Table of Contents

- Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Ex-post evaluations processes in reflexive climate governance

- 3. Research design and procedure

- 4. Institutional configuration of governance of residential buildings in Germany

- 5. Ex-post evaluation: procedures, scope, data, and methods

- 6. Use of evaluations and effects on the policy process

- 7. Key reform options

- 8. Conclusions

Summary

Residential buildings directly contribute 11% to local greenhouse gas emissions and up to 40% of total emissions when accounting for energy use for electricity generation. In order to achieve the climate targets in line with the Federal Climate Protection Act, increased ambition level of climate policy instruments is required in this sector. In this research, we are interested in the governance of this sector and the role of evaluation: the government-mandated processes used to evaluate policy in terms of the actors, organisations and ministries involved in executing and coordinating these processes; and the metrics and methods as well as the scope and granularity of evaluations.

The report follows a mixed methods research design, utilising multiple sources of primary data for triangulation. We combine 14 expert interviews with content analysis of published reports to investigate the quality and scope of the current evaluation procedures in place. Building on institutional and evaluation literatures, the research offers an enhanced understanding of the content, scope and processes of ex-post evaluation of policy instruments.

We focus specifically on how evaluations effect subsequent policy design and calibration. In this way, we explore the potential impact of an evidence loop of policy instrument implementation on policymaking. Our analysis highlights methodological, scope and institutional limitations that effect the generation and use of evidence in the German domestic buildings sector. We identify procedural and policy options to help improve these processes with an aim to contributing to enabling more effective policymaking and implementation.

Ex-post evaluation quality has direct implications for ex-ante planning, including establishment of targets and strategies. Inaccuracies in evaluating the performance of policy instruments after their implementation can lead to inaccuracies in projecting the future greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction effects of planned policy mixes. This becomes particularly important considering the increased prominence of the “Projektionsbericht” in driving the reform of German climate policy mix, as envisioned in the draft Novelle of the Federal Climate Laws. Such inaccuracies could have significant implications for steering German climate policy. Reporting requirements under the KSG (Klimaschutzgesetz) are relatively recent, and the evaluation processes have not been sufficiently adapted to incorporate necessary criteria and include all policy programmes.

The scope of current evaluations is limited. Several key indicators need more attention and assessment methodologies to be developed in order to help make informed and strategic policy planning and design choices. The most notable omissions are distributional impacts, governance capacities, and dynamic cost effectiveness.

The GEG is not currently evaluated, nor is there an ex-post evaluation planned. Regulatory costs are not considered as direct costs to the government, and this area of policy has not received the same level of attention as fiscal spending. This overlooks the potential macroeconomic and welfare effects of introducing regulations, as well as the administrative costs required to effectively administer and credibly enforce them to ensure effectiveness.

The evaluation of regulations faces several key challenges related to data availability, enforcement, and accountability. The absence of data on energy use before the implementation of energy efficiency standards, makes it challenging to establish the baseline energy consumption and assess the impact of regulations. Furthermore, there is a lack of data on the effects of regulations after their implementation, mainly due to the absence of reporting requirements. Without comprehensive data on energy consumption patterns and performance indicators, accurately estimating the effectiveness of regulatory measures becomes a challenge.

A major challenge undermining the effectiveness of regulations is the lack of enforcement. Even if reforms are implemented to improve data provision and access, the effectiveness of these measures heavily relies on a robust inspectorate. Existing data protection laws create difficulties for the federal government in accessing regional data, which contribute to a lack of accountability. Consequently, the credibility and effectiveness of the inspectorate regime responsible for enforcing regulations are undermined.

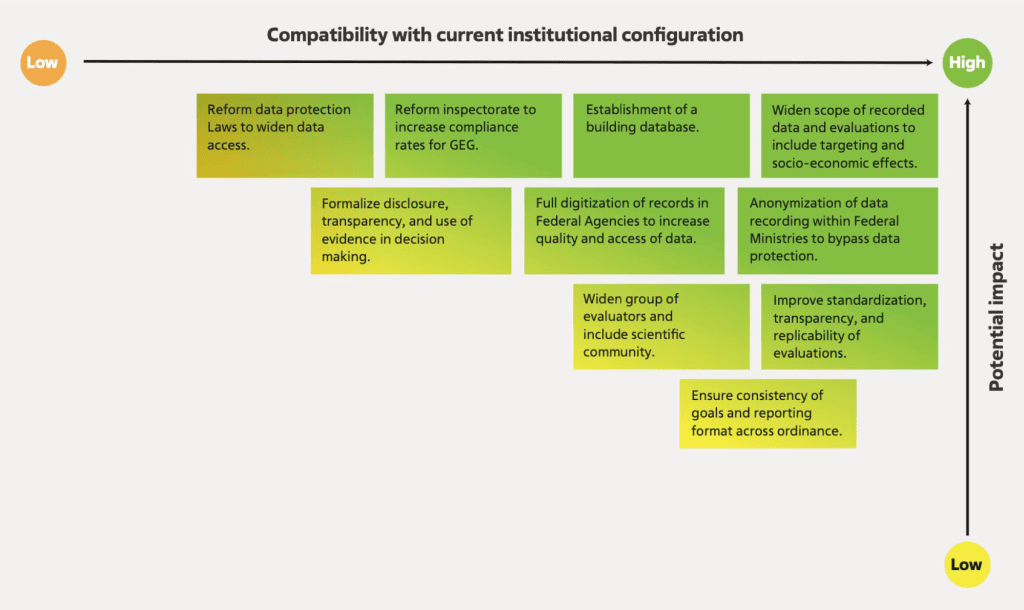

Key recommendations are:

- Development of a publicly accessible anonymised building stock database, including current building envelope efficiency standards, energy carrier and heat source efficiency rating.

- Expansion of local inspectorate training and expertise, and introduction of reporting requirements to federal government.

- Further standardisation of procedures, estimations, and assumptions across agencies and consultancies.

- Expand scope of evaluations and assessments to improve focus on socio-economic impacts, dynamic cost effectiveness, and more explicit treatment of governance and administration.

- Increase transparency of assumptions and parameters in modelling for top-down assessments and evaluations.

- Digitisation of data within funding agencies and increased accessibility, including public access.

- Enhance reporting and accountability for evaluations and assessments, beyond current scrutiny from Bundesrechnungshof of state budgetary spending and economic efficiency.

- Implement more accurate methods of measuring the GHG reduction effectiveness of instruments, especially energy efficiency measures.

1. Introduction

Reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the residential buildings sector is a major climate policy challenge. Progress in decarbonising the existing building stock has been slow in Europe and across the world. Germany has ambitious legally binding climate policy sector targets for GHG mitigation and has made significant progress in advancing evaluation procedures for domestic building policy in the past decade. Despite which, the decarbonisation of buildings has made less progress than other sectors. The effectiveness of previously implemented policy in Germany has been underwhelming, having missed the Climate Action Plan (KSG) sector targets twice previously (ERK, 2022).

Unprecedented climate policy ambition is needed for transformation and meeting GHG mitigation objectives. Key reforms include: the expansion of policy mixes to target multiple market and systemic challenges; the ratcheting-up of existing policy instrument stringencies; the removal of barriers to entry for emerging technologies; resolving distributional conflicts; minimising negative interactions between instruments; and addressing unintended outcomes. Critically, adaptive policy mix design needs to evolve to tackle changing conditions and uncertainties over time (Edmondson et al., 2023, 2022). To respond to these multi-faceted challenges requires reflexive governance processes: Reliable and timely production of evaluative data is needed to update and adapt policies dynamically, otherwise policymakers are constrained to drawing from a limited evidence-base, estimation, and may employ normative approaches of decision making (Fishburn, 1988).

Evaluation processes are needed to effectively manage energy transitions and update policy mixes. As numerous instruments are implemented to address these challenges, large numbers can accumulate through layering which adds governance challenges (Berneiser et al., 2021; Meyer et al., 2021). Accounting for instrument interactions is a key issue in the evaluation of policy mixes. At the most fundamental, resource constrained decision-makers need to know how to most effectively allocate funds to achieve most significant impacts on GHG abatement.

Improving capacities for reflexive governance can help reduce the likelihood of governance failures and can increase adaptability as expected changes in conditions arise. While there is an inherent and unavoidable amount of ex-ante uncertainty and complexity given the sheer scale and speed at which sector transformation has to occur in order to meet mitigation targets (Edmondson et al., 2022), reliable monitoring of policy effects can help improve the reliability of ex-ante approximations. This is particularly needed when scaling up previously implemented policy instruments to unprecedented stringency levels, or when trialling novel instruments or design features. The scope of the criteria included in the evaluations is also significant for the prospects for reform. If important effects are excluded from the evaluation of polices (e.g., distributional impacts) there is a lack of reliable evidence on which to base assessment and underlying assumptions about policy options. In these instances, more discursive or political narratives may play more significance, despite whether these are evidence-based. Consequently, what is included or excluded in evaluations can critically affect the framing of policy alternatives.

