Table of Contents

Key messages

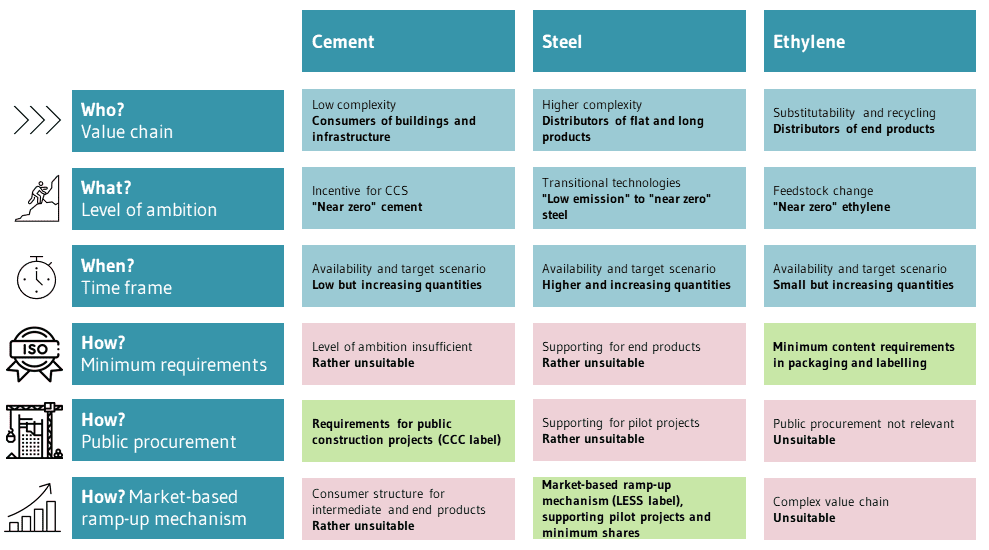

- Lead markets, in which climate-friendly basic materials are purchased despite higher costs due to their product property, can complement the existing policy mix for a competitive and climate-neutral industry. However, there are still many unanswered questions regarding the design and implementation of specific instruments for increasing demand for climate-friendly basic materials.

- Lead markets, more specifically corresponding demand-side instruments, should be designed specifically for particularly emission-intensive basic materials such as cement, steel and ethylene to effectively address the needs of the respective industry sector (see overview figure below).

- For cement, due to the homogeneous value chain structure, requirements for public construction projects based on the CCC label of the industry sector are a viable option. The German government’s special fund for infrastructure and climate neutrality could secure the financing of public construction projects.

- For steel, a European-level market-based ramp-up mechanism for distributors of flat and long products makes sense, while public procurement can provide short-term support through minimum shares and pilot projects.

- Due to various challenges, low but increasing minimum content requirements for climate-friendly ethylene in packaging are suited to the industry sector’s specific challenges – a prerequisite for this is the establishment of a climate-friendly ethylene label.

- Discussions at national and EU level should be continued on the basis of these sector-specific findings so that lead markets can fulfil their intended role in the policy mix.

