Executive summary

Why should we analyse climate institutions?

Countries around the world have set increasingly ambitious targets to mitigate climate change. To deliver on these targets, policymakers have (i) implemented new policies, (ii) increased the ambition of existing policies, and (iii) created ‘climate institutions’. A substantial body of research is devoted to the first two phenomena. Yet we know little about climate institutions, despite their proliferation. This is a significant gap, which matters because climate institutions formalise the process of climate policymaking, steering its development, delivery, and potential improvement.

Existing research offers no systematic definition or framework for cross-country analysis of multiple climate institutions. Most studies focus on a single type of institution, such as climate laws or climate advisory bodies (Duwe and Evans 2020; Weaver, Lötjönen, and Ollikainen 2019; Evans and Duwe 2021) and their effect on a single outcome (e.g. transparency, commitment). Others adopt encompassing definitions covering multiple climate institutions (MacNeil 2021), which obscure important differentiation between formal and informal institutions, and test their correlation with policymaking outcomes, e.g. stringency (Guy, Shears, and Meckling 2023). As a result, we lack a nuanced understanding of the range of effects of climate institutions and the mechanisms by which these occur. This is necessary to shed light on the impact of climate institutions on climate policymaking and to inform proposals for designing and reforming these institutions

Approach

This report therefore seeks to answer three research questions. First, what are climate institutions and how can we characterise them across countries? Second, what effects do climate institutions have on climate policymaking? Third, in light of these findings, what insights can we draw for German climate governance and what options exist for institutional reform? We propose a definition of climate institutions and develop a conceptual framework for analysing and comparing their effects. We test the framework on a sample of four countries: Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Australia. We selected wealthy democracies which have developed climate institutions, but which vary in terms of their macro-political context. Germany and Sweden are corporatist, EU members with coordinated market economies; the UK and Australia are pluralist, non-EU members with liberal market economies. This diverse case selection approach recognises that macro-political institutional features can influence climate policy outcomes. By allowing us to identify common features of climate institutions across different contexts, we can also identify necessary conditions for an institution to classify as a climate institution and therefore develop a clear definition. Our case analysis draws on 22 interviews with climate policy experts (~5 per country) and desktop analysis.

Source: Own illustration.

What is a climate institution?

We define a climate institution as a formal, state institution established to steer the development and / or implementation of national climate mitigation policy from a multi-sectoral perspective. The types of institutions that meet these criteria are: (i) climate laws, (ii) climate advisory bodies, (iii) climate ministries, (iv) within-ministry / agency climate units, (v) inter-ministerial coordination bodies, (vi) parliamentary committees. We also include a country-specific ‘other’ category. Although this definition does not include all institutions which matter for climate policymaking, it allows us to differentiate effects of climate institutions from other (e.g. informal, non-government) climate-related institutions. Its narrow scope and formalistic focus also ensure a high degree of replicability, which helps to clearly identify these different types of institutions across the four countries in our sample and can inform future comparative work in this field.