Institutional perspectives help identify structural dimensions of key dynamics in the policymaking process. Institutional perspectives relate to capabilities affecting the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of policies. The capacities of governmental departments, and their relationships with key actors involved in the evaluation of policies are particularly important (Meckling and Nahm, 2018). These procedural arrangements and coordination with governmental bodies, agencies, and preferred contracted consultancies, largely determine the quality, scope, and subsequent usefulness of policy evaluations (Schoenefeld and Jordan, 2017). Better understanding these linkages is central for unpacking the role of evidence in policy reconfiguration and policymaking outcomes. To date, there has been limited conceptual work explicitly focussing on how institutional arrangements may enable or constrain the production and the use of evidence in climate policy process (Hildén, 2011). By drawing from institutional literatures our paper contributes towards bridging the gap between public policy and public administration in the climate policy literature (Peters, 2012). We focus on: (i) the formal, structural and procedural arrangements and coordination of policy evaluation, (ii) the quality and scope of evaluations, and (iii) how relevant evaluations are for decision making and policy reform.

The building sector is complex due to heterogeneity of the building stock and split incentives. The heterogeneity of building stock (types of dwelling, retrofit and new buildings), and actors (renters, house owners, landlords, energy companies, installers, component manufacturers etc.) create multiple interrelated complexities in targeting decarbonisation (Moore and Doyon, 2023). Multiple policy interventions are used to target different abatement options (Edmondson et al., 2020). Further, behavioural characteristics such as rebound effects, mean the policies targeting buildings do not act uniformly and makes assumptions difficult and effects challenging to predict (Galvin and Sunikka-Blank, 2016; Sunikka-Blank and Galvin, 2012). From an energy transitions perspective, the building sector has historically been less well researched than other sectors such as electricity generation and transport (Köhler et al., 2019). Recent contributions have started to fill this gap (Edmondson et al., 2020; Moore and Doyon, 2023)

Sectoral institutional perspectives remain under researched, particularly in the building sector. Most of the existing contributions in the institutional literature focus on “climate policy” more broadly and explore variation of national climate institutions (Dubash et al., 2021; Finnegan, 2022; Guy et al., 2023). Consequently, little attention has been paid towards institutional configurations and capacities for climate policymaking processes at the sectoral level. Some contributions is the sustainability transitions literature with a sectoral focus have sought to better integrate the role of institutions, but these are often considered as contextual factors, rather than an explicit focus of the policy process (Brown et al., 2013; Gillard, 2016; Kern, 2011). In particular, there has been limited research directing attention to the institutional configurations which structure policy processes at the sectoral level. To address this gap, we map the institutions corresponding to the policy design and implementation processes in German residential buildings sector, paying particular attention to the role of ex-post policy evaluations in these processes.

Our research design combined mixed methods and multiple sources of primary data sources for triangulation. We combine institutional mapping, content analysis of published reports, and expert interviews, to analyse the development and influence of institutional arrangements on policy evaluation procedures and reforms. We present our assessment approach in Section 2, while our research design is detailed in Section 3. The institutional configuration of the governance of residential building policy is outlined in Section 4. Section 5 then combines content analysis and interviews to assess the current evaluation processes in terms of scope and quality. Section 6 focusses on the use and dissemination of evaluation processes in policymaking processes. Section 7 proposes key recommendations for reform, before Section 8 draws conclusions.

We discuss implications for policymaking in the German residential buildings sector and make policy recommendations for attaining climate policy ambitions moving towards 2030 and beyond. The report explores the broader question of how institutional configurations may facilitate or constrain the production of reliable ex-post policy evaluations and the use of evidence in dynamic and transformative policymaking processes. Germany has well-established and transparent institutional arrangements in this sector, making it an empirically rich case. In doing so, our research contributes to the salient discussion on the need for better evidence in the German building sector (Singhal et al., 2022), with a comprehensive examination of the institutional configuration which structures evaluation, and key recommendations to improve the quality and use of evidence.

2. Ex-post evaluations processes in reflexive climate governance

This section outlines our procedure for a systematic analysis of policy evaluations processes in the German residential sector. We introduce an analytical heuristic to study the role of evaluation in policy processes. The heuristic develops three frames which guide our line of enquiry throughout the research. First, a categorisation and utilisation of institutions for mapping the configuration of governance and evaluation. Second, policy design challenges and methodological considerations for assessing the scope and quality of current evaluation practices. Finally, key factors relating to the use of evaluations in the policymaking process.

Effective monitoring, evaluation and adjustment of policy is necessary for anticipatory policy mix design and reflexive governance. Successfully recalibrating policy design over time is needed to adapt to changing conditions and learning from previous implementation (Morrison, 2022). Similarly, revision of mitigation policies is needed given inherent uncertainties in carbon budgets (Michaelowa et al., 2018). The recent IPCC AR6 report indicates that the remaining carbon budget for the 1.5 target is only 50% of the previously anticipated target (IPCC 2023). The European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change’s recent report recommends EU wide 2040 climate targets (ESABCC, 2023), which may require further amendment to the German KSG targets. This highlights the need for adaptation, and potential acceleration of ambition and policy stringency.

Recalibration over time is assisted by reliable and timely production of evidence. Without evidence, decisions become inherently assumption-driven estimations based on limited data. While there are some inherent and unavoidable limits to data provision, especially in a rapidly changing environment, even estimates need to be based on what evidence is available. Evidence can improve several functions of reflexive governance: (i) monitoring and adjustment of instrument stringencies; (ii) monitoring compliance/evasion effects; and (iii) reducing negative interactions and layering of complex (and potentially conflicting) instrument mixes. Although there has been an increased recognition of the importance of policy evaluations in the broader academic literature (Fujiwara et al., 2019), there are only a few studies that systematically compile and evaluate the effects and outcomes of climate policy evaluations in practice. Some studies have conducted systematic reviews of ex-post climate policy evaluations, (Auld et al., 2014; Fujiwara et al., 2019; Haug et al., 2010; Huitema et al., 2011), but these studies primarily focus on the evaluation outcomes, whereas the quality of state-mandated evaluations is not considered to a large extent.

This report examines the institutional configuration, quality, and use of policy evaluations. We do so by focussing on three analytical frames related to evaluation processes: (i) the governance framework and institutional configuration of evaluation processes in the German residential building sector; (ii) the scope and quality of publicly accessible evaluations, (iii) the use of evaluations in the policy process.

2.1. Governance framework and institutional configuration of evaluation process

We categorise the institutional configuration of sectoral governance to consist of formal and structural elements. Formal institutions include major ordinance (laws and acts), policies and regulations (Kaufmann et al., 2018). Establishment of major ordinance often necessitates the establishment of programmes, and policy instruments to meet enshrined objectives. Structural institutions includes ministries/governmental departments tasked with design and implementation (Thelen, 1999) and supportive institutions which assist delivery and evaluation of policy instruments (Edmondson 2023). Structural institutions are configured towards the attainment of policy objectives enshrined in formal institutions (Steinmo and Thelen, 1992). This may involve recalibration of government capacities and responsibilities within the existing structure (Hacker et al., 2015), or formation of new arrangements which are dedicated toward the attainment of a particular objective (or function, e.g. monitoring commission). These institutional elements interact through procedural rules and practices (Skogstad, 2023), such as delegation and commissioning (Kuzemko, 2016; Tosun et al., 2019).

Evaluation processes play a key role within the institutional configuration of climate policymaking. Institutions both shape and are shaped by policymaking (Peters 2000). Policymaking is a constantly evolving, non-linear process (Edmondson et al. 2019), which plays out within the institutional configuration (Howlett and Ramesh, 2003). We consider three distinct phases of policymaking: (i) agenda setting; (ii) policy formulation and design; and (iii) policy implementation. National climate institutions have recently been demonstrated to affect phases of the policy process (Guy et al., 2023), yet the ‘climate institutions’ considered lack a clear definition in terms of being structural, formal, or procedural. Evaluation, monitoring, revision, and the input of evidence in decision making plays a key role in each of phases. Yet, the explicit role of evaluation within formal and structural institutional arrangements remains unexplored. We focus on this gap in the current literature, engaging substantively with the policy design and implementation phases, and the role which evaluations can play in shaping outcomes.

Agenda setting concerns how climate policy is understood as a policy problem by the state. This phase is largely dominated by political actors, and interests of competing political parties and stakeholders play out in decision making processes (Howlett, 1998). These processes commonly have a lower representation of bureaucrats, technical experts, or sectoral specialists, which can politicise the process of updating programmes at planned revision steps (Lockwood et al., 2017). Actors may influence these processes by increasing the visibility and salience of issues and framing of interests through public discourse or media (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981). We do not engage in these dynamics for the purpose of this report. We deem it sufficient to focus on the role that assessment and reporting can have on influencing this stage of the policy process, without engaging with causal links between evaluation outcomes and agenda effects.

Policy formulation combines political actors, bureaucrats, public bodies, and stakeholders. A policy subsystem is defined by a substantive issue and geographic scope, and is composed of a set of stakeholders including officials from all levels of government, representatives from multiple interest groups, and scientists/researchers (Howlett et al., 1996; Sabatier and Weible, 2014). The policy subsystem in the context of the residential sector in Germany is a configuration of stakeholders that coalesce around the objective of decarbonizing buildings. It encompasses officials from various levels of government, representatives from interest groups, and scientists/researchers (Mukherjee et al., 2021). While ministries play a significant role in overseeing key ordinances, departmental representation is not limited to specific mandates, as other policy objectives compete for support and resources (Öberg et al., 2015). Sector-specific policy programmes are typically designed and calibrated under the responsibility of ministries, but input from advisory committees, research offices, consultancies, and think tanks also influences the calibration and updating of instruments and programmes over time (von Lüpke et al., 2022). Reliable information is crucial for effective recalibration and updating of policy instruments and programmes, necessitating comprehensive evaluations that cover a broad range of indicators to inform design and recalibration choices.