1. Introduction

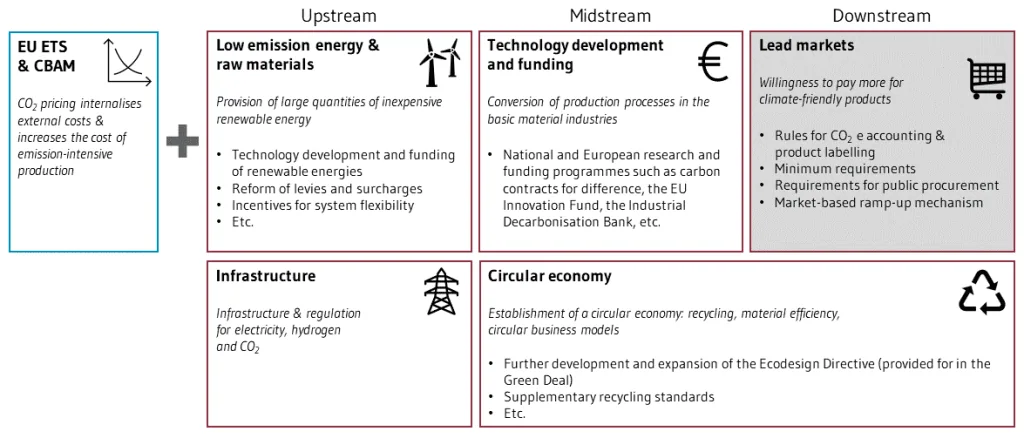

Lead markets – more specifically instruments for increasing demand for climate-friendly basic materials – can complement CO2 pricing, reduce the need for subsidies and strengthen competitiveness by ensuring that additional costs are passed on to consumers without placing a significant burden on them (see Info box: Additional costs at the end-product level). They can also support the creation of framework conditions for industrial transformation, as increased demand creates both planning certainty and investment incentives. Furthermore, lead markets address information-related externalities (Martini et al. 2024), as labelling allows to distinguish between climate-friendly and climate-damaging basic materials (BMWK 2022). As shown in the figure below, lead markets can thus contribute to a balanced policy mix on the demand side (Rogge and Schleich 2018; Peters et al. 2012).

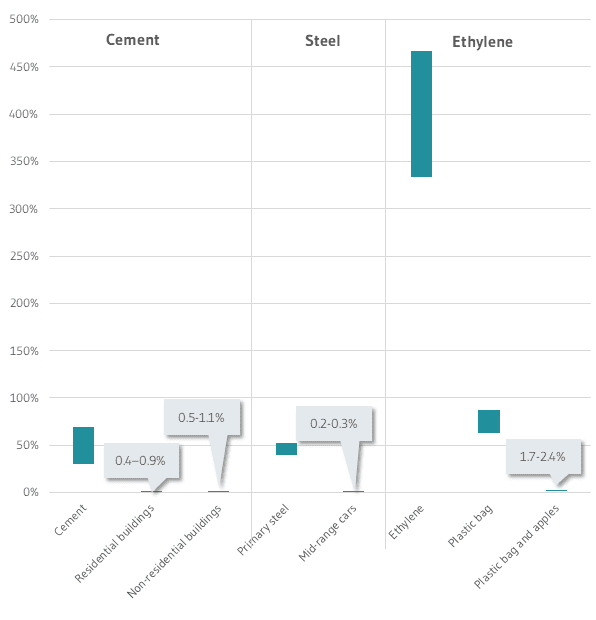

Info box: Additional costs at the end-product level

The production of climate-friendly basic materials involves additional costs compared to conventional products. These costs vary in the literature, depending, among other things, on the considered energy prices. The figure below plots these additional costs at the end-product level, assuming full cost roll-over, using Germany as an example. The additional costs at the basic material-level are significant but add very little to the cost of the end products. If additional costs can be passed on to the end products, the cost increase per product will be low, typically around 1%.

Although initial steps have been taken at both national and EU levels, there are still many unanswered questions regarding the implementation of specific instruments. The following analysis addresses these questions with implementation recommendations for lead market instruments for the particularly emission-intensive production of cement, steel and ethylene to complement the existing policy mix.