An analytical framework to analyse climate institutions

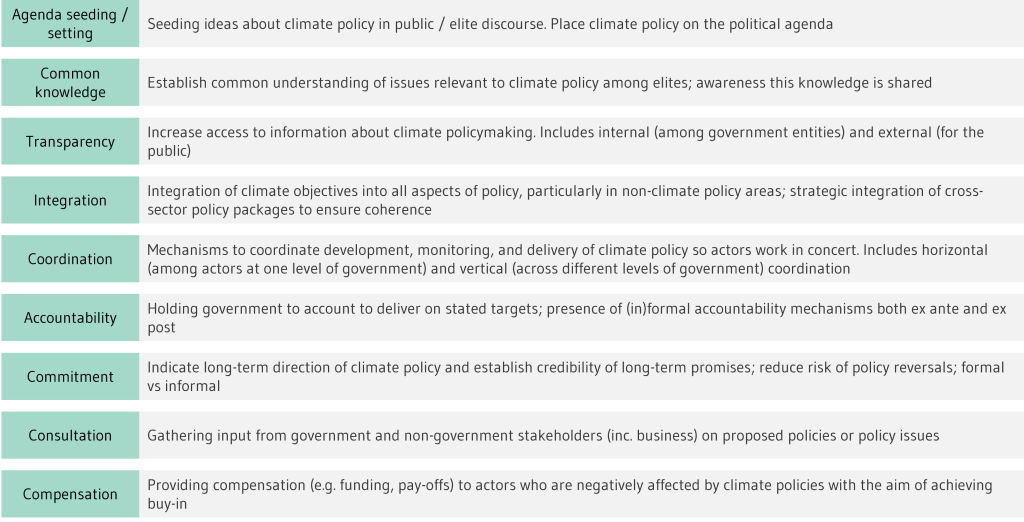

Drawing on a review of the literatures on policymaking, in general, and climate institutions, in particular, we devised a framework to analyse the effects of climate institutions. ‘Strategic challenges’ are its first plank. Climate change policymaking is characterised by a series of complex challenges. These include: the need to credibly commit to long-term targets, the need to compensate losers from climate policy, the need to coordinate implementation across all sectors of the economy, and to establish basic knowledge and transparency in climate policymaking. Following, inter alia, Averchenkova and Nachmany (2017) and MacNeil (2021), we conceive of institutions as a means to respond to these strategic challenges. A classic response to the challenge of commitment, for example, is to delegate policy decisions to independent institutions (Gilardi 2002). Figure 1 summarises the list of strategic challenges, derived from the literature on the role of institutions in climate policymaking and effects of climate institutions.

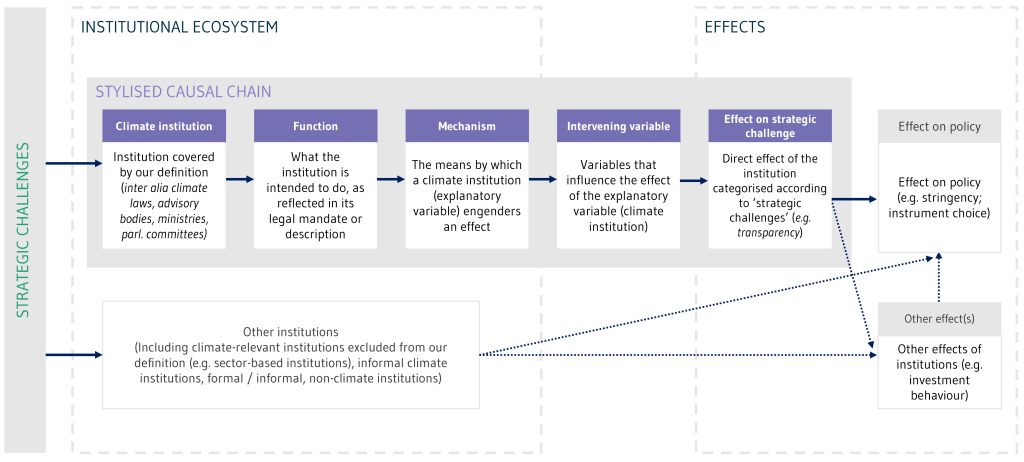

The second plank of our framework is the ‘stylised causal chain’ which illustrates how climate institutions engender effects on climate policymaking via addressing these strategic challenges. The chain (Figure 2) consists of the institution’s function, what it is intended to do, as specified in its mandate or the relevant piece of legislation, the mechanism by which (how) an effect is engendered, an intervening variable which influences the effect and the effect on the strategic challenge (e.g. achieving commitment). Figure 2 also indicates that effects on strategic challenges have knock-on effects on policy (though the broken line indicates that we do not explore this in our analysis), and that climate institutions and other institutions can have other effects.

Source: Own illustration.

Results

We present our results (i) within each country in our sample, (ii) comparing functions of institutions across cases, and (iii) comparing effects of institutions across cases.