The implementation phase plays a crucial role in determining the rate and direction of socio-technical change resulting from policy formulation and design. The policy design and institutional literature often overlooks the importance of implementation beyond the effective design of policy elements. In practice, policies often fail to achieve their intended effects due to institutional factors that influence (or limit) the impact on the target group (Patashnik, 2009). While implementation has recently been considered in relation to variation of national climate institutions (Guy et al., 2023), it corresponds only to a broad conceptualisation of “state capacities”. More specifically, administration and enforcement are critical capacities, which shape policy outcomes and effects (Edmondson 2023). These are typically carried out by delegated actors such as federal agencies, public bodies, devolved administrations, or local authorities (Cairney et al., 2016; Hendriks and Tops, 2003). Delegation is sometimes necessary for effective implementation, particularly when policies require local administration (Jordan et al., 2018). Ideally, delegated actors should be coordinated or supervised by centralized federal departments to enhance accountability, enforcement, and reduce evasion. Accordingly, evaluating the governance capacities for effective policy implementation is essential. The institutions responsible for policy evaluation should be efficient, effective, and well-coordinated. Therefore, the evaluation of instruments and programmes should explicitly consider the governance capacities for implementing policies effectively.

Evaluations may be susceptible to selection bias in their scope of measured indicators and their methodologies. Since evaluations can reveal significant issues with policy and its delivery, there is a risk of biased or selective evaluations (Bovens et al., 2008; Mastenbroek et al., 2016; Schoenefeld and Jordan, 2017). For example, governmental bodies with specific policy agendas may be less likely to challenge established policy goals during evaluations (Huitema et al., 2011). This may limit the generation of evidence which would otherwise motivate reform. Yet, independent evaluations may be constrained by limited data access (i.e., data protection laws), and even when published may have less influence in the policy process than more officially conducted or commissioned evaluations (Hildén, 2011).

2.2. The scope and quality of evaluations

Having outlined the institutional configuration of evaluation processes, we now outline factors related to the scope of indicators that should be considered in more comprehensive evaluations, and factors affecting their quality.

Scope

The scope of policy evaluation should extend to a wider set of evaluation criteria to enable sufficient data for effective design. To effectively govern the process of transition, policymakers need to have sufficient evidence to draw on (Edmondson et al., 2023). Planning processes are commonly reliant on estimations, limited data, modelling exercises and assumptions which fail to capture the complexity of real-world socio-economic conditions. When evaluating implemented policies, considered effects should extend beyond the energy savings and the cost of the programme. Multiple other issues important for political feasibility and welfare outcomes arise including distributional inequalities. Evaluation should consider the impacts of policy implementation on different income groups, and how fiscal subsidies are distributed across society (Zachmann et al., 2018). To improve these assessment and planning processes, a wide range of empirical data should be collected from existing policy implementation, which extends to potential barriers to implementation, political acceptance, and governance challenges. We build on evaluation criteria developed by Edmondson et al. (2022) as a framework for the scope of policy evaluations for the residential buildings sector (Table 1).

| Challenge | Components | Analytical elements for residential building sector |

|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Energy Use | – Energy before implementation – Energy use after implementation. Rebound effects. |

| GHG abatement | – Carbon intensity of energy carrier (emission factor). – Change over time (composition of electricity/energy mix). | |

| Interaction effects | – Positive interactions – synergies between instruments. – Negative interactions – conflicts which reduce energy savings. – Necessary interactions – conditions/interventions needed for other measures to achieve assumed effects (i.e. minimum efficiency standards for operation of heat pump). | |

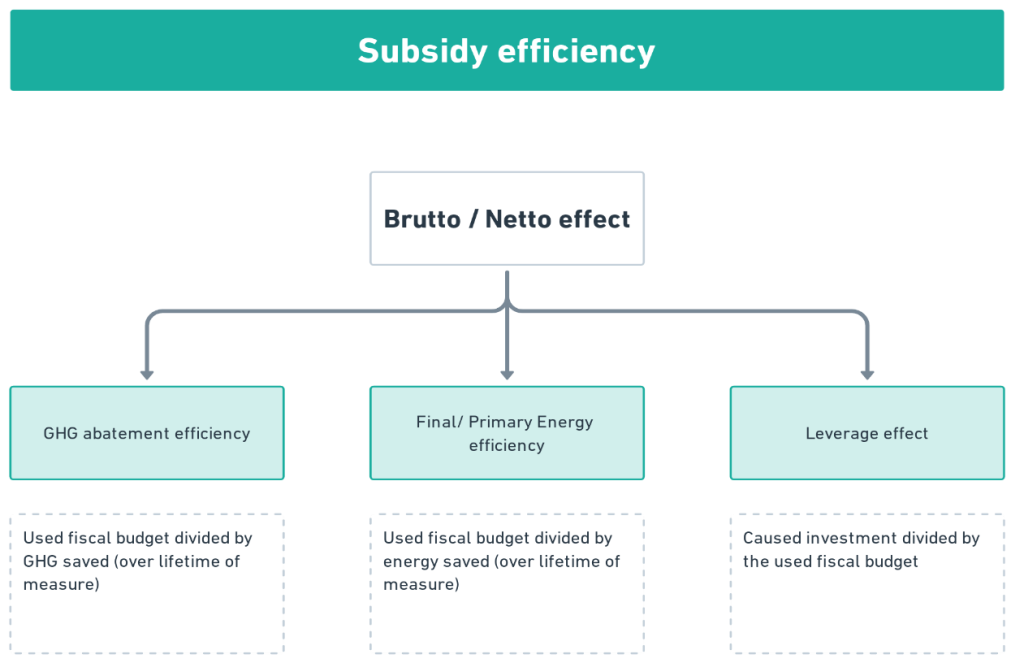

| Cost Effectiveness | Dynamic cost effectiveness | – Market failures, including: consumer myopia, learning by doing spillovers, R&D spillovers, network externalities. – Systemic failures: coordination, strategic and supply chain failures. – Investment effects. – Cost effectiveness over time under changing conditions (i.e., composition of energy mix). – Macro-economic effects over time. – Additionality of the programme/instrument. |

| Static efficiency | – Marginal abatement costs. | |

| Fiscal burden | Costs/revenues to state | – Fiscal costs/revenues generated from policy/programme. |

| Distribution | Population | – Distribution of costs and benefits among population. – Targeting of subsidies. – Direct distributional effects (subsidy). – Indirect distributional effects (energy use). – Market price of energy. – Cost allocation to landlord/tenant. |

| Firms | – Distribution of costs among firms and impacts on national competitiveness. – Creation of jobs. | |

| Acceptance | Population | – Acceptance among population groups. |

| Firms | – Acceptance among industry interest groups/stakeholders. | |

| Political | – Support by governing political parties. – Coherence between federal government and devolved authorities. | |

| Governance | Administrative/ information requirements | – Monitoring and enforcement capacities. – Compliance rates. – Information and data provision. |

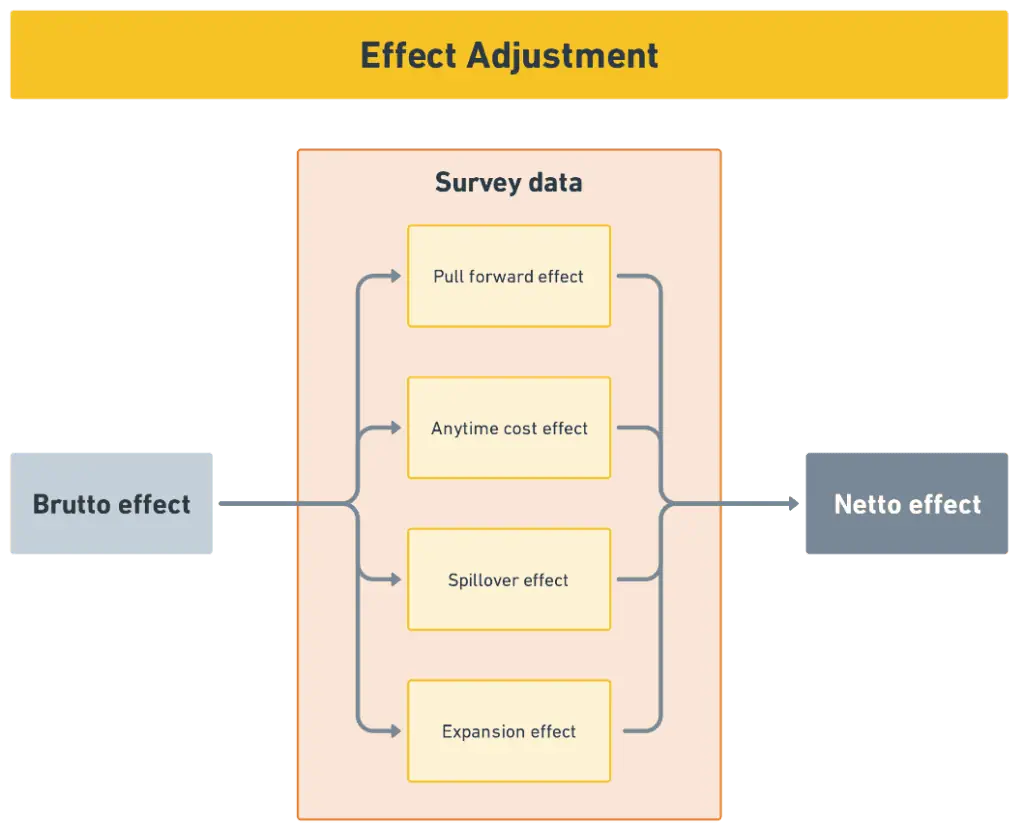

Effectiveness is the most fundamental consideration for policy evaluation. At its most basic, policy evaluation is needed to assess the effectiveness in attainment of goals, in terms of energy savings and GHG abatement. How effectiveness is measured can be in terms of absolute metrics (such as the total energy saved, or GHG abatement), or in terms of proxy indicators such as the number of heating systems installed as a percentage of the total stock (Edmondson et al., 2023). The first category gives a more quantifiable value for input into impact models and assessment tools, but the calculation methodology to estimate these values becomes very important. For example, inaccuracies in the baseline energy use prior to the implementation of policy and measures to target GHG reduction can overestimate their impact, i.e. ‘pre-bound’ effect (Galvin and Sunikka-Blank, 2016; Sunikka-Blank and Galvin, 2012).