2. Lead markets for climate-friendly basic materials

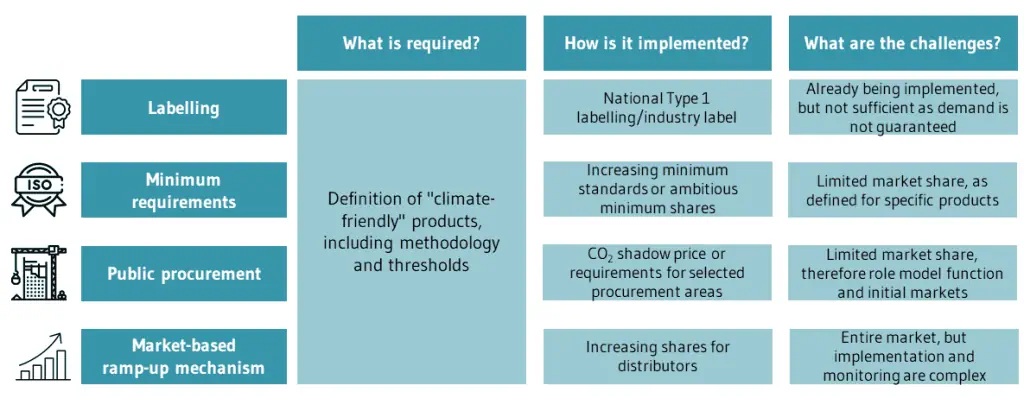

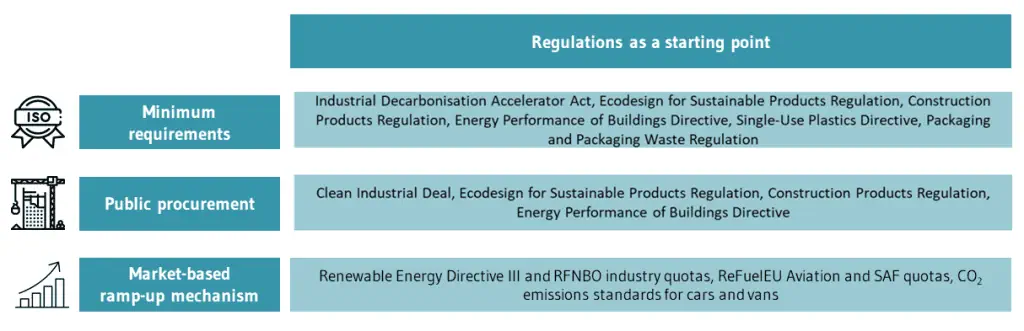

Lead markets cannot be created using a single instrument; rather, a bundle of instruments is required (see Figure 3). The first prerequisite is a uniform classification of climate-friendly basic materials, as proposed, for example, by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection in it’s concept “Lead markets for climate-friendly basic materials” (BMWK 2024). This lays the basis for four key instruments (Hannon et al. 2015), which are complementary and not mutually exclusive.

The first option is to label climate-friendly basic materials with certificates or labels. Examples of these so-called Type 1 product labels are the LESS (Low Emission Steel Standard) and CCC (Cement Carbon Class) labels established by industry associations in Germany for climate-friendly steel and cement, respectively (WV Stahl 2024; VDZ n.d.).

Another option is to have minimum requirements (standards or shares), which increase over time, for example the standards set by the Energy Consumption Labelling Regulation (2017/1369). Similarly, ambitious minimum shares can be established for selected products, as in the mandatory recycled content requirements in the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (2025/40, PPWR for short).

Public procurement can also strengthen demand for climate-friendly basic materials via a so-called CO2 shadow price, or requirements for selected procurement areas, for example the non-price criteria proposed in the Clean Industrial Deal.

A market-based ramp-up mechanism can be implemented through gradually increasing mandatory shares for climate-friendly proportions in basic materials. Comparable approaches and quotas are currently being used for the establishment of Sustainable Aviation Fuels(SAF) on the European market (2023/2405).

Some existing regulations, especially at the European level, offer a starting point for the creation of lead markets – and in some cases, this is specifically their aim – but this varies depending on the instrument. While there are starting points for minimum requirements or public procurement, for example, new regulations are necessary to introduce a market-based ramp-up mechanism at the European level. These would need to take into account such aspects as tradability, local content criteria, sanctions and flexibility options.

3. Design of lead market instruments

To establish the lead market instruments for climate-friendly cement, steel and ethylene, there are three design parameters, which will be assessed in detail (see table below).

| Leverage point | Determines at which product level/value chain stage (basic material, intermediate product or end product) requirements are defined; at the level of basic materials and intermediate products, both manufacturers and distributors can be obliged to comply, while for end products, distributors or consumers can be obliged to comply |

| Level of ambition | Consists of the recognised property and the addressed quantity share; can be adjusted by the product requirement to be met, i.e., the maximum greenhouse gas emissions per unit, and by the share that must meet this requirement |

| Time frame | Determines the point in time or period during which the level of ambition applies; not only the point in time at which it is set, but also the adjustment of the product requirement and the share over time are decisive |

Table 1: Design parameters for lead market instruments

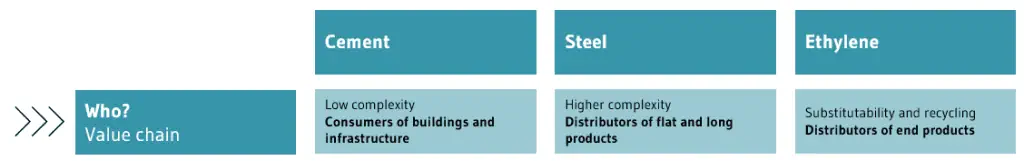

3.1. Leverage point

While requirements for basic materials provide a targeted incentive for the transformation of industry sectors, the additional costs can be passed on to consumers at subsequent stages in the value chain. It is also conceivable to incentivise further emission avoidance options for intermediate and end products, for example through the increased use of secondary products. However, focusing on this part of the value chain carries the risk that only selected products will be regulated.