Within-case analysis

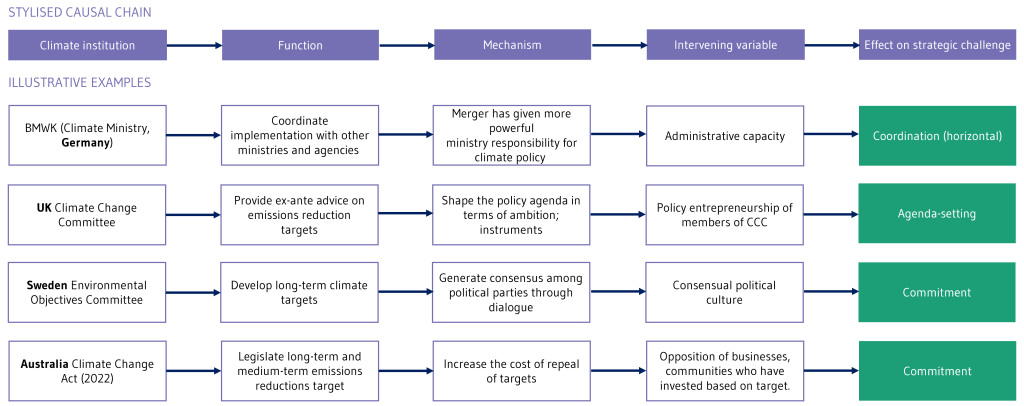

Contrary to the literature, which tends to focus on climate laws and climate advisory bodies, we discovered a rich landscape of climate institutions across our cases. The figure below (Figure 3) highlights four stylised chains from across our sample to illustrate our analytical approach.

Source: Own illustration.

Variation in functions

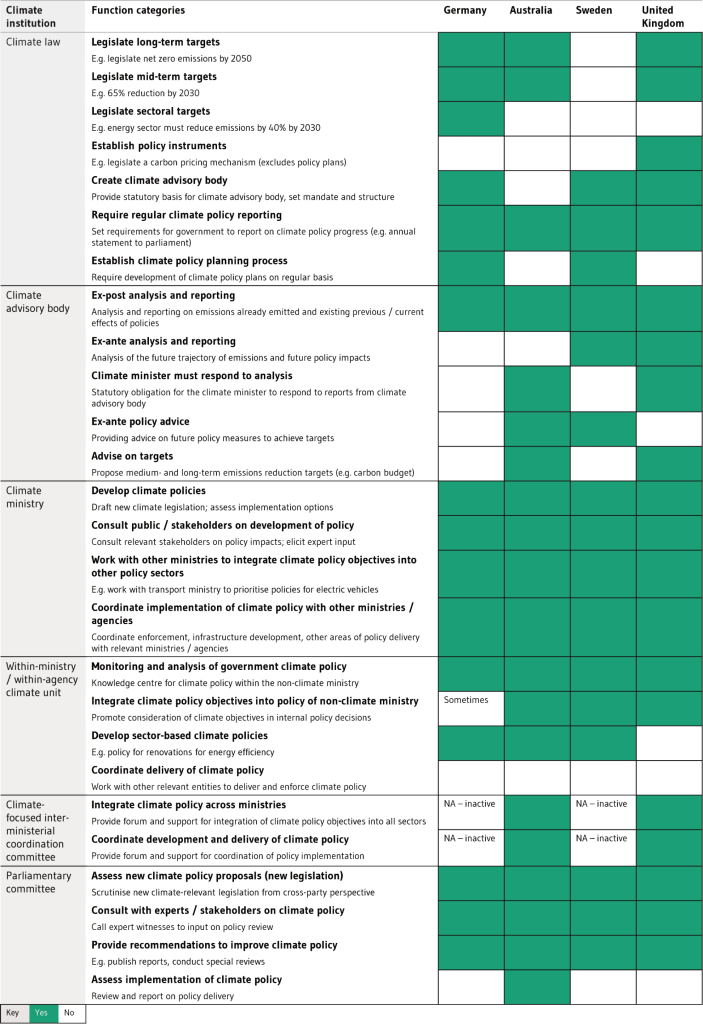

Variation in the design of institutions is greatest among climate laws and climate advisory bodies (see Table 1). Climate laws vary in whether they legislate targets, whether they require governments to adopt climate policy plans, and whether they legislate specific policy instruments. Climate advisory bodies all provide ex-post analysis, but vary in the extent to which they provide ex-ante analysis and ex-ante policy advice. Other institutions – like climate ministries and parliamentary committees – are more similar across cases.

