these two sources of variation together is problematic for comparative analyses given a key objective is to investigate how and why the same types of climate institutions affect policymaking differently across countries. Our framework therefore distinguishes between the functions and effects of institutions, with differences in functions capturing design variation. By holding the design of institutions conceptually constant, this distinction allows us to determine whether differences in effects are attributable to variation intervening variables, the design of institutions, or both.

Source: Own illustration.

Second, the climate institutions literature tends to treat mechanisms as a ‘black box’, with few studies analysing how an effect is engendered (see section 2.3.2). In contrast, our framework makes mechanisms explicit. This helps explain variation in how the same types of climate institutions achieve similar effects in different political contexts – which in turn is useful for generating hypotheses about this variation and suggesting improvements to countries’ climate governance landscapes. If an institution that is not present in, for example, Germany has a similar effect across the other three countries via (i) a consistent mechanism that is (ii) likely to operate in Germany, then we have some reason to believe the institution’s effect may be replicable in Germany. Conversely, a mechanism that is at odds with central planks of Germany’s political system or culture should give us pause as to the institution’s potential to generate this effect in Germany. If we found, for instance, that the integration-enhancing effect of the UK’s climate-focused inter-ministerial coordination mechanism22A body established to coordinate the process of developing and implementing climate policy among various relevant ministries or departments. relies on the Cabinet Office having substantial power over departments, we should we sceptical about a similarly designed institution promoting integration in Germany, where the Ressortprinzip23 Article 65 of the German Basic Law (“Grundgesetz”) safeguards ministries’ independence vis-à-vis the Bundeskanzleramt (Meinel 2019, 68).

Third, institutional frameworks often ignore agential factors, thus entrenching an unhelpful dichotomy between institutional and agential theories of climate policymaking. Agential factors include, for instance, the actions of bureaucrats, the media, politicians, academics, and other relevant political actors. Structural or institutional factors, by contrast, include electoral rules, the strength of political parties, and the nature of a country’s interest group system. Both types of factors may influence climate policymaking, especially the effects of climate institutions. By introducing the analytical category of ‘intervening variables’, we ensure our institutional framework can acknowledge the role of both.