Closer examination of the selected basic materials reveals a variety of industry sector characteristics, such as diversity of products and consumer markets, but also material substitution. This does not allow for a uniform statement on which stage of the value chain should be regulated.

For cement, the lower product diversity and homogeneous consumer markets mean that lead market instruments are conceivable both for distributors of the intermediate product concrete, and for distributors or consumers of the end products buildings and infrastructure. However, regulating consumers is challenging due to their high diversity.

The wide variety of steel end products, on the other hand, suggests the regulation of distributors of intermediate products, with supporting regulations for distributors of particularly relevant products, such as buildings or cars. It would be beneficial to differentiate between intermediate products based on quality differences.

In contrast to cement and steel, the production of ethylene is linked to various options for material substitution and interactions. Despite the high complexity of the consumer market, the most effective approach seems to be the regulation of distributors of selected end products – especially packaging, as the largest product segment.

3.2. Level of ambition

It is advisable to specify requirements by referring to existing proposals for climate-friendly basic materials – such as “Lead markets for climate-friendly basic materials” developed by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection (BMWK), which is based on the recommendations by the International Energy Agency (IEA) (BMWK 2024; IEA 2022). Accordingly, requirements for “low emission” and “near zero” basic materials can be specified. Requirements for “low emission” basic materials would incentivise transitional technologies towards climate-friendly basic material industries, and larger quantities of basic materials would be available earlier. On the other hand, requirements for “near zero” basic materials would secure demand for an early transition to more expensive climate-friendly production processes, with smaller quantities available. Consequently, “low emission” basic materials would need to require a higher quantity share, relative to “near zero” basic materials, to achieve a similar level of ambition.

In both options, the aim is to stimulate the necessary transformation of production routes and value chains. Looking at the three industry sectors, it becomes clear that there is no uniform conclusion, as the necessary transformation of the sectors differs fundamentally.

Since the establishment of carbon capture and storage (CCS) is necessary to achieve the target in cement production, the “near zero” definition appears to be appropriate for setting requirements. This means that the quantity addressed must be ambitious but achievable, to ensure that the requirements are met.

This contrasts with the steel sector, where the definition of “low emission” steel can also encourage a switch to new steel production processes, such as direct reduction with natural gas. In this case, the required quantity can be higher and, over time, the level of ambition can be increased by tightening the emission intensity requirement.

For ethylene, the “near zero” definition seems to be the right approach for establishing new production processes that also avoid end-of-life emissions. However, a holistic view of petrochemical production, taking into account its by-products and precursors, is necessary to counteract a one-sided maximisation of climate-friendly ethylene production.

3.3. Time frame

In the short term, the availability of climate friendly basic materials is determined by existing and planned production capacities, and the availability of the necessary infrastructure. Subsidising new production processes can increase the availability of such basic materials, but in the medium term, requirements must go beyond this to fulfil the intended role in the policy mix. A viable option is to consider on cost-efficient technology pathways, such as the technology mix scenario in the Ariadne scenario report for Germany (Luderer et al. 2025).

Here, too, no uniform conclusion emerges for all three industry sectors under consideration. An additional challenge is the inherent uncertainty of future technology pathways. The technology mix scenario is rather optimistic and envisages climate-friendly production quanities in the short term that exceed current project announcements.

For example, only a small share of “near zero” cement can realistically be considered by 2030, as CCS will be necessary and has not yet been established. In the medium term, however, this share must increase significantly to ensure that the targets are achieved by 2045.

For steel, a higher share can be addressed before 2030 due to the availability of lower emission steel production processes. However, the level of ambition must be adjusted before 2045 by tightening both the product requirements and the quantity share addressed.

For ethylene, as with cement, a relatively low share of “near zero” appears to be appropriate from 2030 onwards, as the production facilities are not yet available and will require a significant amount of renewable electricity and hydrogen. However, this share must increase significantly by 2045.