An overarching insight is that several types of climate institutions serve the function of imposing a regular process for climate policymaking. Climate laws, for instance, impose a timeline upon which climate policy is created and delivered – for example through five-year carbon budgets in the UK, annual reports to parliament in Australia, and climate policy plans2Germany’s Climate Action Plan is pursuant to Article 15 of the European Governance Regulation (KSG 2019, secs 1, §2, 7.), which suggests “Member States should, where necessary, update those strategies every five years” (EU 2018, arts. 15, 1.). Under the draft amendment to the Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz, the German government will be obliged to produce a new climate policy programme within twelve months of the start of a new legislative term (BMWK 2023b, secs 3, §9, (1)). that should be published every four years (Sweden) or five (Germany) years. Climate advisory bodies, similarly, publish reports according to a regular, mostly annual, timeline, contributing to a legally specified rhythm of scrutiny. Other institutions also contribute to this policy process – e.g. climate units publish emissions data, climate ministries prepare policy plans. With the proliferation of climate institutions, we observe the consolidation of a ‘climate policy cycle’, itself comprised of multiple cycles of (usually annual) monitoring and (usually five-year) planning.

Variation in effects

Our comparative analysis of effects of climate institutions found that most climate institutions address (i) attention-related and (ii) epistemic, or knowledge-related, strategic challenges. All institutions in our sample have some kind of agenda-setting effect – including through developing the substance of climate policy, and / or facilitating the climate policy process described above, whereby climate policy is regularly returned to the political agenda. Many promote transparency – both within the government and for the public – and contribute to the establishment of common knowledge about climate policy impacts and policy solutions.

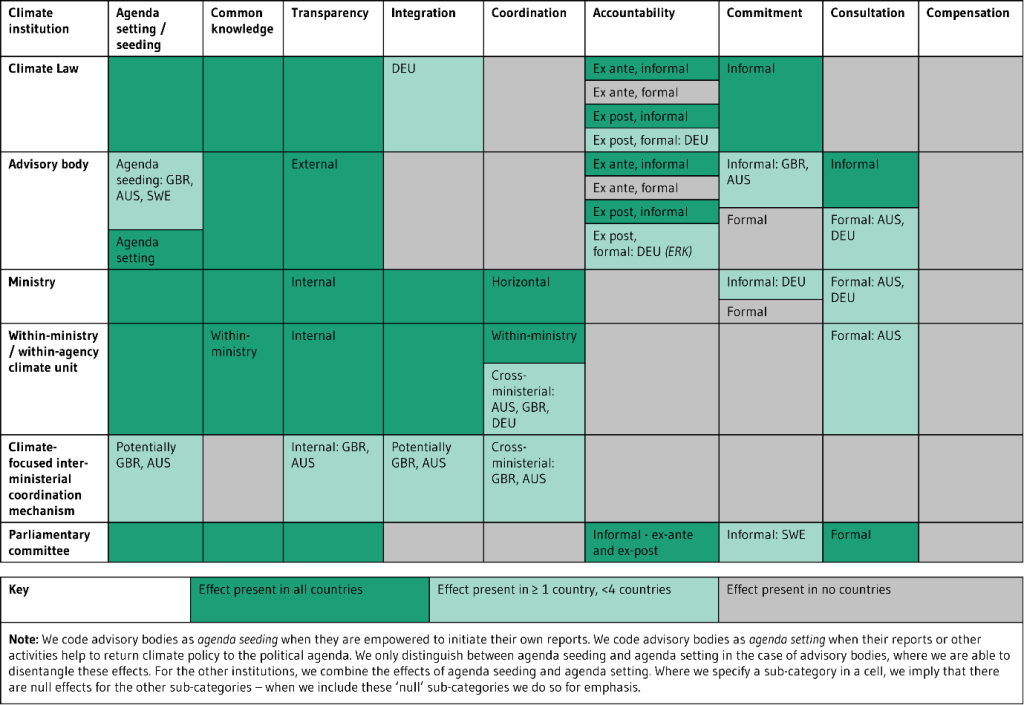

Table 2 summarises institutions and their effects across cases, with cells coloured according to number of countries in our sample, where we found the effect to be present.

There are few institutions, on the other hand, that facilitate integration and coordination. It is notable that a ‘climate cabinet’ – with potential to enhance integration – has been created and subsequently dismantled in two (Germany and Sweden) of our cases in the past. Save for the newly created National Net Zero Authority / Economy Agency3On 14 June 2023, the government announced that the agency “has been established as an interim step whilst a statutory Net Zero Authority is established. The Agency will also undertake work to design and establish the statutory Authority.” (PM&C 2023b) in Australia (not included in our analysis because of its novelty), no climate institutions exist to deliver compensation for actors who stand to lose from climate policy. Finally, climate laws are the primary devices through which governments create and bolster their commitment to long-term climate policy goals; and all institutions are limited in the degree to which they can hold governments accountable.