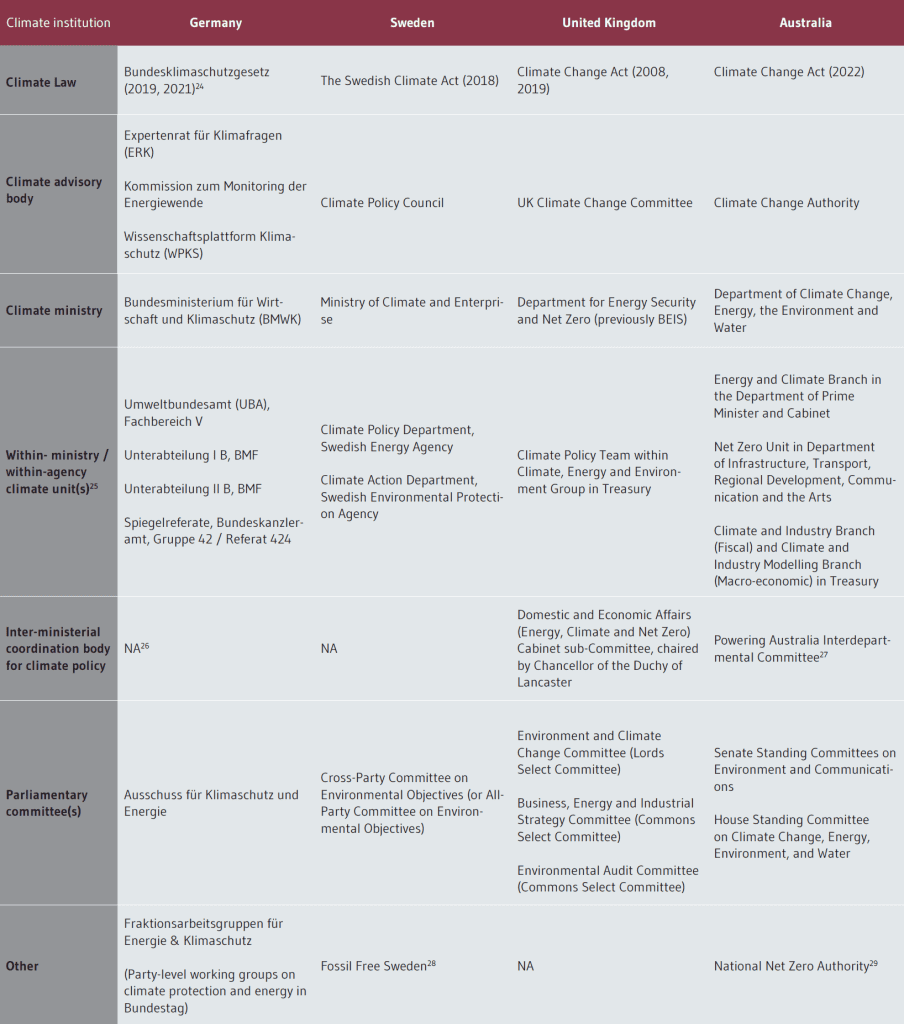

4. Results

This section summarises the results of our study, drawing on analysis of literature and interviews. We begin by identifying the institutions present in our sample which satisfy our criteria for ‘climate institutions’ (Table 5, below). Section 4.1 provides relevant context for our cases, including key macro-political institutional features which may act as intervening variables on effects. Section 4.2 presents our within-case analysis: including the most important institutions, key institutional effects, as well as institutional deficits and reform options highlighted within each country in our sample. Section 4.3 summarises our analysis across the four cases, examining the variation in functions and effects.

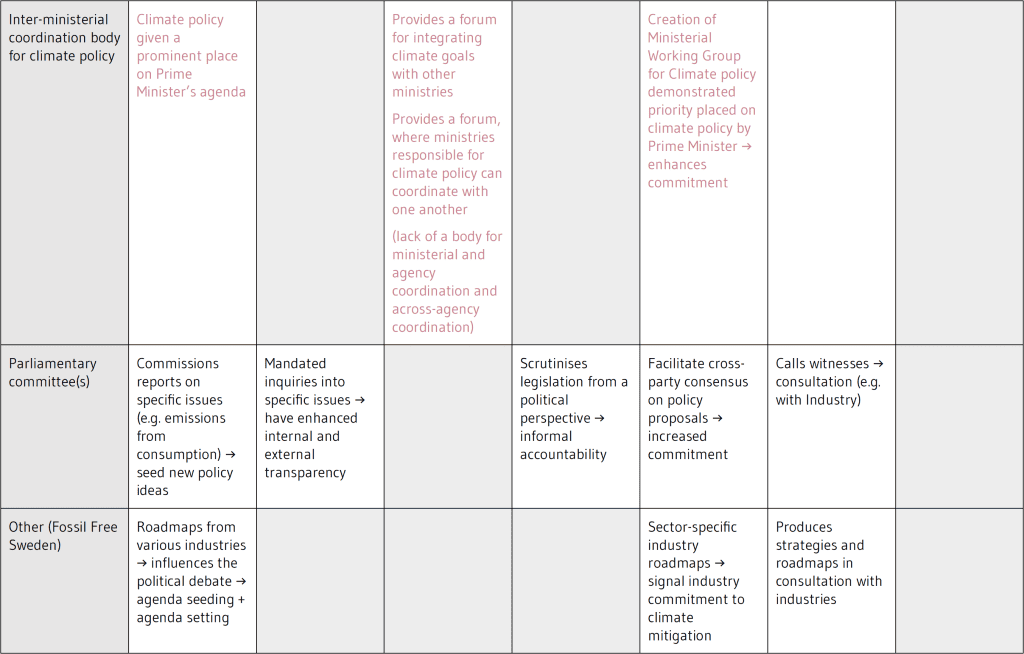

24Dates indicate the year in which a given piece of framework legislation initially entered into force and was, in some cases, subsequently amended. At the time of finalising this report (early August 2023), the traffic-light coalition’s amendment had not been adopted by parliament, which is why we have not added ‘2023’ to the German cell., 25It is likely that more of these units exist and are not included here, either because we did not identify them, or they were in the process of being created during the period of our analysis., 26The Klimakabinett is currently inactive (see also sections 4.1, 4.2.1, and 5)., 27This is a somewhat borderline case because the inter-ministerial committee is focused on a single, albeit central, climate policy., 28Fossil Free Sweden is an initiative by the Swedish government to develop roadmaps for the transition of various sectors of the economy. It does this through consultation between the government and business representatives., 29This authority was established after the substantive period of our analysis and so is not explored in detail below.