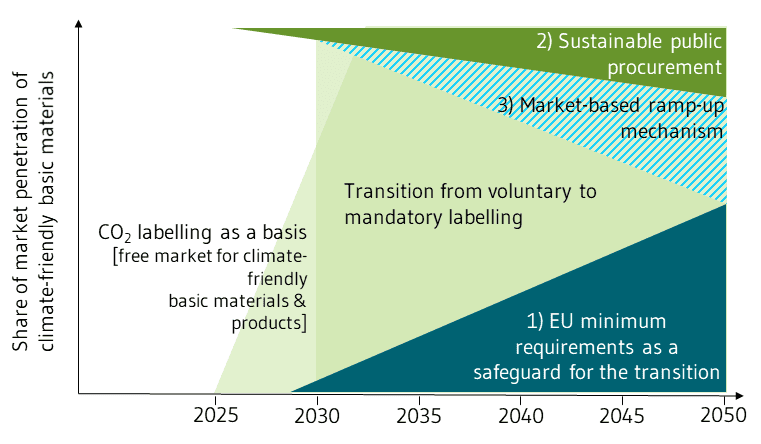

4. Implementation proposals for lead market instruments

Lead market instruments play different roles over time (see Figure 8). First, labelling is necessary to make the carbon footprint visible. Voluntary agreements are a first step, but they must subsequently become mandatory. Minimum requirements at the European level can provide short-term security, but they only offer incentives for specific product groups. In addition, public procurement can create initial markets in the short term, but these are limited in scope and their relative importance declines over time. In the medium term, a market-based ramp-up mechanism at the European level is one way of generating significant demand. Due to their complementarity, minimum requirements and public procurement can be established in parallel, but earlier than a market-based ramp-up mechanism.

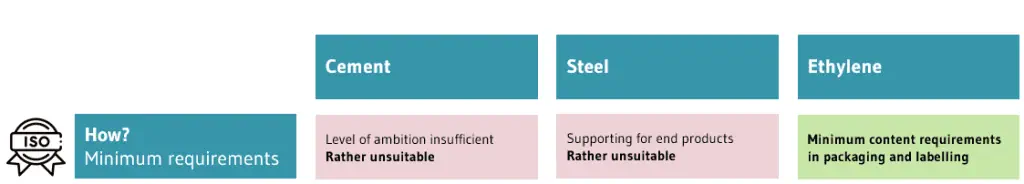

4.1. Minimum requirements for specific product groups

Minimum requirements can be implemented either through emission intensity requirement (minimum standards) or requirements on the use of certain materials (minimum shares). While the former is solution-neutral, the latter has a more direct impact on the respective basic material industries. Minimum requirements can play an important role, especially for basic materials with a complex structure of end sectors and products.

In the case of cement, it is questionable whether minimum requirements offer sufficient incentive for the transformation of the industry, as no ambitious minimum shares can be set in line with existing regulations (Construction Products Regulation, Energy Performance of Buildings Directive).

Minimum requirements for steel end products can have a supporting function in the short term. While it is possible to set ambitious minimum shares within the framework of the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation, the regulation of products is fragmented and lengthy.

Minimum requirements could create an incentive to switch from fossil feedstocks for ethylene production in the short term. Since packaging is already regulated, setting “near zero” minimum content requirements that increase over time, in line with the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation, appears promising.

4.2. Requirements in public procurement

Public procurement can be implemented via a CO2 shadow price on the one hand, and via requirements for selected procurement areas on the other. While the former is solution-neutral, the latter has a more direct effect on the respective basic material industries. It can play a decisive role in establishing lead markets, as requirements can be tested before they are widely applied.

Public procurement is particularly relevant for cement beyond the pilot phase, as the public sector is a significant consumer. In the short term, requirements could be established for the use of “near zero” cement in public construction projects, increasing over time.

Public procurement can play a supporting role for steel (e.g. buildings or cars) in the short term. This only works for the construction sector in conjunction with cement, as secondary steel is mainly used, while the automotive sector has only a weak signal effect due to low demand.

The advantages and opportunities of public procurement cannot be used effectively for ethylene, as the public sector is of little relevance for plastic packaging. There is direct demand for plastics from the public sector in the construction industry, but only small quanities of ethylene are used there.

4.3. Market-based ramp-up mechanism at the European level

The Market-based ramp-up mechanism is the instrument with the greatest potential for creating a lead market, although there are risks such as material substitution. In addition, it will require complex monitoring and appropriate certification. However, as the instrument addresses the entire market (as far as possible), it is only suitable for basic materials where the necessary processes are widely available.