Insights for German climate institutions

In late March 2023, Germany proposed an amendment to the Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz (KSG), the Klimaschutznovelle (Koalitionsausschuss 2023), with potentially profound implications for German climate institutions. Our analytical framework and comparative analysis help us shed light on (i) how the Klimaschutznovelle may address deficits in the landscape of German climate institutions and (ii) deficits that will likely remain, even if the amendment is implemented as proposed. We discuss how the amendment might help Germany better grapple with five strategic challenges – integration, horizontal coordination, transparency, accountability, and agenda seeding / setting – and leverage our comparative analysis to identify options for institutional reform aimed at filling some of the key remaining gaps.

Integration and horizontal coordination

The Klimaschutznovelle has the potential to address integration-related deficits by adopting a whole-of-government, as opposed to a sector-specific, approach to devising Sofortprogramme (immediate action programmes): it abolishes Germany’s annual sector-specific reduction targets (Sektorziele) and explicitly mentions the option that ministries suggest cross-sectoral measures to correct overshoot. Yet, the amendment does not set out procedures for devising and evaluating cross-sectoral Sofortprogramme, nor does it contain suggestions for improving coordination between ministries. To help fill these gaps, we outline the following reform options:

- Option 1: Establish a procedure for crafting cross-sectoral Sofort- and Förderprogramme. One approach may be to specify an iterative, two-step process. First, the government could adopt new or adjust existing cross-sectoral policies. In a second step, it could consider sector-specific measures to close the gap between the emissions reductions required for it to meet its annual reduction target(s) and the likely emissions reductions delivered by the cross-sectoral measures. In this way, Sofort- and Förderprogramme (subsidy programmes) could enhance integration by encouraging cross-sectoral policy reforms.

- Option 2: Adopt additional criteria for evaluating cross-sectoral Sofort- and Förderprogramme. There is an opportunity to expand the range of criteria used to evaluate Sofort- and Förderprogramme beyond their potential for emissions reduction. Additional evaluative criteria could include fiscal costs, cost effectiveness, and the programmes’ distributive implications – as well as the trade-offs between these criteria across alternative policy pathways.

- Option 3: Establish intra- and inter-ministerial working groups to support coordination and integrated climate policymaking. These groups could provide a forum for dialogue between ministries, help to synthesise information from across government, and elicit expert input. In this way, intra- and inter-ministerial working groups would facilitate a coordinated approach to climate policymaking which aims to achieve coherence across climate and other policy objectives.

- Option 4: Reinstate the Klimakabinett. Several countries (including, in the past, Germany) have tried to address the challenge of horizontal coordination by creating ‘climate cabinets’ (Klimakabinett): a forum where ministries with portfolios relevant for climate policymaking can coordinate its development, monitoring, and delivery. There is an opportunity for Germany to reinstate its climate cabinet – though this requires political will and may be more challenging when ministries are controlled by different parties.

Transparency and accountability

Ex-ante accountability – the ability to hold the government to account to deliver on future emissions targets – is relatively weak under the original KSG, which grants the Expertenrat für Klimafragen (ERK) a narrow mandate to analyse policy measures. The modelling, commissioned by the German Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt, UBA), used to produce the Projektionsdaten (projected emissions) is also limited by a lack of transparency and narrow scope of the scenarios that are analysed. The Klimaschutznovelle potentially boosts informal, ex-ante accountability by granting the ERK the right (Initiativrecht) to initiate analyses of policy measures without an explicit request by either government or parliament. Yet, the overall effect on accountability is ambiguous because abolishing the legally binding Sektorziele (sector targets) also weakens ex-post, formal accountability. To increase transparency and overall accountability, we outline three reform options:

- Option 5: Improve ex-ante analysis via more transparent modelling by the UBA. Transparency could be improved by (i) increasing access to the technical approach adopted in the UBA’s modelling and (ii) increasing the scope of the scenarios considered to include measures currently not considered by the government.