The cost effectiveness mitigateion is another significant consideration. Policies incur costs, either to fiscal budgets, or socialised and distributed throughout the economy. Cost effectiveness of policy options has been a main focus of historical German evaluations (Rosenow and Galvin, 2013). How these costs are calculated will significantly affect the viability of some policy options over others. While regulatory policies have no direct costs, they incur administrative costs (Baek and Park, 2012). Compliance also incurs short-term costs for firms and/or households, but sunk costs pay back over a longer period through reduction of heating costs (Qian et al., 2016). This creates split incentives between landlords and tenants, based on who bears the cost of compliance and who benefits (Melvin, 2018). Economic policies do not have direct costs on fiscal budgets but incur costs across population groups (Wang et al., 2016). Accordingly, to effectively evaluate a broad range of policy instrument types and meaningfully compare options, requires evaluation of a wider range of factors including: macroeconomic costs, distributional effects, and governance requirements (administrative/enforcement costs).

Evaluations should explicitly consider dynamic effects and societal impacts. To consider cost effectiveness from a more dynamic perspective requires a consideration of innovation, market and systemic failures, and policy instrument interactions over time. For example, the GHG abatement of very high standards of renovation is greatest for a household which still uses a gas-based energy carrier for space heating. However, as the energy carrier decarbonises, the GHG abatement from the renovation decreases. Since the highest rates of efficiency renovation already have steep marginal abatement costs (Galvin, 2023), these would become even higher considered dynamically over time. Similarly, market and systemic failures (Weber and Rohracher, 2012) should be considered to assess potential issues and bottlenecks which would hinder delivery or cost effectiveness (Edmondson et al., 2023). These effects need to be anticipated and mitigated (to the extent possible) through policy design. However, these should also form a key aspect of policy evaluations. The wider impacts of policy design have societal implications. For example, the targeting of policy subsidies may lead to regressive distribution, where funding is only made available to homeowners. Equally, incentivising landlords to improve the efficiency and energy carrier of housing, whilst not incurring adverse costs on tenants is an important issue (George et al., 2023).

The governance requirements and capabilities of the state to implement and administer climate policy are important considerations to ensure the effectiveness. Assessment should not focus only on the estimated impacts of the instrument itself and draw broad assumptions about implementation and administration. Instead, evaluations should extend to the capacities of the state to effectively implement and enforce policy. Some policies are critically dependant on the monitoring and enforcement to ensure that they achieve the anticipated levels of energy savings and GHG abatement. In particular, regulatory measures need to be credibly enforced, otherwise non-compliance and evasion are likely (Garmston and Pan, 2013; Hovi et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2022). Effective implementation requires sufficient capacities (technical skills and training, budget allocation, retention/turnover of staff), coordination across ministries and agencies (horizontal), and between different levels of government (vertical). Evaluations should seek to assess these aspects of policy performance and governance capacities explicitly (Edmondson 2023).

Quality

The quality of evaluations is highly dependent on the availably and quality of input data. Unreliable input data necessitates the use of estimation and approximation for the effects of instruments and programmes. This can result in over-estimates of the effectiveness of the current policy mix (van den Bergh et al., 2021). In some instances, a poorly performing policy mix may not be recognised as such. Accordingly, ineffective instrument designs and programmes may persist and undergo small incremental changes (Jacobs and Weaver, 2015). More accurate evidence which highlights undesirable effects or cost (in)effectiveness of the existing programme may motive more radical reforms. Accordingly, evaluation processes should identify the quality and reliability of the input data. This should be indicated as uncertainty in evaluation outputs. More importantly, identified issues in data availabilities should be addressed to enable more reliable and robust outputs. These should be identified explicitly and motive institutional reforms to enable more informed policymaking.

Evaluation procedures have been demonstrated to vary in quality, which limits the reliability of evidence generated. To ensure evidence-based decision making, evaluations must have sufficient methodological quality and legitimate analyses. Research has shown that there usually is a disparity between evaluation theory and practical implementation (Huitema et al., 2011). These differences can be attributed to several factors, which include the transparency, replicability and reliability of the methodologies employed and the data used.

Interaction effects need to be considered. Policy evaluation needs to account for the interaction effects of individual energy saving measures and of the instruments which make up programmes (Rosenow et al., 2017). Governance involves evaluating and calibrating large numbers of interacting instruments. At minimum, the consideration of interactions should extend to instruments which may have negative interactions and reduce the anticipated energy saving/GHG reductions, both in the short term (static) and over time (dynamically). A more sophisticated integration of interactions would also elucidate: (i) positive interactions, in which two instruments have synergistic effects greater than the sum of their parts; and (ii) necessary interactions, in which a complimentary instrument is required to create the conditions necessary for the primary instrument to achieve its goals.

Standardisation is needed to ensure reliability and comparability of evaluation outputs. Without standardisation of processes evaluators often use differing methodologies, and apply divergent assumptions or approximations (Huitema et al., 2011). This makes the dissemination of results more difficult, and comparisons across evaluations more difficult. Good evaluation governance should seek to establish comprehensive and standardised procedures of practice, with formal disclose requirements (Magro and Wilson, 2017; Schoenefeld and Jordan, 2017).

The production of evaluations should prioritize the generation of outputs that are reliable, robust, transparent, and publicly accessible. This is essential for enhancing the transparency and accountability of policy design options. To achieve this, it is important that the outputs of evaluations demonstrate consistency across various publications. Standardized assessment methodologies and reporting requirements should be established to ensure uniformity and comparability. The data used in evaluations should be transparent, allowing for a clear understanding of the sources and methodologies employed. Furthermore, any gaps in the available data should be acknowledged and clearly identified. It is crucial that evaluation outputs are made publicly available to facilitate external scrutiny and validation. This enables a broader range of experts and civil society to participate in the evaluation process, contributing to its credibility and robustness.

2.3. The use of evaluations in the policy process

Effective evaluations of both policy instruments and state capacities are needed to motivate and inform reform. Over time policy implementation can produce feedback effects, which may motivate reform. These include perceptions of if a policy is working (cognitive effects), which contribute to perceptions of if incremental or more radical reforms to existing programmes (agenda effects) are needed (Edmondson et al. 2019). These cognitions are highly dependent on the reliability and evidence produced from evaluation processes, including how the evidence is presented and disseminated. Another element of feedback is perceptions of how well administrations tasked with policy design and implementation are performing (Oberlander and Weaver 2015). Administrative feedback can motive the expansion of state capacities (Pierson 1993) or other forms of institutional reforms (Edmondson et al. 2019). Without supportive evidence, feedback is purely discursive and normative, lacking objective information on which to base assessments (Schmidt, 2008). In these situations, ineffective policy mix elements may remain in place without scrutiny. Additionally, more effective reforms and policy options may not be considered, since current policy evaluations indicate the current programmes to be performing sufficiently (Weaver 2010). Accordingly, funding and human capital may be allocated to supporting programmes which do not deliver at the scale and speed needed to meet GHG abatement targets.

Ex-ante assessments and informed strategic planning of policy options necessitate the availability of reliable evidence. Ex-ante planning exercises rely on assumptions and the existing evidence base derived from previously implemented policies. Given that meeting climate targets is a long-term endeavour, it involves establishing policy trajectories and making adjustments over time. Consequently, the accuracy of these planning exercises is heavily reliant on the quality and accessibility of ex-post evaluations. Ex-post evaluations play a crucial role in assessing the outcomes and impacts of past policies, thus providing valuable insights for future planning. The availability of comprehensive and reliable ex-post evaluations is essential for enhancing the effectiveness and precision of strategic planning processes in achieving climate targets.

The integration of evidence into decision making processes could be more formally established. Decision makers could be obliged to draw on more reliable evidence in order to justify their choices, ensuring that decisions are based on a solid foundation of information and enhancing their quality and effectiveness. This formal integration of evidence can contribute to depoliticising decision-making processes by relying on evidence-based approaches, making decisions less influenced by subjective biases and personal interests. Furthermore, the inclusion of evidence allows for increased engagement from civil society, enabling them to scrutinize decision makers and hold them accountable. This participatory approach promotes transparency and democratic governance. Formal integration of evidence is crucial for holding policymakers accountable, as clear criteria for decision making and the requirement to use reliable evidence can be established. This makes it possible to evaluate and assess the outcomes and impacts of policies, ensuring that policymakers are answerable for their actions. In particular, under the Climate Protection Act, production of better evidence is needed both for review and scrutiny of progress and for the projection report (section 4.1.2.). Robust and comprehensive evidence is essential in identifying areas where policies may be falling short in achieving their objectives. This enables targeted interventions and course corrections to be made.