The advantages of a market-based ramp-up mechanism, in terms of establishing a predictable ramp-up pathway, cannot be meaningfully applied to cement. The level of ambition required to transform the industry would be highly impractical to achieve across the board.

A market-based ramp-up mechanism for distributors, differentiated by flat and long steel and quality and structural steel, is a suitable lead market instrument, as the necessary processes for emission-reduced production are fundamentally available.

The advantages of market-based ramp-up mechanism are difficult to exploit for ethylene due to the high complexity of the value chain, the necessary level of ambition and possible diversionary movements.

5. Potential of the implementation proposals using Germany as an example

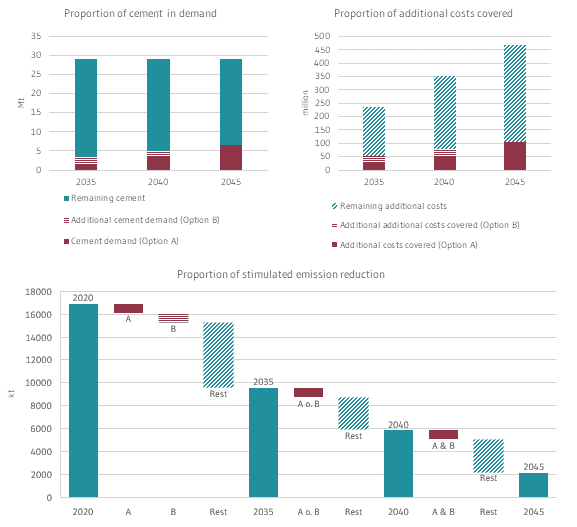

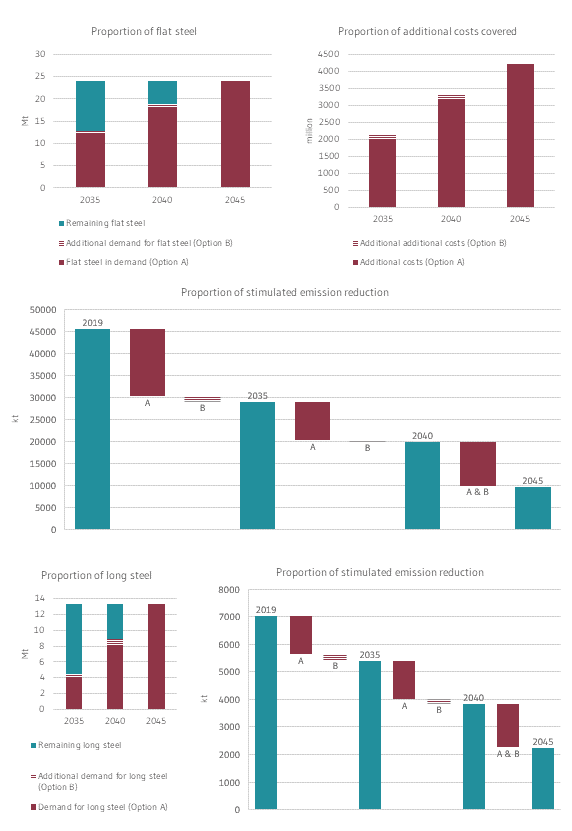

The potential of each of the implementation proposals is assessed using Germany as an example. It is assumed that the entire production of basic materials will be transformed in accordance with the Ariadne technology mix scenario (Luderer et al. 2025). Consequently, the shares of the instruments in this transformation are estimated.

5.1. Minimum shares for packaging

The figure below compares two options. Option A is less ambitious, while Option B is based on the Ariadne technology mix scenario. It is clear that, despite an incentive to transition to non-fossil feedstocks, further instruments are necessary.

5.2. Public procurement for cement

Figure 13 compares two options for cement. Option A assumes a non-linear increase in the proportion of “near zero” cement. Option B shows a linear increase. It is clear that public procurement can play a relevant role in the transformation of the cement industry, but that further instruments are necessary.

5.3 Market-based ramp-up mechanism for flat and long steel products

Figure 14 compares two options. Option A corresponds to process shares slightly below the Ariadne technology mix scenario, while option B corresponds to this scenario. It is clear that a market-based ramp-up mechanism can make a major contribution to the transformation of the steel industry.

6. Conclusions

Lead markets can complement the existing policy mix for the transformation to a competitive and climate-neutral industry, but there are still many unanswered questions regarding the design and implementation of specific instruments. When looking at the particularly emission-intensive basic materials cement, steel and ethylene, it becomes clear that lead market instruments must be developed on an industry sector-specific basis.