- Option 6: Boost the ERK’s analytical capacity to enable it to effectively deploy its Initiativrecht. Providing ex-ante advice on policy measures requires detailed ex-ante analysis of policy instrument mixes and pathways. There is an opportunity to expand the ERK’s analytical capacity to help it deliver this advice, for instance through increased resources to contract research, by teaming up with other expert bodies, or by endowing the ERK with in-house modelling capacity.

Agenda seeding and setting

The amendment’s Initiativrecht does not only improve the ERK’s ability to hold the government to account ex-ante, but also enables it to follow the lead of other climate advisory bodies, notably the UK CCC, by playing a greater role in seeding ideas about climate policy and shape the climate policy agenda. We therefore suggest the following reform option:

- Option 7: Strengthen agenda setting and seeding via more active policy entrepreneurship by the ERK. The ERK could act as a ‘policy entrepreneur’ – by, for example engaging more actively with a range of stakeholders and the media. Greater policy entrepreneurship, however, comes with the risk that the ERK will be perceived as unduly activist, which would undermine its credibility. Shying away from a more entrepreneurial stance, similarly, comes with costs: it could prevent the ERK from realising the potential for greater agenda seeding and setting activity created by the Initiativrecht. Enhancing the ERK’s analytical capacity may help to resolve this tension by ensuring recommendations are supported by rigorous analysis.

Conclusion

This study seeks to (i) advance the still nascent academic literature on climate institutions and (ii) to improve the policy debate surrounding these institutions. By proposing a definition of climate institutions and a framework to analyse their effects, we address two gaps in the academic literature – namely, that we (i) lack conceptual tools for characterising climate institutions across countries and (ii) comparing their effects on climate policymaking. The results of our comparative analysis contribute to our understanding of climate change governance in each of these countries, while our analysis of the German case specifically contributes to the ongoing policy debate about the likely impact of the Klimaschutznovelle. By applying our analytical framework to identify reform options for German climate institutions, we further demonstrate how it can be used as a diagnostic tool to identify deficits and a structured approach to ‘learning’ from other countries based on comparative analysis.

Jacob Edenhofer is a graduate student at the University of Oxford and contributed to this report as member of the Ariadne project team at Hertie School.

This Ariadne report was prepared by the above-mentioned authors of the Ariadne consortium. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the entire Ariadne consortium or the funding agency. The content of the Ariadne publications is produced in the project independently of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

References

Averchenkova, A., & Nachmany, M. (2017). Institutional aspects of climate legislation. In A. Averchenkova, S. Fankhauser, & M. Nachmany (Eds.), Trends in Climate Change Legislation (pp. 108–122). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Referentenentwurf des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz: Entwurf eines Zweiten Gesetzes zur Änderung des Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetzes, (2023).

Duwe, M., & Evans, N. (2020). Climate Laws in Europe [Report]. Ecologic Institute, Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations. https://www.ecologic.eu/17233

REGULATION (EU) 2018/1999 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL, European Parliament and European Council (2018). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781782258674

Evans, N., & Duwe, M. (2021). Climate Governance Systems in Europe: The role of national advisory bodies [Report]. Ecologic Institute, Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations. https://www.ecologic.eu/18093

Gilardi, F. (2002). Policy credibility and delegation to independent regulatory agencies: A comparative empirical analysis. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(6), 873–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176022000046409

Guy, J., Shears, E., & Meckling, J. (2023). National models of climate governance among major emitters. Nature Climate Change, 13, 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01589-x

Koalitionsausschuss. (2023). Modernisierungspaket für Klimaschutz und Planungsbeschleunigung. https://www.wiwo.de/downloads/29065906/3/ergebnis-koalitionsausschuss-28-marz-2023_230328_200642.pdf

Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz (KSG), (2019). https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ksg/KSG.pdf

MacNeil, R. (2021). Swimming against the current: Australian climate institutions and the politics of polarisation. Environmental Politics, 30(sup1), 162–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1905394

PM&C. (2023, June 14). Appointment of Net Zero Economy Agency and Advisory Board | Prime Minister of Australia. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/appointment-net-zero-economy-agency-and-advisory-board

Weaver, S., Lötjönen, S., & Ollikainen, M. (2019). Overview of national climate change advisory councils. The Finnish Climate Change Panel Report. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/317713/Overview_of_national_CCCs.pdf?sequence=1