4.1 Context

This section offers a brief overview of the country contexts in which the climate institutions in our sample operate. Examining the different contexts helps to identify potential intervening variables that may influence the effects of climate institutions. Because our framework distinguishes between structural and agential intervening variables, this section highlights three sets of variables: (1) electoral rules and particularly how these support Green party success, (2) the structure of multi-level governance, and (3) features of the political context (e.g. actions of politicians (Shepsle 2017)) in each country, where relevant. The justification for (1) is that parliamentary representation of Green parties is – following Hughes and Urpelainen (2015) – taken to be a proxy for the institutionalisation of pro-climate opinion. This is a conservative proxy; almost all electoral systems lead to some degree of disproportionality between Green parties’ seat and vote shares, with vote shares usually being higher than seat shares. Examining the structure of (2) multi-level governance – notably the structure of the state (unitary vs. federal) and / or EU (non-)membership – is important because these distinct, albeit related, levels of governance affect not only the formulation of national climate policy, but also its delivery. Finally, (3) political features – such as polarisation surrounding climate policy – can shed light on factors that amplify or mute institutional effects. While we acknowledge that these are not the only relevant macro-institutional variables, we think they provide a good starting point for formulating hypotheses about the role different types of intervening variables play in the four countries in our sample.

Germany: Germany exhibits strong institutionalisation of pro-climate public opinion – its political system has facilitated the emergence and consolidation of a powerful green party for two reasons. First, the mixed-member PR (proportional representation) system enabled the Greens to develop into a potent parliamentary force at the national level (Harrison 2010).. Secondly, the Greens’ growing national importance has been bolstered by their strong performance in some states (Länder). Their state-level success – especially in the last two decades – has translated into participation in various state coalition governments, which has allowed the Greens to influence national climate policy through the Bundesrat, Germany’s Länder-centred upper chamber, even when they were in opposition nationally. Because of the relatively high number of veto points implied by federalism and bicameralism, policy change requires broad consensus (Saalfeld 2004), which is reinforced by Germany’s corporatist tradition.

The combination of Germany’s federal structure and EU membership means that climate policy requires vertical coordination between the central government, the state governments and the EU. As a result, the state governments are constrained by both national and EU climate policy. In the realm of climate policy, German federalism thus allows for less subnational experimentation or policy entrepreneurship than, for instance, Australia. Similarly, national climate policymaking is heavily influenced by EU climate policy, particularly with the adoption of the EU Green Deal. Horizontal coordination between ministries is strongly shaped by an idiosyncratic institutional feature, namely the constitutionally enshrined Ressortprinzip (article 65 of the Grundgesetz). By granting ministries a fair amount of autonomy vis-à-vis the Chancellery, the Ressortprinzip implies that successful policy delivery requires genuine coordination between the centre of government, the Chancellery, and other ministries (Grotz and Schroeder 2021, 272–73). Usually, horizontal coordination cannot be achieved by the Chancellery simply giving orders to other ministries. This is especially true for coalition governments and those ministries controlled by parties other than the Chancellor’s party.

United Kingdom: In the UK, two institutional factors are of particular significance for climate policy: its majoritarian electoral system and the system of devolved administrations embedded in an otherwise unitary state. The first-past-the-post electoral system – by incentivising strategic voting in favour of large parties (e.g. Cox 1997) – has made the emergence of a powerful green party extremely difficult, with the Green Party of England and Wales (GPEW) currently holding only one out30In early June 2023, Caroline Lucas, the only Green MP, announced her intention to step down as MP for Brighton Pavilion at the next General Election (Lucas 2023). of 650 seats in the House of Commons. The GPEW’s lack of parliamentary clout means a relatively small number of Members of Parliament (MPs) champion ambitious climate policy and those that do are not organised in a political party, raising the costs of coordination. This is reflected in the relatively low salience of climate policy in the party manifestos and parliamentary behaviour of the two major parties, which may, in part, be attributable to the low salience of climate policy – relative to, for instance, the general state of the economy – among the general public (Kenny 2022). In addition, the UK’s increase in devolution31 Devolution refers to the central government in England granting greater autonomy to (i) the other three countries that are part of the United Kingdom (Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland), and, (ii), to increasingly, sub-national regions within England, such as mayoral combined authorities (Henderson 2023). since the late 1990s has brought the importance of vertical coordination between the central government and devolved administrations into sharp relief, particularly as the Scottish government adopted more ambitious climate legislation in 2009 than the UK government had done a year earlier (Nash 2021).