For cement, distributors of concrete and consumers of buildings and infrastructure are particularly well-suited to lead market instruments. Since the use of CCS is necessary, the level of ambition should initially require low but increasing quantities of “near zero” cement. Public procurement is a suitable lead market instrument in this industry sector, as the public sector demands relevant quantities of cement in construction projects. It remains to be seen how private builders can be obliged.

Lead market instruments for climate-friendly steel can be established especially for flat and long products as well as in the short term for buildings and cars as supporting measures. Lower emission production processes can also be incentivised for steel, but the quantities addressed must be higher in the short term. This lends itself to a market-based ramp-up mechanism, but this instrument would require a new regulation at the European level and detailed data to determine an appropriate ramp-up pathway. In addition, other aspects such as tradability and sanctions must be examined at the European level.

Ethylene poses particular challenges, as the high complexity of the value chain requires both a focus on end products and a change in raw materials. This makes minimum shares for “near zero” ethylene in plastic packaging a particularly suitable instrument, along with the establishment of a label for climate-friendly ethylene. It remains to be seen how lead market instruments can be established for other products in the ethylene value chain. While the foundations for establishing lead markets within the policy mix have already been laid, both at national and EU levels, these should be continued on the basis of the recommendations described here.

References

Agora Industrie; FutureCamp; Wuppertal Institut (2022): Klimaschutzverträge für die Industrietransformation: Rechner für die Abschätzung der Transformationskosten einer klimafreundlichen Zementproduktion. Version Modellversion 1.1. Berlin. Available online at https://www.agora-industrie.de/daten-tools/transformationskostenrechner-zement, last reviewed on 11/13/2024.

Agora Industrie; FutureCamp; Wuppertal Institut; Ecologic Institut (Hg.) (2021): Klimaschutzverträge für die Industrietransformation. Aktualisierte Analyse zur Stahlbranche. Available online at https://www.agora-industrie.de/publikationen/klimaschutzvertraege-fuer-die-industrietransformation-stahl, last reviewed on 11/13/2024.

BMWK (Hg.) (2022): Transformation zu einer klimaneutralen Industrie: Grüne Leitmärkte und Klimaschutzverträge. Gutachten des Wissenschaftlichen Beirats beim Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (BMWK). Berlin. Available online at https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Ministerium/Veroeffentlichung-Wissenschaftlicher-Beirat/transformation-zu-einer-klimaneutralen-industrie.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5, last reviewed on 10/21/2025.

BMWK (Hg.) (2024): Leitmärkte für klimafreundliche Grundstoffe. Berlin. Available online at https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Klimaschutz/leitmaerkte-fuer-klimafreundliche-grundstoffe.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=23, last reviewed on 07/29/2025.

Diesing, Philipp; Lopez, Gabriel; Blechinger, Philipp; Breyer, Christian (2025): From knowledge gaps to technological maturity: A comparative review of pathways to deep emission reduction for energy-intensive industries. In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 208, S. 115023. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2024.115023.

Fischer, Andreas; Küper, Malte (2021): Green Public Procurement: Potenziale einer nachhaltigen Beschaffung. Emissionsvermeidungspotenziale einer nachhaltigen öffentlichen Beschaffung am Beispiel klimafreundlicher Baumaterialien auf Basis von grünem Wasserstoff. Hg. v. Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft. Köln. Available online at https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/andreas-fischer-malte-kueper-potenziale-einer-nachhaltigen-beschaffung.html, last reviewed on 11/13/2024.

Gruhler, Karin; Deilmann, Clemens (2017): Materialaufwand von Nichtwohngebäuden. Methodisches Vorgehen, Berechnungsverfahren, Gebäudedokumentation. Teil II. Hg. v. Fraunhofer IRB Verlag. Leibniz-Institut für ökologische Raumentwicklung. Dresden.

Hannon, Matthew J.; Foxon, Timothy J.; Gale, William F. (2015): ‘Demand pull’ government policies to support Product-Service System activity: the case of Energy Service Companies (ESCos) in the UK. In: Journal of Cleaner Production 108, S. 900–915. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.082.

IEA (Hg.) (2022): Achieving Net Zero Heavy Industry Sectors in G7 Members. Available online at https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/c4d96342-f626-4aea-8dac-df1d1e567135/AchievingNetZeroHeavyIndustrySectorsinG7Members.pdf, last reviewed on 11/13/2025.