Motivation for conducting evaluations and their commissioning influences their eventual utility. The use of evaluative evidence also has path dependent elements, since ministries commission these, if not conducted in-house (i.e. UBA, dena). Therefore, the specification of these reports can largely determine the scope, quality, and use. The motivation behind commissioning the reports is important. If these evaluations primarily serve to justify how a ministry has allocated funding to support programmes, then methodological bias might exist that shows cost effectiveness more favourably. Accordingly, additionality and other factors which might impair cost effectiveness may be excluded from the evaluations, or considered in a more symbolic manner.

3. Research design and procedure

The research design of this report followed three main procedural steps. The first step included literature review and exploratory and descriptive desk-based research to characterise the governance framework in the German residential building sector. The second step included content analysis of methodological guidelines, and published publicly available ex-post evaluation reports. Finally, step 3 involved conducting expert interviews which helped corroborate findings and identify less codified procedural aspects of conducting evaluations and their impact.

Step 1: Governance framework for residential buildings in Germany and institutional configuration

Preliminary analysis followed a top-down approach to identify the governance framework in the Germany residential building sector. The first step followed a top-down approach to identify the governance framework for energy policy in the German residential building sector, focussing on the role of ex-post evaluation. It began by examining relevant EU directives and Germany’s current obligations. The analysis linked the governance framework to the institutional configuration, mapping interactions across ordinances and reporting requirements. The objective was to categorise laws, strategies, and programmes, identify evaluation procedures and changes over time, and observe key themes and trends. Additionally, the institutional configuration of ministries, government bodies, agencies, and consultancies involved in programme implementation and evaluation was mapped, focusing on formal evaluative inputs and publicly available reports.

Step 2: Content analysis of evaluation guidelines and publicly accessible ex-post evaluations published after 2020

Content analysis was employed to evaluate the scope and quality of existing state-mandated evaluation processes. The coding process encompassed three main aspects: the scope of evaluation metrics utilized; the methodologies employed to assess the included metrics; and data quality, transparency and replicability. The coding approach incorporated both deductive and inductive elements for each category.

Regarding the scope, an extended set of indicators outlined in Table 1 (Section 2.2) was used as a normative set of evaluation criteria for “good practice”. Reports were coded according to indicators to determine which were accounted for, and if so, how they were defined and applied. For the measured indicators, the coding process included identifying the metrics used to measure the variable and the methodologies employed for their calculation. These metrics and methodologies were then coded in terms of their transparency, replicability, and quality.

We first coded the methodological guidelines and then assessed how these were used in practice in published evaluations. The procedure began with first coding the methodological guidelines, and then using these as a benchmark for what should be included in publicly accessible published evaluations. Published evaluation documents were then coded to identify disparities between recommended practices and actual implementation. This comparison sheds light on the differences between ideal practices and application. It also allows us to assess the extent to which procedures are standardized across ministries and consultancies.

We focus on formal reports published by ministries and contracted consultants as part of the formal evaluation procedures, after the publication of the methodological guidelines. We limit the scope to these formal reports published after 2020, since prior to that date the guidelines were less transparent and standardised. The publication of the guidelines was a response to this phenomenon, and thus detailed extrapolation of evaluations prior to their publication was not considered productive. Instead, we focus on the evaluation procedures introduced through the guidelines and evidence of their use in practice by focussing on the evaluations published after their circulation.

To enhance the traceability of our research design, we concentrate on formal and publicly accessible reports. This ensures a higher level of transparency in our analysis. The impact of un-commissioned policy evaluations and external reports is less traceable. Ministries are not obliged to respond to or acknowledge these publications, making it speculative to evaluate their use or impact. Furthermore, there are ongoing evaluations that are less formalized and not subject to reporting requirements, creating challenges in accessing data for independent research, including our own.

To identify relevant documents, we employed a systematic web-based approach aimed at amassing a comprehensive collection of materials. First, we searched official government portals, including ministries and agencies, to gather all available policy evaluations. This ensured that we captured a wide range of relevant documents directly from authoritative sources. Second, by expanding our research beyond government portals, we explored websites of consultancies, institutes, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Next, to further enhance the scope of our search, we utilised general search engines, thereby enabling us to explore a broader range of resources and gather additional relevant documents (Table 2). Finally, we carefully reviewed the additional collected documents for any potential references to other ex-post evaluations, ensuring a thorough examination of the available material.

| Institution type | Frequency | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Federal Government/ ministry | 5 | Bundesregierung, Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimschutz (BMWK), Bundesministerium für Wohnen, Stadtentwicklung und Bauwesen (BMWSB) |

| Federal agency | 6 | Bundesamt für Wirtschaft und Ausfurhkontrolle (BAFA), Umweltbundesamt (UBA), Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (BBR) |

| Consultancy | 9 | Prognos, Guidehouse, PwC |

| NGO/ Institute | 10 | Fraunhofer, Öko-Institut e.V., Dena |

| Other | 4 | Expertenrat für Klimafragen, KfW |

During the screening process, we identified a wide range of documents. The selection of screened documents (Annex I) extended to: (a) strategies specifically related to energy efficiency; (b) ex-ante evaluations, which provide insights into the assessment of policies before their implementation; and (c) national monitoring reports that dedicated sections to energy efficiency in the building sector, thereby offering valuable information and analysis.

We selected documents which directly related to the generation of ex-post evaluations. From the screened documents, we narrowed down our selection to those directly related to the generation of ex-post evaluations (Table 3). These included:

- The methodological guidelines for ex-post evaluations and ex-ante assessments. These resource helped us understand how ex-post evaluations are conducted and feed into ex-ante assessments following standardised procedures.

- Ex-post evaluations that were conducted subsequent to the publication of the methodological guidelines. These evaluations offered insights into the outcomes and impacts of implemented policies.

- Sections within the national monitoring reports that specifically focused on residential buildings’ energy efficiency. These sections provided valuable data and analysis in the context of our research.

Content analysis employed framework coding as the main data evaluation procedure. Content analysis involves the coding of selected pieces of text according to specific coding categories (Krippendorff, 2004). Deductively, coding started with a list of a priori policy mix design challenges defined by Edmondson et al. (2023), which relate to key assessment metrics which need to be targeted to ensure success of climate policy (Table 1). We followed (Mayring, 2000) and first created codebooks in MAXQDA with a standardised definition, indication, exemplar recommendation and coding rules for each category. This improved inter-coder reliability and the replicability of our method.

Additional codes were added inductively through application of the codebook. New sub-codes were added inductively while coding the methodological guidelines to capture how the broad categories were applied in practice (where appropriate). This incremental process combined deductive and inductive elements. Procedurally, an inductive code book was created which included metrics, methodologies, relating to the use of the assessment criteria in the evaluation documents. Reports were double coded to improve reliability and replicability. Throughout, codes were iteratively reviewed, merged, or aggregated to avoid duplication, as per Krippendorff (2004).

| Type | Title | Publication Year | Authors | Client |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex-post evaluation | Evaluation und Perspektiven des Marktanreizprogramms zur Förderung von Maßnahmen zur Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien im Wärmemarkt im Förder-zeitraum 2019 bis 2020 | n.d. | ifeu, Fraunhofer, Fichtner GmbH | BMWK |

| Ex-post evaluation | Abschlussbericht zur Evaluation der Richtlinie über die Förderung der Heizungsoptimierung durch hocheffiziente Pumpen und hydraulischen Abgleich | 2022 | Arepo, Wuppertal Institut | BfEE |

| Formative Ex-post evaluation | Evaluation des Förderprogramms KfW 433 | 2022 | Prognos | BMWK |

| Formative Ex-post evaluation | Evaluation der Förderprogramme EBS WG im Förderzeitraum 2018 | 2022 | Prognos, FIW München | BMWK |

| Formative Ex-post evaluation | Förderwirkungen BEG EM 2021 | 2023 | Prognos, ifeu, FIW München, iTG | BMWK |

| Formative Ex-post evaluation | Förderwirkungen BEG WG 2021 | 2023 | Prognos, ifeu, FIW München, iTG | BMWK |

| Guidelines | Methodikpapier zur ex-ante Abschätzung der Energie- und THG-Minderungswirkung von energie- und klimaschutzpolitischen Maßnahmen | 2022 | Prognos, Fraunhofer ISI, Öko-Institut e.V. | BMWK |

| Guidelines | Methodikleitfaden für Evaluationen von Energie-effizienzmaßnahmen des BMWi (Projekt Nr. 63/15 – Aufstockung) | 2020 | Fraunhofer ISI, Prognos, ifeu, Stiftung Umweltenergierecht, | BMWK |

| National monitoring | Klimaschutz in Zahlen | 2022 | BMWK | n.a. |

| National monitoring | Klimaschutzbericht 2022 | 2022 | BMWK | n.a. |

| National monitoring | Zweijahresgutachten 2022 Gutachten zu bisherigen Entwicklungen der Treibhausgasemissionen, Trends der Jahresemissionsmengen und Wirksamkeit von Maßnahmen | 2022 | Expertenrat für Klimafragen | n.a. |

| National monitoring | The Energy of the Future 8th Monitoring Report on the Energy Transition – Reporting Years 2018 and 2019 | 2021 | BMWK | n.a. |

| National monitoring | Energieeffizienz in Zahlen | 2021 | BMWK | n.a. |

| Other | Begleitung von BMWK-Maßnahmen zur Umsetzung einer Wärmepumpen-Offensive | 2023 | Dena, Guidehouse, iTG, Öko-Institut, Prognos, EY, pwc, bbh, FIW München, ifeu, heimrich + hannot | BMWK |

| Strategy | National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency | 2014 | BMWK | n.a. |

Step 3: Interviews

The final stage involved conducting expert interviews. A part of our research motivation lies in examining the impact and utilisation of evaluations in policymaking processes, as well as the broader application of evidence in decision-making. It is worth noting that these processes often lack formalisation and are commonly not codified, making them inaccessible through content analysis. Hence, we rely on interviews as a means to thoroughly investigate these themes. The interviews aim to qualitatively explore the influence of evaluative processes on decision-making, as well as their connections to ex-ante assessment and forecasting. While decision-making is a crucial element of dynamic policymaking, we acknowledge that systematically dissecting these typically opaque processes was beyond the scope of our analysis. Furthermore, the interviews serve to complement the findings derived from content analysis and descriptive mapping of data.