With respect to political context: it is worth noting that, unlike in other majoritarian democracies, such as the USA and Australia, both major parties in the UK have recognised climate change as an urgent challenge – though the recent attacks, intensified in the wake of the Conservative’s surprise victory in the Uxbridge and South Ruislip by-election, on the government’s commitment to the Net Zero target by senior Tories demonstrate the fragility of this consensus (Rutter 2023; Cooper and Dawson 2023). Moreover, strong elite-level policy entrepreneurship has characterised UK climate policy. This is exemplified by the actions of (former) politicians, notably Lord Deben32Lord Deben retired in late June 2023, and, at the time of finalising this report (early August 2023), it is not clear who will take over as chair of the UK CCC, with interviews for potential successors expected to be finished by mid-August (UK Government 2023b). Piers Forster was appointed interim chair in late June (UK CCC 2023c). in his capacity as the former UK CCC chairman, academics, including Lord Stern, author of the Stern Review, and civil society organisations, such as Friends of the Earth, whose ’Big Ask Campaign’ played an important role in establishing the UK CCA (Lorenzoni and Benson 2014; Carter and Childs 2018).

Sweden: In contrast to the UK, Sweden employs an open-list PR electoral system, which results in a relatively large and ideologically diverse number of parties gaining parliamentary representation. This includes the Swedish green party, the Miljöpartiet, which currently holds 18 out of 349 seats in the Riksdag. While this suggests that pro-climate public opinion is fairly strongly institutionalised, PR also implies that typically only coalitions can form governments. Large-scale policy change is therefore premised on cross-party agreements. The need for broad compromise is, as in Germany, reinforced by Sweden’s corporatist tradition de facto requiring the government to consult industry groups, labour unions and other key stakeholders on major legislative proposals (Kronsell, Khan, and Hildingsson 2019; Gronow et al. 2019). Another important institutional characteristic is Sweden’s combination of small ministries and large bureaucratic agencies (Johansson 2020), meaning that much of detail of drafting policy proposals is left to career bureaucrats in agencies, rather than bureaucrats or politically appointed officials in ministries. This has implications for policy integration and coordination as well as technical capacity for strategic climate policy planning, as we discuss below. These domestic institutions notwithstanding, EU climate policy significantly shapes what domestic targets, policies, and institutions Swedish policymakers adopt. EU membership has been associated with policy convergence (Strunz et al. 2018), and may act as a commitment device, making Swedish climate policy reversals less likely.

Finally, a relevant piece of political context is that, at the 2022 general election, a Moderate-led minority government gained power, whose parliamentary survival depends on the support of the right-wing, Eurosceptic Sweden Democrats 33While the Sweden Democrats do not hold any cabinet posts, they ensure the government’s survival via a confidence-and-supply agreement. (Rothstein 2023; Aylott and Bolin 2023). The Sweden Democrats are opposed to ambitious climate policy: they seek to lower taxes on electricity, for instance, and to reduce Sweden’s fuel emissions reduction target (Hivert 2023). The influence of this party in the governing coalition has potential to stymie or even reverse stringent climate policy.

Australia: Like the UK, Australia has a majoritarian electoral system, which has also made it challenging for the Australian Greens to gain a strong foothold in parliament. This has impeded the institutionalisation of pro-climate public opinion for much of the last two decades. Following the 2022 election, however, pro-climate forces – notably the Green party and the so-called ’Teal’ independents – have become important power brokers since Anthony Albanese’s government only commands a majority in the House, but not the Senate, therefore requiring the support of these pro-climate forces to pass legislation. This is borne out by the negotiations that preceded the recently adopted Safeguard Mechanism Amendment Bill. The second significant piece of institutional context is Australia’s federal system, which has allowed for considerable sub-national action on climate change (Christoff and Eckersley 2021), even when anti-climate forces dominated nationally. Politically, the most striking feature is how polarising an issue climate change has been in Australia, particularly during the ’climate wars’ of the 2010s. The ’climate wars’ led to high policy instability, perhaps best illustrated by the Gillard administration’s introduction of the Carbon Pricing Mechanism in 2011 and its subsequent repeal by Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2014. This inability to credibly commit to ambitious climate policy, in large part, reflects the political influence of the fossil fuel industry, given Australia’s role as a major resource, especially coal, exporter, and has led to Australia being perceived as a climate laggard internationally (Zwar 2022).

4.2 Within-case analysis