Luderer, Gunnar; Bartels, Frederike; Brown, Tom; Aulich, Clara; Benke, Falk; Fleiter, Tobias et al. (2025): Die Energiewende kosteneffizient gestalten: Szenarien zur Klimaneutralität 2045. Kopernikus-Projekt Ariadne. Hg. v. Gunnar Luderer, Frederike Bartels und Tom Brown. Potsdam. Available online at https://ariadneprojekt.de/publikation/report-szenarien-zur-klimaneutralitat-2045/, last reviewed on 03/10/2025.

Martini, Leon; Görlach, Benjamin; Kittel, Lena; Sultani, Darius; Kögel, Nora (2024): Between climate action and competitiveness: towards a coherent industrial policy in the EU. Hg. v. Ecologic Institute. Available online at https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2024/30021-Ariadne-EU-Industrial-Policy.pdf, last reviewed on 02/27/2025.

Maurer, Philipp (2013): Life Cycle-Analyse von Antriebsstrangkomponenten für den Verkehrssektor. Diplomarbeit. TU Graz, Graz. Available online at https://diglib.tugraz.at/download.php?id=576a826e727b3&location=browse, last reviewed on 11/13/2024.

Moya, J.; Boulamanti, A. (2016). Production costs from energy-intensive industries in the EU and third countries. Hg. v. JRC (Publications Office of the European Union). Available online at https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC100101, last reviewed on 07/30/2025.

Peters, Michael; Schneider, Malte; Griesshaber, Tobias; Hoffmann, Volker H. (2012): The impact of technology-push and demand-pull policies on technical change – Does the locus of policies matter? In: Research Policy 41 (8), S. 1296–1308. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.004.

Plastics Europe (Hg.) (2022): Plastics – the Facts.

Rogge, Karoline S.; Schleich, Joachim (2018): Do policy mix characteristics matter for low-carbon innovation? A survey-based exploration of renewable power generation technologies in Germany. In: Research Policy 47 (9), S. 1639–1654. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.05.011.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Hg.) (2023): Ausgewählte Zahlen für die Bauwirtschaft. Available online at https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Bauen/Publikationen/Downloads-Querschnitt/bauwirtschaft-1020210221124.pdf?__blob=publicationFile, last reviewed on 08/04/2025.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Hg.) (2025): Auftragseingang, Geleistete Arbeitsstunden, Baugewerblicher Umsatz im Bauhauptgewerbe (Betriebe mit 20 u.m. tätigen Personen): Bundesländer, Monate, Bauarten. Available online at https://www-genesis.destatis.de/datenbank/online/url/0ad07d3e, zuletzt aktualisiert am 25.07.2025, last reviewed on 08/04/2025.

VDZ (Hg.) (o.J.): CO2-Label für Zement. Available online at https://www.vdz-online.de/leistungen/zertifizierung/co2-label-fuer-zement-ccc-zertifizierung, last reviewed on 07/30/2025.

VDZ (Hg.) (2021): Zementindustrie im Überblick 2021/2022. Available online at https://vdz.info/ziue21, last reviewed on 11/12/2024.

World Steel Association (Hg.) (2022): Steel Statistical Yearbook 1978-2019. Available online at https://worldsteel.org/steel-by-topic/statistics/steel-statistical-yearbook/, last reviewed on 02/22/2022.

Wurzer, Andreas (2016): Bewertung möglicher gesetzlicher Lenkungseffekte auf Basis gesamtheitlicher Lebenszyklusanalysen im Verkehrssektor. Masterarbeit. TU Graz. Available online at https://diglib.tugraz.at/download.php?id=5891c8377cd82&location=browse, last reviewed on 11/13/2024.

WV Stahl (Hg.) (2024): Introduction of a Low Emission Steel Standard (LESS) to support the transformation of the steel industry. Available online at https://www.wvstahl.de/wp-content/uploads/20240422_concept-paper_LESS_final.pdf, last reviewed on 30.07.2025.

Zottler, Michael (2014): Life-Cycle Analyse von Leichtbaukonzepten für den Automobilbau. Diplomarbeit. TU Graz, Graz. Available online at https://diglib.tugraz.at/download.php?id=576a7fd6970b7&location=browse, last reviewed on 11/13/2024.