We interviewed a range of different actor groups to represent different viewpoints. The sample of interviewees chosen for our study comprised various stakeholders, including ministries, agencies, public bodies, consultancies, experts, think tanks, and academia. In addition to scoping interviews, 12 interviews were conducted, following a semi-structured format (Annex II) with a duration of approximately 60 minutes each (Table 4). Among the interviewees, we engaged with key representatives from major consultancies (Prognos, Fraunhofer ISI, Öko Institut e.V., Guidehouse), as well as civil servants from the BMWK and BMWSB. However, it is important to note that one significant omission was the absence of federal funding agencies (KfW and BAFA) in our interviews. Despite multiple attempts to secure their participation, our requests were ultimately declined. We acknowledge this omission as a limitation in our research design since an important actor group was underrepresented. Nevertheless, we were able to address the coordination aspect with these funding agencies through discussions with other interview participants, thus partially mitigating the gap created by their absence.

| Interview | Actor group | Role/position | Organisation/Affiliation | Length (mins) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scoping interview | 45 | ||

| 2 | Scoping interview | 50 | ||

| 3 | Policymaker | Bureaucrat | Federal Ministries | 60 |

| 4 | Policymaker | Bureaucrat | 45 | |

| 5 | Policymaker | Bureaucrat | Federal Agency | 57 |

| 6 | Consultancy | Evaluator | Evaluation Consortium | 58 |

| 7 | Consultancy | Evaluator | 56 | |

| 8 | Consultancy | Evaluator | 115 | |

| 9 | Consultancy | Evaluator | 57 | |

| 10 | Consultancy | Evaluator | 59 | |

| 11 | Consultancy | Evaluator | Independent evaluator | 58 |

| 12 | Consultancy | Programme lead | Think tank | 65 |

| 13 | Expert | Academic | Monitoring Commission | 55 |

| 14 | Expert | Academic | University | 71 |

Interviews were transcribed, stored and coded using MAXQDA. Interviews followed a similar procedural logic in coding practice while also following a more inductive approach to creating a codebook. The purpose of the interviews was to explore views on procedural aspects of the evaluation process, including potential gaps, issues, or challenges in the production of evaluations, and their dissemination and use in policymaking. Accordingly, the codebook extended to institutional arrangements, including organisational structures, procedural logics, and constraining rules. Codes were iteratively reviewed, merged or aggregated (Krippendorff 2004).

Limitations

Access to interview participants reduced pluralism of groups represented in our interview sample. Our study encountered limitations due to restricted access to interview participants. Notably, we were unable to include representatives from BAFA and KfW, both crucial Federal agencies responsible for administering financial support programmes in the BEG. Despite reaching out to individuals from these organisations, our invitations to participate were declined. While this absence is a gap in our sample, we include multiple participants from other actor groups who directly interact with these agencies. By triangulating information from various sources, along with our interview findings, we believe that our research remains valid, even without the representation of BAFA and KfW.

Relatively limited availability of publicly accessible published evaluations. We examined the availability of publicly accessible published evaluations, focusing on reports published after the release of the methodological guidelines in 2020. The guidelines were developed to address the lack of standardisation across consultancies. Therefore, our analysis did not involve a detailed assessment of reports prior to 2020. Instead, we concentrated on: (i) the content of the guidelines to identify areas that still required standardisation, and (ii) determining the extent to which the guidelines were being followed in practice. For the second question, we analysed the content of published evaluations from 2020 onwards. However, our sample size was relatively small (n=14) due to a lower number of reports published during this period.

Generalizability of a single case study. Although this analysis is based on a single case study, the findings have implications beyond the specific context and can contribute to institutional learning and comparisons within other jurisdictions. The identified themes align with the broader literature on policy evaluation and monitoring, adding to the existing knowledge base. These themes include the limited enforcement of energy efficiency regulations, which is a commonly reported challenge that undermines the credibility and effectiveness of energy standards. The study also highlights the need for improved vertical coordination between different levels of government and emphasises the importance of robust methodological and analytical approaches to accurately monitor policy progress and assess the impact on greenhouse gas emissions. These themes provide valuable insights for on the generation and utilisation of evidence in climate policy processes. Further attention is needed to enhance the quality of measurements for effective policy design and calibration, as well as to enhance decision-making transparency and accountability.

4. Institutional configuration of governance of residential buildings in Germany

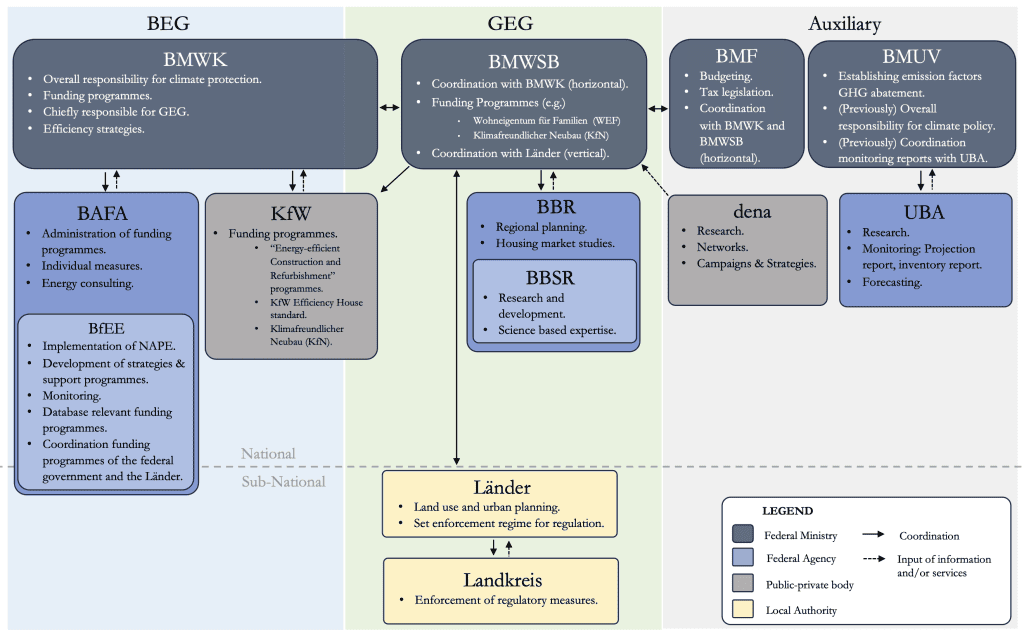

We map the configuration of formal ordinance for the residential building sector in Section 4.1., paying attention to reporting requirements. In Section 4.2. we map the structural configuration for two main programmes for delivery in this sector the BEG and the GEG. Section 4.3. then examines the relationship between the state and the consultancies commissioned to conduct evaluations in this sector.

4.1. Ordinance and reporting requirements

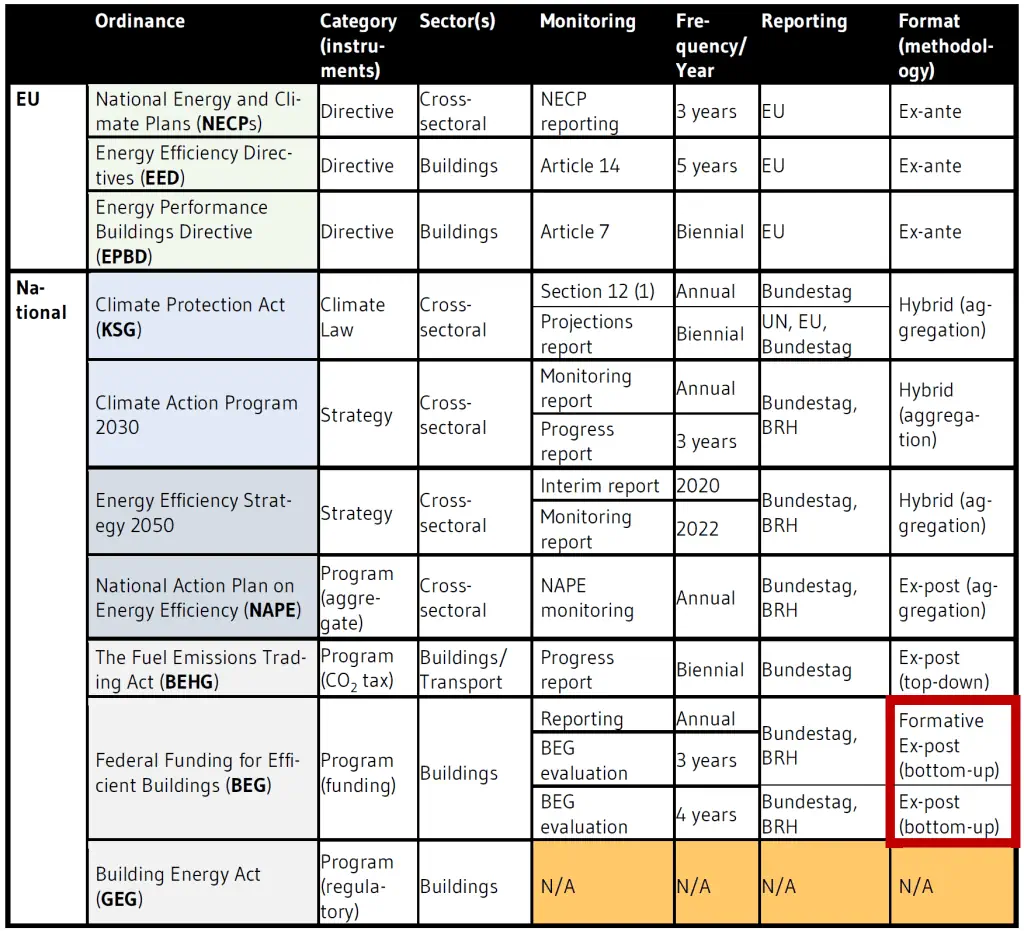

The ordinance and reporting arrangements for residential buildings in Germany spans multiple interacting levels of governance. The EU sets regulatory frameworks and has reporting requirements for member states (section 4.1). Germany has a climate law which establishes building sector GHG targets and is delivered through policy programmes under the mandate of Federal Ministries (Section 4.2.1.). Under the Climate Action Programme 2030, funding programmes are administered through Federal Agencies (4.2.1.), while regulatory are delivered and enforced at the regional level (section 4.2.3.). More information of on the content of respective ordinance is included Annex III.

4.1.1. EU directives and reporting

The EU Sets the overall framework for member states through Directives. The Energy Performance Buildings Directive (EPBD), the Energy Efficiency Directives EU/2018/2002 and 2012/27/EU (EED) establish many command-and-control polices for the energy performance of the building stock. The Renewable Energy Directive EU/2018/2001 (REDII) provides a framework for the expansion of renewable energy in the heating and cooling market at European level. Among other things, Article 14(1) EED obliges Member States to produce a report on heating and cooling efficiency every five years.

EPBD Article 7 (existing buildings) requires member states to explain where they deviate from EPB standards. Although the new EPBD does not force the Member States to apply the set of EPB standards, the obligation to describe the national calculation methodology following the national annexes of the overarching standards will push the Member States to explain where and why they deviate from these standards. This reporting is intended to drive implementation across member states “[it] will lead to an increased recognition and promotion of the set of EPB standards across the Member States and will have a positive impact on the implementation of the Directive.”

National energy and climate plans (NECP) reporting requirements draw primarily from national ex-ante assessments. The national energy and climate plans (NECPs) were introduced by the Regulation on the governance of the energy union and climate action (EU)2018/1999. The last reporting was included in the NECP in June 2020, and the next NECP will be due in June 2023.

Reporting requirements will be further consolidated under the EU Governance Directive. In the future, the European Union (EU) will consolidate the reporting obligations at the European level through the EU Governance Regulation (Directive 2018/1999), which was adopted at the end of 2018. This consolidation encompasses various obligations, such as the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs), the EU Energy Efficiency Directive (EED; Directive 2012/27/EU and revised 2018/844), the EU guidelines for evaluating state aid, and the European standards for CO2 monitoring and reporting.

EU reporting influences national policy implementation but does not carry penalties for non-compliance. EU reporting requirements are influential for policymaking and decision making and have to a large extent shaped the reporting procedures. They do not, however, carry penalties for non-compliance, and thus result in less accountability for the national Government than if clear penalties were established, or if commitments were legally binding.

4.1.2. Cross-sectoral ordinance

Climate Protection Act (KSG)

The KSG includes a legally binding sector target: GHG emissions in the building sector must be reduced by 68% by 2030 compared to 1990, with linearly declining annual targets throughout the 2020s. The revised Federal Climate Protection Act (KSG) establishes the commitment of the Federal Government to decrease greenhouse gas emissions by 65% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels and achieve greenhouse gas neutrality by 2045. The KSG also sets specific targets for different sectors. Regarding buildings, the aim is to reach 67 million t CO2eq. in 2030, which translates to a 68% reduction from the 1990 levels.

The climate goals are reviewed through continuous monitoring. Every two years, the German Council of Experts on Climate Change presents a report of the goals achieved, as well as measures and trends. The first Biennial report was prepared in 2022 (ERK 2022a). The report is subject to reporting requirements in the Bundestag, the EU and the UN. National reporting requirements carry more weight than the EU level, which are non-binding. If instruments cannot be proved effective, they must be reformulated or replaced. The council also prepares assessment on other aspects of climate mitigation. The council audited the Sofortprogramm’s effects on the buildings and transport sectors (ERK 2022b). More recently, the Review Report of the Germany Greenhouse Gas Emissions for the Year 2022 was published 17.03.2022 (ERK 2023).

The German government sees the projection report (Projektionsbericht), as a central monitoring mechanism for its climate protection policy. The impact assessment is mandated by the KSG [Section 9 (2) KSG], and is reported to the Bundestag and the Bundesrechnungshof (BRH) (BRH 2022: 38). In November 2021, the Federal Government adopted the Projection Report 2021 for the year 2020. For the first time, this report contains a forecast (ex-ante assessment) of the expected mitigation effect of the current climate protection measures (BRH 2022: 39). The next report (Projektionsbericht 2023) is still currently being developed.

Review by the Bundesrechnungshof (BRH) indicates the Climate Protection Report falls short of its monitoring objectives. BRH claim the report lacks important information such as the GHG reductions that the federal government expects from the individual climate protection measures or has achieved with them so far (BRH 2022: 37). According to the BRH, the previous climate protection reports did not contain any information on the effects achieved by the current climate protection measures, but claim the corresponding data was available to the Federal Government.

Current projections indicate that the existing climate protection measures are insufficient to meet these ambitious legal targets. Consequently, Germany is projected to face a reduction gap of 195 million t CO2eq in 2030, which accounts for 27% of the total emissions in 2020. In the buildings sector, emissions are estimated to only decrease by approximately 57%, a shortfall of 24 million t CO2eq (Umweltbundesamt 2022).

National Strategies/Programmes

The Climate Action Programme is the national cross-sectoral climate protection strategy. First introduced in 2014, there have been two subsequent strategies released in 2021 and 2022. The strategy covers all sectors, including multiple policy instrument types including support programmes, tax relief and regulatory measures.

The annual monitoring report is the core of the monitoring process for the energy transition. Every three years, instead of the monitoring report, the more detailed progress report on the energy transition is presented. On 3 December 2014, the Federal Government published such a progress report for the first time. With this report, the Federal Government simultaneously fulfilled its reporting obligations under Section 63 (1) of the Energy Industry Act (EnWG), Section 98 of the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG), and Section 24 of the Core Energy Market Data Register Ordinance (MaStRV), as well as under the National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency (NAPE) and the Energy Efficiency Strategy for Buildings (ESG). This reporting process condenses a large amount of available energy statistical information. Measures that have already been implemented are included in the analysis, as is the question in which areas efforts will be required in the future.

A commission of independent energy experts oversees the monitoring process. Based on scientific evidence, the members of the commission subsequently give their opinions on the Federal Government’s monitoring and progress reports. The report is prepared within the framework of two research projects supervised by the Federal Centre for Energy Efficiency (BfEE) at the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) and the Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

National strategies have auditing requirements. National spending strategies are subject to reporting and assessment from the Bundesrechnungshof (BRH), the supreme federal authority for audit matters in the Federal Republic of Germany. For all instruments measures which are relevant for public financing at the national level, BRH oversee auditing the success of these programmes, including how funding is spent and what is the efficiency of the subsidy programmes. They require figures for all financing relevant programmes every year, which is collected through commissioning ex-post evaluations [Interview 7, 8]. This has been conducted since the climate Action Programme 2020, which also included the National Action Plan energy efficiency in 2014, when these processes were established [Interview 7, 8].

Issues in monitoring were identified by BRH in previous assessment periods. The BRH’s assessment of the 2020 programme, identified significant problems in monitoring, as the GHG savings effects of the individual measures are not specified, and a large part of the measures do not directly contribute to a reduction. The BMUV justified its position by arguing that the projection report (every 2 years) did not consider recent developments such as the Immediate Climate Protection Programme 2022, or the increase in the price of certificates in the EU-ETS since the beginning of 2021.

Climate Action Programme 2030

Climate Action Programme 2030 enshrines the target to reduce emissions from the building sector to 72 million tonnes of CO2 per year (BReg2019). The instrument-mix will consist of: increased subsidies, CO2 pricing and regulatory measures (BReg2019). Tax deductions for energy-efficient building renovations have also been implemented. Energy-efficient renovation measures such as replacing heating systems, installing new windows, and insulating roofs and exterior walls are to receive tax incentives from 2020. Building owners of all income classes will benefit equally through a tax deduction. The funding rates of the existing KfW funding programmes were increased by 10 % (BReg2019).

The Climate Protection Programme 2030 includes 96 sectoral and cross-sectoral measures to reduce emissions. The programme does not contain target values for the GHG reduction for the individual measures (BRH 2022: 17). The programme continues some measures of the 2020 programme that have demonstrably not contributed to a GHG reduction (BRH 2022: 17).

Energy Efficiency Strategy 2050

Germany’s Energy Efficiency Strategy 2050 serves as a framework to enhance the country’s energy efficiency policies. By doing so, it aligns with the European Union’s energy efficiency target of reducing primary and final energy consumption by at least 32.5% by 2030. The strategy establishes an energy efficiency target for 2030 and consolidates the required measures in a new National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NAPE 2.0). Moreover, it provides guidelines on how the dialogue process for the Energy Efficiency Roadmap 2050 should be structured, promoting effective stakeholder engagement and collaboration.

Energy Efficiency Strategy is reported to the EU in fulfilment of Germany’s NECP requirements and Art. 7 EED. In 2023, the EU will consider whether the Europe-wide reduction targets need to be increased. There are also plans to draft a monitoring report in Germany. The report will look at whether the efficiency target for 2030 is still appropriate in view of the long-term goal of achieving greenhouse gas neutrality or whether it needs to be tightened. The Federal Agency for Energy Efficiency (BfEE) supports the BMWK in the implementation of the Roadmap Energy Efficiency 2050. The implementation of the Roadmap process is supported by a consortium around Prognos. A scientific support group appointed by the BMWK ensures the integration of the BMWK’s research platforms into the roadmap process. The administrative tasks are carried out by the German Energy Agency (dena).

National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency

The NAPE (National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency) was designed as a comprehensive set of measures aimed at improving energy efficiency in Germany. NAPE was first implemented in 2014, alongside the climate action plan 2020. NAPE 2.0, was implemented in 2019 as part of the Energy Efficiency Strategy 2050 (BMWi 2019). It incorporated policy learnings and adapts to new developments, particularly focusing on the timeframe from 2021 to 2030. NAPE 2.0 will be again updated this year in alignment with the new roadmap for energy efficiency “Energieeffizienz für eine klimaneutrale Zukunft 2045”.

NAPE has annual monitoring requirements. NAPE has been monitored annually since 2014 under the mandate of BfEE. However, the last publicly available report was published in 2021 for the reporting period of 2018-2019 (NAPE-monitoring-2021). It is unclear if this lack of publication is due to the change in government, COVID, the Ukraine conflict, or a combination of all of these factors.

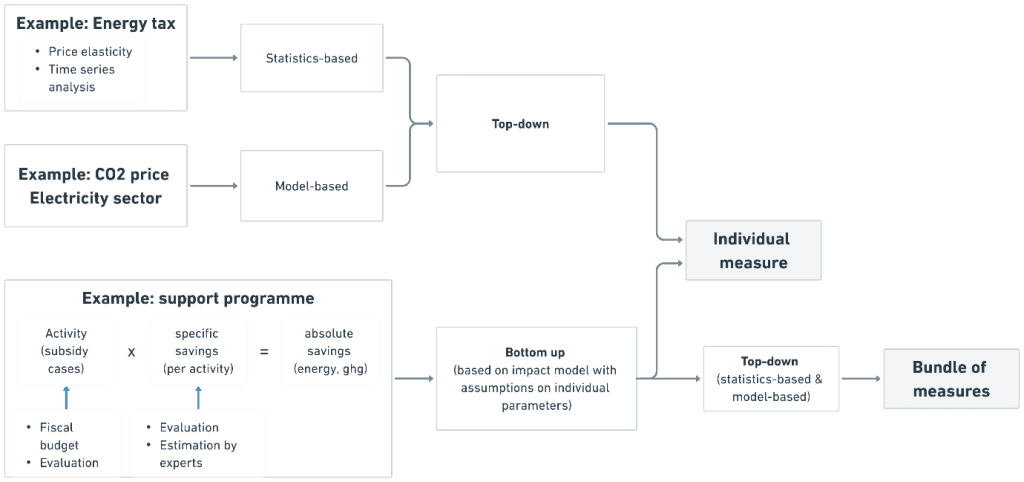

Aggregate evaluation informs the NAPE reporting. NAPE reporting is the main mechanisms for evaluation energy efficiency measures. This is a large multi-sectoral report which includes the building sector. The aggregate NAPE reporting draws from bottom-up ex-post evaluations, modelling, and statistical extrapolation.

4.1.3. Sectoral programmes

The Fuel Emissions Trading Act (BEHG)

The Fuel Emissions Trading Act (BEHG) established a carbon price mechanism for buildings and transport until 2026. BHEG incorporated all fuel emissions outside the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) into the national emissions trading system (nationalen Emissionshandel -nEHS) since 2021. From 2021 to 2025, the nEHS operates as an emissions trading system with fixed CO2 prices that increase annually, starting at 25 euros/t in 2021 and reaching 45 euros/t in 2025. From 2026 onwards, a price corridor of 55 to 65 euros/t CO2 will be implemented, however the future of the BHEG beyond 2026 remains undefined.

The BEHG has reporting requirements and revision steps every two years, starting in 2022. The Federal Government is obligated to conduct evaluations of the Act (BMUV 2021). These evaluations are required to be submitted as progress reports to the Bundestag by November 30, 2022, and November 30, 2024. Subsequently, evaluations are to be conducted every four years thereafter. The progress reports must focus on the implementation status and effectiveness of the national emissions trading scheme. They should also address the impacts of fixed prices and price corridors outlined in Section 10, Subsection (2) of the Act. Based on these findings, the government proposes necessary legal amendments to adapt and refine the emissions trading scheme. Additionally, the government is required to consider the annual climate action reports specified in Section 10 of the Federal Climate Change Act (Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz) during this process.

At the first revision step the price trajectory was paused due to gas price volatility and pressures on the costs of heating driven by trade shocks arising from the Ukraine conflict. As part of the German government’s third relief package in the beginning of 2022, the coalition committee decided to postpone the planned price increases in the nEHS by one year (at a time), starting from 2023. This decision was enacted through an amendment to the BEHG, which became effective in November 2022.

Federal Funding for Efficient Buildings (BEG)

An important building block of the Climate Action Programme 2030 is the Federal Funding for Efficient Buildings (BEG). BEG bundled the existing building funding programmes (CO2 Building Modernisation Programme, Market Incentive Programme (MAP), Energy Efficiency Incentive Programme (APEE) and Heating Optimisation Funding Programme (HZO)) commencing in 2021 in a new system that aims to meet the needs of the target groups (BMWi 2021: 92).

The BEG is structured into three sub-programmes: the BEG Residential Buildings (BEG WG), Non-residential Buildings (BEG NWG) and Individual Measures (BEG EM). For further details on the distinction between these sub-programmes see the Annex. The providers of the promotional programmes remain KfW and BAFA (Federal Office of Economics and Export Control) (section 4.2.1.).

The first formal evaluation of the BEG was recently released (06.2023). Evaluation was coordinated by Prognos, and reports on the three aggregate sub-programmes were released independently. Aggregated data and performance metrics were last published on the BEG though the BMWK website in Q3 2021 (BMWK 2021).

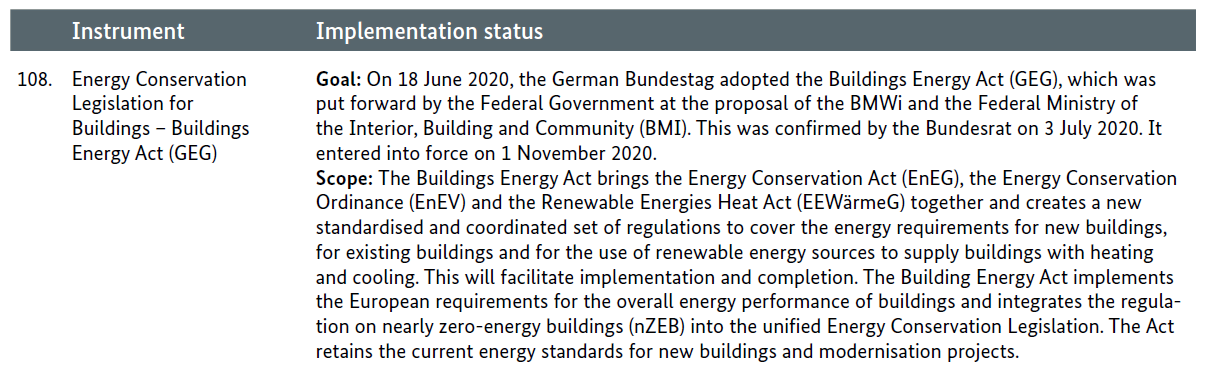

Building Energy Act (GEG)

The Building Energy Act (GEG) makes up an important building block of the Climate Protection Programme 2030. The Buildings Energy Act (GEG) entered into force on 1 November 2020 (BMWi 2021: 92) and was revised on 01.01.2023. Assessment will determine if, and to what extent, the goals of the Energy Concept will be achieved in the medium to long term. It will also help indicate what new measures need to be taken.

The GEG imposes requirements on existing buildings for retrofitting and for refurbishments. The GEG imposes retrofitting requirements for certain parts (replacement of certain old boilers, insulation of certain pipelines, insulation of top floor ceilings, installation of certain control technology of heating and air-conditioning systems) independent of measures. It also establishes standards for renovation work that would otherwise be carried out to comply with energy regulations.

The responsible authority under state law may also grant exemptions from the conditional requirements upon application. These apply in particular in the event of a lack of economic viability in an individual case. However, the guidance on how these exemptions are applied are loosely defined.

4.2. Governance and ministries